DIE BEFORE DYING

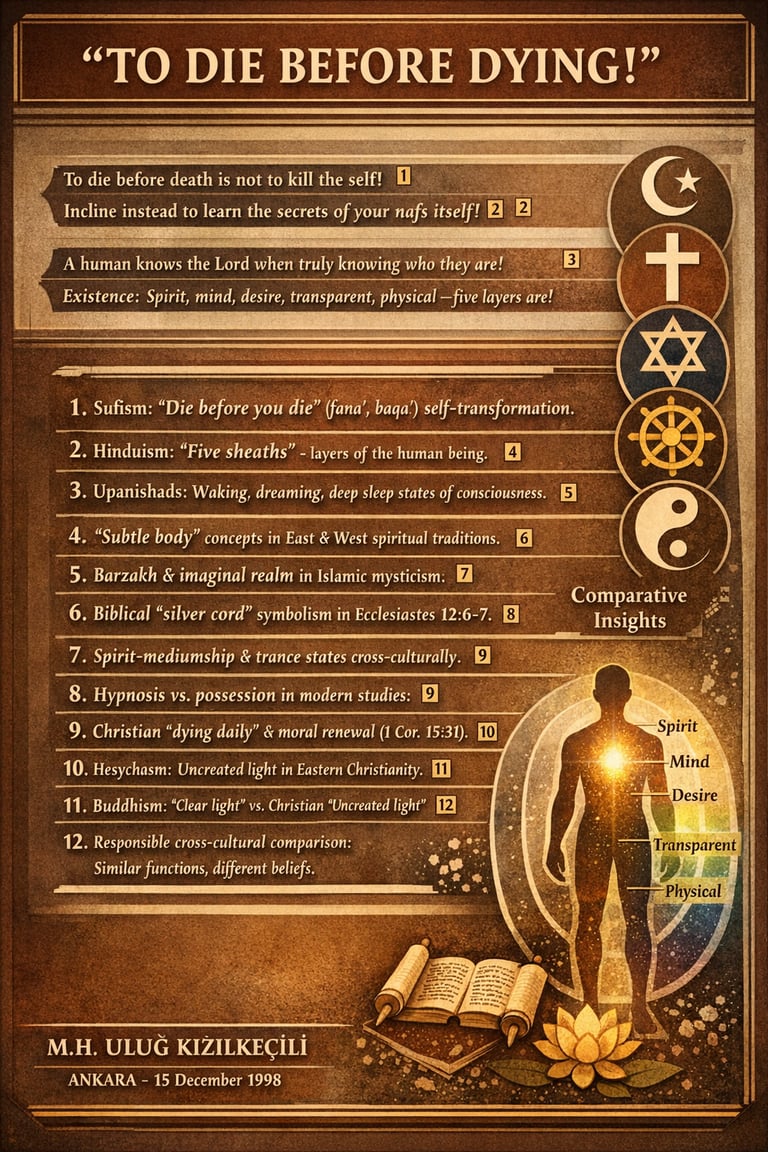

DIE BEFORE DYING. To die before death is not to kill the self! Incline instead to learn the secrets of your nafs itself! A human knows the Lord when truly knowing who they are! Existence: Spirit, mind, desire, transparent, physical — five layers are!

APOCALYPSE BOOK

DIE BEFORE DYING

To die before death is not to kill the self!

Incline instead to learn the secrets of your nafs itself!

A human knows the Lord when truly knowing who they are!

Existence: Spirit, mind, desire, transparent, physical — five layers are!

Five consciousnesses exist: Lord, human, animal, plant and earth!

Descent is the fall from Heaven; ascent is mi‘raj — a clarified heart gives birth!

The transparent body is the essence of our physical frame!

Five senses and memory dwell there; not the organs made of flesh the same!

The physical is bound to the transparent by a cord’s tie!

Its knot lies in the heart’s first cell — remember it, keep it nigh!

Through the transparent form the heart is carried before death!

For the physical body is but a spare part beneath!

Beneath the transparent layer lie the original organs’ art!

Above dwell senses and memory; the soul understands each part!

We see no dreams in deep sleep — but why is this so?

