THE MENTAL BODY , PART-3

THE MENTAL BODY , PART-3. [1] The Physical Life: [2] The Emotional Life: [3] The Mental Life [1] The Physical Life In the Astral Body, Chapter VIII, the factors in the physical life which affect the astral body were enumerated and described. Most of what was written there applies...

GİZLİ ÖĞRETİLER

THE MENTAL BODY , PART-3

CHAPTER XI

THOUGHT – TRANSFERENCE [CONSCIOUS] AND MENTAL HEALING

It is within the power of almost any two persons, provided they care to devote to the effort sufficient time and perseverance, and are capable of clear and steady thought, to convince themselves of the possibility of thought-transference, and even to become moderately proficient in the art. There is, of course, quite a considerable literature on the subject, such as the Transaction of the Psychical Research Society.

The two experiments should agree on a time mutually convenient, devoting say, ten or fifteen minutes daily to the task. Each should then secure himself from interruption of any kind. One should be the thought-projector or transmitter, and the other the receiver; in most cases it is desirable to alternate these roles in order to avoid the risk of one becoming abnormally passive; moreover, it may be found that one is much better at transmitting, the other at receiving.

The transmitter should select a thought, which may be anything from an abstract idea to a concrete object or a simple geometrical figure, concentrate on it, and will to impress it on his friend. It should scarcely be necessary to insist that the mind should be wholly concentrated, being in the condition graphically described by Patanjali as "one pointed". It is well for the inexperienced not to attempt to concentrate for too long lest the attention waver or wander, and a bad habit thus be set up, or strain develop, leading to fatigue. For many, if not for most, seconds are safer than minutes.

The receiver, making his body as comfortable as possible, least any slight bodily uneasiness serve to distract his attention from the matter in hand, must render his mind a blank –a task by no means easy to the inexperienced, but simple enough once the "knack" of it is acquired –and to note the thoughts that drift into it. These he should write down as they appear, his only care being to remain passive, to reject nothing, to encourage nothing.

The transmitter should of course, also keep a record of the thoughts which he sends, and the two records should at suitable intervals be compared.

Unless the experimenters are abnormally deficient in the use of the will and the control of thought, some power of communication will be established in a few weeks or months at latest.

The present writer [A.E.P] has known it happen at the first attempt The student of "white" occultism, once he has satisfied himself of the possibility of thoughttransference, will not be content either with academic experiments such as have been described above, or with merely sending out kind thoughts to his friends, useful as these may be in their own measure. It is possible for him to use his powers of thought to far greater effect.

Thus to take an obvious example, suppose the student wishes to help a man who is under the sway of an injurious habit such as drink. He should first ascertain at what hours the patient's mind is likely to be unemployed –such as his hour for going to bed. If the man should be asleep so much the better.

At such a time he should sit down alone and picture his patient as seated in front of him. Very clear picturing is not essential, but the process is rendered more effective if the image can be pictures vividly, clearly and in detail.

If the patient is asleep he will be drawn to the person thinking of him, and will animate the image of himself that has been formed.

The student should then, with full concentration of mind, fix his attention on the image and address to it the thoughts which he wishes to impress on his patient's mind. He should present these as clear mental images just as he would do if laying arguments before him or pleading with him in words.

Care must be taken not to attempt to control in any way the patient's will; the effort should be solely to place before his mind the ideas which, appealing to his intelligence and his emotions, may help him to form a right judgement and to make an effort to carry it out in action.

If an attempt is made to impose upon him a particular line of conduct, and the attempt succeed, even then little, if anything has been gained. For, in the first place, the weakening effect of the compulsion on his mind may do him more harm than the wrong-doing from which he has been saved. In the second place the mental tendency towards vicious self-indulgence will not be changed by opposing an obstacle in the way of indulging in a particular form of it.

Checked in one direction, it will find another, and a new vice will supplant the old. Thus a man forcibly constrained to be temperate by the domination of his will is no more cured of the vice than if he were locked up in prison.

Apart from this practical consideration, it is entirely wrong in principle, for a man to try to impose his will on another, even in order to make him do it right. True growth is not helped by external coercion ; the intelligence must be convinced, the emotions aroused and purified, before real gain is made.