Because the soul cannot depart with the upper transparent flow!

Mediumship, hypnosis, sleep, coma, trance and death’s domain!

States belonging to the transparent body — again and again!

A jinn calls it “Spirit!” and uses the medium’s subtle skin!

The hypnotist expels that form and inserts his antenna within!

He places his own transparent body into your brain’s domain!

You obey every command; your free will suffers pain!

When you awaken you know not you even slept awhile!

Yet the medium remembers — therein lies the style!

No awareness exists in coma nor anesthesia’s deep tide!

The cord remains attached, yet the transparent body travels wide!

When the cord breaks from the heart, only a corpse remains!

The desire-body takes all records the transparent body contains!

No one can return the “lower transparent” into the dead!

Few know the difference between trance and death instead!

When ‘Isa revived, he said, “He did not die — he sleeps!”

The holy father raised the one he placed in trance’s deeps!

In trance the soul departs with the upper transparent form!

To witness the Hereafter — the greatest triumph born!

The cord never breaks from Fuad; it stretches, made of light!

The soul rides the transparent steed, accustomed to its flight!

A Lord’s Saint may ascend with the upper transparent frame!

Condensing it, even “lies with Maryam,” so claim!

The Torah says: “Ibrahim and Jibril shared a meal!”

“Yahweh wrestled Ya‘qub one night,” the scriptures reveal!

“When He lost the struggle, at dawn Mikail appeared!”

“He gave Ya‘qub a new name — Israel,” revered!

Israel means “one who wrestles with the Lord” in might!

Strive to rise toward the Lord’s vibration and light!

Ibrahim addresses Mikail as “Rab,” so the stories say!

“If ten righteous exist, spare Lut’s people today!”

Do not say Azrail takes the souls of saints away!

Azrail too is an angel — “He prostrated to Adam,” they say!

The saint cuts the cord from his own heart’s decree!

“The martyr dies,” and becomes the master of the Throne — free!

Master M.H. Ulug Kizilkecili

Türkiye/Ankara - 15 December 1998

IMPORTANT NOTE :The original text is poetic, and the author cannot be held responsible for any errors in the English translation! To read the original Turkish text, click HERE! The following section is not the author's work, and the author cannot be held responsible for any errors made!

English Footnotes (comparative, academically expanded)

“To die before dying” (Islamic mysticism / Sufism): In many Sufi lineages, “dying before death” is read as fanāʾ (the “passing away” of egoic qualities) followed by baqāʾ (subsistence in/through the Divine)—a transformation of consciousness and character rather than literal self-destruction. A concise academic definition and history of this pair is given in Encyclopædia Iranica under Baqāʾ wa Fanāʾ.

Ethical-ascetic emphasis (not “annihilation of the soul”): Modern academic discussions stress that Sufi “death before death” usually signifies disciplined moral/psychological change (an “art of existence”), not the claim that the lower self can be literally eliminated as an entity.

Early Sufism and the “self” vocabulary: Historical scholarship situates these themes in early Baghdadi Sufism (e.g., al-Junayd) and later metaphysical elaborations; this helps interpret the poem’s insistence that the goal is knowledge of the self’s “secrets” rather than crude self-hatred.

“Five layers” and pan-religious “stratified person” models: The poem’s layered anthropology (“spirit–mind–desire–transparent–physical”) resembles cross-cultural “multi-layer personhood” schemes. A well-known Indic parallel is the pañcakosha (“five sheaths”) model from the Upanishadic/Vedāntic tradition, in which the physical sheath is only the outermost layer.

Upanishadic consciousness-states and the sleep/dream discussion: The poem’s deep-sleep/dream motif can be compared to the Mandūkya Upanishad’s analysis of waking, dreaming, deep sleep, and a “fourth” (turiya) beyond them—often treated as a key text for comparative work on consciousness in South Asian traditions.

“Transparent body” and the comparative category of the “subtle body”: In the comparative study of religion, “subtle body” often designates a quasi-material intermediary between mind/soul and flesh, appearing across historical and cultural contexts (with very different doctrinal meanings). A major modern scholarly synthesis is Simon Cox’s The Subtle Body: A Genealogy (Oxford), which traces how “subtle body” ideas travel and mutate in late antique, medieval, Renaissance, and modern Western esoteric settings.