If the student wishes to give any other kind of help by his thought, he should proceed in a similar way. As we saw in Chapter VIII, a strong wish for a friend's good, sent to him as a general protective agency, will remain about him as a thought-form for a time proportional to the strength of the thought, and will guard him against evil, acting as a barrier against hostile thoughts, and even warding off physical dangers. A thought of peace and consolation similarly sent will soothe and calm the mind, spreading around its object an atmosphere of calm.

It is thus apparent that thought-transference is closely associated with mind-cure, which aims at transferring good, strong thoughts from the operator to the patient. Examples of this are Christian Science, mental science, mind-healing etc. In those methods where an attempt is made to cure a man simply by believing he is well, a considerable amount of hypnotic influence is frequently exercised. The mental, astral, and etheric bodies of man are so closely connected that if a man mentally believes himself, well, his mind may be able to force his body into harmony with his mental state and thus produce a cure.

H. P. Blavatsky considered it legitimate and even wise to use hypnotism to lift a person out of drunkenness, for example, provided the operator knew enough to be able to break the habit and free the will of the patient so that it might set itself against the vice of drunkenness. The will-power of the patient having become paralysed by his addiction to drinking, the hypnotist uses the force of hypnotism as a temporary expedient to enable the man's will to recover and re-assert itself.

Nervous diseases yield the most readily to the power of the will because the nervous system has been shaped for the expression of spiritual powers on the physical plane. The most rapid results are obtained when the sympathetic system is first worked upon because that system is the most directly related to the aspect of will in the form of desire, the cerebrospinal system being more directly related to the aspect of cognition and of pure will.

Another method of healing requires the healer first to discover accurately what is wrong, to picture to himself the diseased organ, and then to image it as it ought to be. Into the mental thought-form he has thus created he next builds astral matter, and then by the force of magnetism he further densifies it by etheric matter, finally building in the denser materials of gases, liquids and solids, using the materials available in the body and supplying from outside any deficiencies.

It is obvious that this method demands at least some idea of anatomy and physiology; nevertheless, in the case of an advanced stage of evolution, the will of an operator who may be lacking in knowledge in his physical consciousness may be guided from a higher plane.

In cures effected by this method there is not the same danger that accompanies those wrought by the easier, and therefore more common, method of working on the sympathetic system alluded to above.

There is, however, a certain danger in healing by the power of will viz., the danger of driving the disease into a higher vehicle. Disease being often the final working out of evil that existed previously on the higher planes, it is better to let it work itself out than forcibly to check it and throw it back into the subtler vehicle. If it be the result of evil desire or thought, then physical means of cure are preferable to mental, because the physical means cannot cast the trouble back into the higher plane, as could happen if mental means were employed. Hence mesmerism is a suitable process, this being physical [see The Etheric Double Chapter XVIII].

A true method of healing is to render the astral and mental bodies perfectly harmonious; but this method is far more difficult and not as rapid as the will method. Purity of emotion and mind means physical health, and a person whose mind is perfectly pure and balanced will not generate fresh bodily disease, though he may have some unexhausted karma to work off –or he may even take on himself some of the disharmonies caused by others.

There are, of course, other methods of using the power of thought to heal, for the mind is the one great creative power in the universe, divine in the universe, human in man; and as the mind can create so can it restore; where there is injury the mind can turn its forces to the healing of the injury. In passing we may note also that the power of "glamour" [vide The Astral Body] is simply that of making a clear strong image and then projecting it into the mind of another.

The aid which is often rendered to another by prayer is largely of the character just described, the frequent effectiveness of prayer compared with that of ordinary good wishes being attributable to the greater concentration and intensity thrown by the pious believer into his prayer. Similar concentration and intensity without the use of prayer would bring about similar results. The student will bear in mind that we are speaking here of the effects of prayer brought about by the power of the thought of the one who prays. There are of course other results of prayer, due to a call on the attention of some evolved human, super-human, or even nonhuman intelligence, which may result in direct aid being rendered by a power superior to any possessed by the one who offers the prayer. With this type of "answers to prayer", however, we are not here immediately concerned.

All that can be done by thought for the living can be done even more easily for the "dead". As was explained in The Astral Body the tendency of a man after death is to turn his attention inwards, and to live in the feelings and mind rather than in the external world. The rearrangement of the astral body by the Desire- Elemental further tends to shut in the mental energies and to prevent their outer expression.

But the person thus checked as to his outward-going energies becomes all the more receptive of influences from the mental world, and can, therefore, be helped, cheered, and counseled far more effectively than when he was on earth.

In the world of the after-death life, a loving thought is palpable to the senses as is here a loving word or tender caress. Everyone who passes over should therefore, be followed by thoughts of love and peace, by aspirations for his swift passage onwards. Only too many remain in the intermediate state longer than they otherwise should because they have not friends who know how to help them from this side of death.

The occultists who founded the great religions were not unmindful of the service due from those left on earth to those who had passed onwards. Hence the Hindu has his Shraddha, the Christian his Masses and prayers for the "dead".

Similarly, it is possible for thought-transference to take place in the reverse direction. i.e.,, from the disembodied to those physically alive. Thus, for example, the strong thought of a lecturer on a particular subject may attract the attention of disembodied entities interested in that subject; an audience, in fact, often contains a greater number of people in astral than in physical bodies.

Sometimes one of these visitors may know more of the subject than the lecturer, in which case he may assist by suggestions or illustrations. If the lecturer is clairvoyant he may see his assistant and the new ideas will be materialised in subtler matter before him. If he is not clairvoyant, the helper will probably impress the ideas upon the lecturer's brain, and in such a case the lecturer may well suppose them to be his own.

This kind of assistance is often afforded by an "invisible helper" [vide The Astral Body,p.245-6]. The power of the combined thought of a group of people used deliberately to a certain end is well known, both to occultists and to others who know something of the deeper science of the mind. Thus in certain parts of Christendom it is the custom to preface the sending of a mission to evangelise some special district by definite and sustained thinking. In this way a thoughtatmosphere is created in the district highly favourable to the spread of the teachings thought about, and receptive brains are prepared for the instruction which is to be offered to them.

The contemplative orders of the Roman Catholic Church do much good and useful work by thought, as do the recluses of the Hindu and Buddhist faiths.

Where in fact, a good and pure intelligence sets itself to work to aid the world by diffusing through it noble and lofty thoughts, there definite service is done to man, and the lonely thinker becomes one of the lifters of the world.

Another example, which we may class as partly conscious and partly unconscious, of the way in which the thought atmosphere of one man can powerfully affect another man, is that of the association of a pupil or disciple with a spiritual teacher or guru.

This is well understood in the East, where it is recognised that the most important and effective part of the training of a disciple is that he shall live constantly in the presence of his teacher and bathe in his aura. The various vehicles of the teacher are all vibrating with a steady and powerful swing at rates both higher and more regular than any which the pupil can maintain, though he may sometimes reach them for a few moments. But the constant pressure of the stronger thought-waves of the teacher gradually raise those of the pupil into the same key. A rough analogy may be taken from musical training. A person who has yet but little musical ear finds it difficult to sing correct intervals alone, but if he joins with another stronger voice which is already perfectly trained his task becomes easier.

The important point is that the dominant note of the teacher is always sounding so that its action is affecting the pupil night and day without the need of any special thought on the part of either of them. Thus it becomes much easier for the growth of the subtle vehicles of the pupils to take place in the right direction.

No ordinary man, acting automatically and without intention, can exercise even one-hundredth part of the carefully directed influence of a spiritual teacher. But numbers may to some extent compensate for lack of individual power, so that the ceaseless though unnoticed pressure exercised upon us by the opinions and feelings of our associates leads us frequently to absorb, without knowing it, many of their prejudices, as we saw in the preceding chapter, when dealing with racial and national thought-influence.