Asian–Western comparisons of “subtle-body practices”: For systematic cross-cultural comparison (South Asia, Tibet/East Asia, and modern Western contexts), see the edited academic volume Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West (Routledge), which frames subtle-body practices as an “in-between” anthropology used in ritual, healing, and contemplative techniques.

Islamic “imaginal/intermediate world” as a bridge concept: The poem’s “transparent” realm can be compared (carefully, not equated) with Islamic philosophical-mystical discussions of barzakh and the “imaginal” (ʿālam al-mithāl) as an intermediate mode of reality and experience—especially in Ibn ʿArabī reception. Scholarly treatment of Ibn ʿArabī’s barzakh/imagination provides a conceptual map for such readings.

Corbin and the “spiritual body” (Islam/Iran, late antique continuities): Henry Corbin’s classic Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth is a key academic reference for “subtle/spiritual body” language in Iranian and Islamic theosophical traditions, relating visionary experience, cosmology, and personhood (including imaginal embodiment).

“Cord” imagery and Hebrew Bible resonances: The poem’s “cord breaks → only corpse remains” strongly echoes Ecclesiastes 12:6–7 (“before the silver cord is snapped… and the dust returns to the earth… and the spirit returns to God”). This is an important intertext for any Abrahamic comparative commentary on “life-bond” symbolism.

Competing readings of the “silver cord”: Biblical commentary traditions vary between (a) anatomical/physiological allegories (e.g., spinal cord/brain vessels) and (b) more general metaphors for life’s precious fragility—useful when evaluating whether the poem’s “cord” should be read metaphysically, symbolically, or both.

Possession/mediumship as a cross-cultural phenomenon (anthropology of religion): The poem’s “mediumship/hypnosis/trance” claims belong to a very broad global family of “possession-trance” narratives. I. M. Lewis’s Ecstatic Religion is a major comparative anthropological study, treating possession/shamanism across societies and emphasizing psychological + sociocultural functions rather than adjudicating metaphysical truth-claims.

Altered states, social context, and typologies: Erika Bourguignon’s edited volume Religion, Altered States of Consciousness, and Social Change is a foundational academic reference for linking trance/possession to social settings and cultural models of the person (again, analytically rather than devotionally).

“Hypnosis” vs. “possession” (analytic caution): Modern scholarship typically distinguishes hypnosis (a set of suggestibility/attention practices in modern clinical/performative contexts) from “possession” (ritualized explanatory frames in religious systems), even when experiential descriptions overlap; this matters when reading the poem’s strong causal claims as theological-interpretive rather than clinically established mechanisms. (Use Lewis/Bourguignon as the comparative baseline.)

Christian parallels: “dying daily” and moral transformation: In Pauline Christianity, “I die every day” (1 Cor 15:31) and “old self/new self” language ground an ascetic-moral transformation schema that can be compared structurally (not doctrinally identical) to Sufi “death before death” discourse.

Hesychasm and the “light” tradition (Eastern Christianity): The poem’s “ascent/clarity/light” motifs can be compared with Byzantine hesychasm and Gregory Palamas’s theology of divine “energies” and the experience of “uncreated light” (often linked to the Transfiguration). Recent and accessible academic discussions summarize this “light” anthropology and its theosis framework.

Buddhist “clear light” vs. Christian “uncreated light” (comparative mysticism): Comparative scholarship has explicitly contrasted Tibetan Buddhist “clear light” experiences and Byzantine hesychast “uncreated light,” showing both experiential analogies and doctrinal divergences (e.g., views of selfhood, grace, metaphysics). This provides a rigorous template for cross-tradition “light” comparisons without collapsing differences.

Method note (how to compare responsibly): Because “subtle body / ascent / trance / light” vocabularies appear widely, responsible comparison separates (a) functional similarity (what the model does in practice: ethics, healing, contemplation, authority) from (b) ontological claim (what the tradition asserts is реально there). “Subtle body” scholarship explicitly warns that apparent universality can mask deep historical and philosophical differences.