An "accepted" pupil of a Master is so closely in touch with the Master's thought that he can train himself at any time to see what that thought is upon any given subject; in that way he is often saved from error. The Master can at any time send a thought through the pupil either as a suggestion or a message. If for example, the pupil is writing a letter or giving a lecture, the Master is subconsciously aware of the fact, and may at any moment throw into the mind of the pupil a sentence to be included in the letter or used in the lecture. In earlier stages the pupil is often unaware of this, and supposes the ideas to have arisen spontaneously in his own mind, but he very soon learns to recognise the thought of the Master. In fact, it is most desirable that he should learn to recognise it because there are many entities on the mental and astral planes who, with the best intentions and in the most friendly way, are very ready to make similar suggestions, and it is clearly necessary that the pupil should learn to distinguish from whom they come.

CHAPTER XIII

THOUGHT CENTRES

There are in the mental world certain definitely localised thought-centres, actual places in space, to which thoughts of the same type are drawn by the similitude of their vibrations, just as men who speak the same language are drawn together. Thoughts on a given subject gravitate to one of these centres, which absorbs any number of ideas, coherent or incoherent, right or wrong, the centre being a kind of focus for all the converging lines of thought about that subject, these again, being linked by millions of lines with all sorts of other subjects.

Philosophical thought, for example, has a distinct realm of its own with sub-divisions corresponding to the chief philosophical ideas; all sorts of curious inter-relations exist between these various centres, exhibiting the way in which different systems of philosophy have linked themselves together. Such collections of ideas represent all that has been thought upon that subject.

Anyone who thinks deeply, say on philosophy, brings himself in touch with this group of vortices. If he is in his mental body, whether he be asleep or "dead", he is drawn spatially to the appropriate part of the mental plane. If the physical body to which he may be attached prevents this, he will rise into a condition of sympathetic vibration with one or other of these vortices, and will receive from them whatever he is capable of assimilating; but this process will be some-what less free than would be the case if he had actually drifted into it.

There is not precisely a thought-centre for drama and fiction, but there is a region for what may be called romantic thought –a vast, but rather ill-defined group of forms, including on one side a host of vague but brilliant combinations connected with the relation of the sexes, on another the emotions characteristic of mediaeval chivalry, and on yet another masses of fairy stories.

The influence of thought-centres on people is one of the reasons why people think in droves like sheep; for it is much easier for a man of lazy mentality to accept a ready-made thought from someone else than to go through the mental labour of considering a subject and arriving at a decision for himself. The corresponding phenomenon in the astral world works in a slightly different manner. Emotion-forms do not all fly up to one world-centre, but they do coalesce with other forms of the same nature in their own neighbourhood, so that enormous and very powerful "blocks" of feeling are floating about almost everywhere, and a man may very readily come into contact with them and be influenced by them. Examples of such influence occur in cases of panic, maniacal fury, melancholia, etc. Such undesirable currents of emotion reach a man through the umbilical chakram. In a similar manner a man may be beneficially affected by noble emotions operating through the heart chakram.

It is difficult to describe the appearance of these reservoirs of thought; each thought appears to make a track, burrowing a way for itself through the matter of the plane. That way, once established, remains open, or rather may readily be re-opened, and its particles re-vivified by any fresh effort. If this effort be at all in the general direction of the first line of thought it is far easier for it to adapt itself sufficiently to pass along that line that it is for it to hew out for itself a slightly different line, however closely parallel that may be to the one which already exists.

The content of these thought-centres is, of course, far more than enough for any ordinary thinker to draw upon. For those who are sufficiently strong and persevering there are yet other possibilities connected with these centres.

First: It is possible through these thought-centres to reach the minds of those who generated their force. Hence one who is strong, eager, reverent, and teachable, may actually sit at the feet of great thinkers of the past and learn from them of the problems of life . A man is thus able to psychometrise the different thought-forms in a thought-centre, follow them to their thinkers, with whom they are connected by vibration, and acquire other information from them.

Second : There is such a thing as the Truth in itself, or, if that idea is too abstract to be grasped, we may say it is the conception of that Truth in the mind of our Solar Logos. That thought can be contacted by one who has attained conscious union with the deity, but by no one below that level. Nevertheless, reflections of it are to be seen, cast from plane to plane, growing ever dimmer as they descend. Some at least of these reflections are within reach of a man whose thought can soar up to meet them.

From the existence of these thought-centres follows another point of considerable interest. It is obvious that many thinkers may be drawn simultaneously to the same mental region, and may gather there exactly the same ideas. When that happens it is possible also that their expression of those ideas in the physical world may coincide; then they may be accused by the ignorant of plagiarism. That this does not happen more frequently than actually is the case is due to the density of men's brains, which comparatively rarely bring anything learned on higher planes.

This phenomena happens not only in the field of literature, but also in that of inventions, for it is well known in Patent Offices that practically identical inventions often arrive simultaneously.

Other ideas may be obtained by writers from the akashic records; but this aspect of our subject will be dealt with in a later chapter.

CHAPTER XIII

PHYSICAL OR "WAKING" CONSCIOUSNESS

In this chapter we shall consider the mental body as it exists and is used during ordinary "waking" consciousness, i.e.,, in ordinary physical life. It will be convenient to deal seriatim with the three factors which determine the nature and functioning of the mental body in physical life, viz.:

[1] The Physical Life:

[2] The Emotional Life:

[3] The Mental Life

[1] The Physical Life

In the Astral Body, Chapter VIII, the factors in the physical life which affect the astral body were enumerated and described. Most of what was written there applies, mutatis mutandis, to the mental body. We shall here, therefore not deal again at any length with those factors, but merely briefly recapitulate them, with a minimum of comment where necessary.

As every part of the physical body has its corresponding astral and mental counterparts, it follows that a coarse and impure physical body will tend to make the mental body also coarse and impure. In view of the fact that the seven grades of mental matter correspond respectively to the seven grades of physical [as well, of course, as to those of astral] matter, it would seem that the mental body would be more especially affected by the physical solids, liquids, gases, and ethers, i.e.,, by the four orders of physical matter.

It will, of course be clear to the student that a mental body composed of the coarse varieties of mental matter will respond to the coarser types of thought more readily than to the finer varieties.

Coarse food and drink tend to produce a coarse mental body. Flesh foods, alcohol, tobacco are harmful to the physical, astral and mental bodies. The same applies to nearly all drugs.

Where a drug, such as opium, is taken in order to relieve great pain, it should be taken as sparingly as possible. One who knows how to do it can remove the evil effect of opium from the mental and astral bodies after it has done its work upon the physical.

Furthermore, a body fed on flesh and alcohol is especially liable to be thrown out of health by the opening up of the higher consciousness; nervous diseases, in fact partly due to the fact that the higher consciousness is trying to express itself through bodies clogged with flesh products and poisoned by alcohol.

Dirt of all kinds is often objectionable in the higher worlds than in the physical. Thus for example, the mental and astral counterparts of the waste matter which is constantly being thrown off by the physical body as invisible perspiration are of the most undesirable character.

Loud, sharp or sudden noises should, as far as possible, be avoided by anyone who wishes to keep his astral and mental bodies in order. This is one of the reasons why the life of a busy city is one to be avoided by an occult student, as well as by children upon whose plastic astral and mental bodies the effects of ceaseless noise are disastrous. The cumulative effect of noise on the mental body is a feeling of fatigue and inability to think clearly.

A man's mental body is affected by almost everything in his environment. Thus for example, the pictures which hang on the walls of his rooms influence him, not only because they keep before his eyes the expression of certain ideas, but also because the artist puts a great deal of himself, of his inmost thought and feeling, into his work. This we term the unseen counterparts of the picture, clearly expressed in mental and astral matter, and these radiate from the Picture just as surely as scent inheres in and radiates from a flower.

Books are specially strong centres of thought-forms, and their unnoticed influence in a man's life is often a powerful one. It is, therefore, unwise to keep on one's bookshelves books of an unpleasant or undesirable character.

Talismans or amulets affect a man's life to some extent. They have already been described in The Etheric Double and The Astral Body. Briefly, they operate in two ways: [1] they radiate waves of their own which are intrinsically helpful; [2] the knowledge of the presence and purpose of the talisman awakens the faith and courage of the wearer and thus calls up the reserve strength of his own will.

If a talisman is "linked" with its maker, and the wearer calls upon the maker mentally, the ego will respond and reinforce the vibrations of the talisman by a strong wave of his own more powerful thought.

A talisman strongly charged with magnetism may thus be an invaluable help; the physical nature, as well as the emotions and the mind, have to be mastered, and the physical is, without doubt, the most difficult to deal with. Some people scorn such things as talismans; others have found the path to occultism so arduous that they are glad to avail themselves of any assistance that may be offered to them. The strongest talisman on this planet is probably the Rod of Power which is kept at Shamballa and used in Initiations and at other times.

A man is affected also by the colours of objects which surround him. For just as a feeling or thought produces in subtler matter a certain colour, so, conversely the presence of a given colour even in physical objects exerts a steady pressure, tending to arouse the feeling or thought appropriate to that colour. Hence the rationale, for example, of the use of certain selected colours by the Christian Church in altar frontals, vestments etc., in the endeavour to superinduce the condition of mind and feeling especially appropriate to the occasion.

A man is affected by the walls and furniture of his rooms because, by his thoughts and feelings he unconsciously magnetises physical objects near him, so that they possess the power of suggesting thoughts and feelings of the same type, either to himself or to any person who puts himself in the way of their influence. Striking instances of this phenomena occur, as is well known, in the case of prison cells and other similar places.

Hence, also, the value of "holy places", where the atmosphere is literally vibrating at a high rate. A room set apart for meditation and high thought soon gains an atmosphere purer and subtler than that of the surrounding world, and the wise student will take due advantage of this fact both for his own sake and for the helping of those around him.

As an example of this kind of thought-force, we may cite the case of certain ships or engines which have the reputation of being "unlucky". Instances have unquestionably occurred where accident after accident occurs in connection with them without apparent reason.

The effect could have been brought about in some such way as the following. Feelings of intense hatred may have been entertained against the builder of the ship or against her first captain. These feelings of themselves would probably not be sufficient actually to cause serious misfortune.

But in the life of every ship there are many occasions on which an accident is only just averted by vigilance and promptitude, in which a single moment's delay or slackness would be sufficient to precipitate a catastrophe. Such a mass of thought – forms as those described would be amply sufficient to cause that momentary lack of vigilance or momentary hesitation; and that would be the easiest line along which the malignity could work.

It is clear that the reverse is also true, and that a "lucky" atmosphere can be built up about material objects, etc., by the optimistic and cheerful thoughts of those who use the objects.

Similarly with regards to relics. Any article highly charged with personal magnetism may continue to radiate its influence for centuries with practically undiminished force. Even if the relic be not genuine, the force poured into it by centuries of devotional feeling will magnetise it strongly and make it a force for good.

There is thus occult wisdom in the following advice, quaint as it is in expression: "Knead love into the bread you bake; wrap strength and courage in the parcel you tie for the woman with the weary face; hand trust and candour with the coin you pay to the man with the suspicious eyes." The student of the Good Law has abundant opportunities of distributing blessings all about him unobtrusively, although the recipients may be quite unconscious of the source of that which comes to them.

As mentioned in Chapter XI, when dealing with Thought-Transference, physical association with a more highly evolved person may be of considerable help in the development and training of the mental body. Just as the heat radiations from a fire, warm articles placed near the fire, so may the thought-radiations of a thinker stronger than ourselves cause our mental bodies to vibrate sympathetically with him, and for the time being we feel our mental power increased.

An example of this effect often occurs at eg., a lecture; a person in the audience appears whilst he is listening to the speaker to understand fully what is being said, but later the conception seems to grow dim and maybe completely elude the mind when an attempt is made to reproduce it. The explanation is that, the masterful vibrations of the stronger thinker have at the time shaped the forms taken by the mental body of the listener, but afterwards that mental body is unable of its own power to resume those shapes.

A true teacher will thus aid his disciples far more by keeping him near than by any spoken words. Unseen entities associated with ocean, mountain, forest, waterfalls, etc., radiate vibrations which awaken unaccustomed portions of mental, astral and etheric bodies, and hence, from this point of view, travel may be beneficial to all three bodies.

In general, it may be said that everything which promotes health and well-being of the physical body reacts favourably also upon the higher vehicles.

The converse of course, is also true, the emotional and mental life having profound effects upon the physical body. For, while it is true that the mental and physical bodies are obviously, in the very nature of things, more amenable to the power of thought than is the physical body, yet the matter of even the physical body may be moulded by the power of emotion and thought. Thus for example, it is well known that any habitual line of thought, virtue or vice, makes its impress on the physical features, a phenomenon so common that its full significance has not perhaps been adequately realised by most people. Another example is that of the "stigmata", appearing on the bodies of saints, many instances of which are on record.

Innumerable other examples may be furnished from the literature of modern psychoanalysis and other sources.

In the highly evolved Fifth Race man of today, in fact, the physical body is largely ruled by mental conditions; hence anxiety, mental suffering and worry, producing nervous tension, readily disturb organic processes and bring about weakness and disease. Right thought and feeling react upon the physical body and increase its power to assimilate prana or vitality.

Mental strength and serenity thus directly promote physical health, for the evolved Fifth Race man lives his physical life literally in his nervous system.

[2] THE EMOTIONAL LIFE

The mental and astral bodies are so closely linked together as to produce profound effects upon one another.

The intimate association between kama [desire] and manas [mind], and their actions and reactions on each other, have already been dealt with in Chapter VI on Kama-Manas. In this chapter we will deal merely with a few further incidental effects of the astral on the mental body, and also with the effect of the mental body on the astral body.

A flood of emotion sweeping over the astral body does not itself greatly affect the mental body, although for the time it may render it almost impossible for any activity from that mental body to come through into the physical brain. That is not because the mental body itself is affected, but because the astral body, which acts as a bridge between the mental body and the brain, is vibrating so entirely at one rate as to be incapable of conveying any undulation which is not in harmony with that one rate.

A typical example of the effect of powerful emotion on mental activity is afforded by a man "in love"; while in this state the yellow of intellect entirely vanishes from his aura.

Coarse sensuality in the astral body, which is represented by a peculiarly unpleasant hue, is quite incapable of reproducing itself in the mental body. This is an example of the principle that the matter of the various planes, as it becomes finer, gradually loses the power of expressing the lower qualities.

Thus a man may form a mental image which evokes sensual feeling in him, but the thought and the image will express themselves in astral matter, and not in mental. It will leave a very definite impression of its peculiar hue upon the astral body, but in the mental body it will intensify the colours which represent its concomitant evils of selfishness, conceit and deception.

It sometimes happens that certain groups of feeling and thought, some desirable, some undesirable, are closely linked together. Thus for example, it is well known that deep devotion and a certain form of sensuality are frequently almost inextricably mingled.

A man who finds himself troubled by this unpleasant conjunction may reap the benefit of the devotion, without suffering from the ill-effects of the sensuality, by surrounding his mental body with a rigid shell so far as its lower sub-divisions are concerned. In this way he will effectually shut out the lower influences while still allowing the higher to play upon him unhindered. This is but one example of a phenomenon of which there are many varieties in the mental world.

The effect of the mental body on the astral body is, of course, considerable, and the student should pay close attention to this fact. He will recollect that each body is controlled ultimately by the body next above it. Thus the physical body cannot rule itself, but the passions and desires of the astral body can direct and control it.

The astral body, in its turn, must be trained and brought under control by the mental body, for it is by thought that we can change desire and begin to transmute it into will, which is the higher aspect of desire. Only by the Self as Thought can be mastered the Self as Desire.

The very sense of freedom in choosing between desires indicates that something higher than desire is operative, and that something higher is manas, in which resides freewill, so far as anything lower than itself is concerned.

The student will recollect also that the chakrams or force-centres of the astral body are built and controlled from the mental plane, just as the physical brain centres were built from the astral plane.

Every impulse sent by the mental body to the physical brain has to pass through the astral body, and as astral matter is far more responsive to thought vibrations than is physical matter, the effect on the astral body is proportionately greater. This process was dealt with in The Astral Body, p. 78, to which book the student is referred.

Hence as the vibrations of mental matter excite also those of astral matter, a man's thoughts tend to stir his emotions. Thus –as is well known –a man will sometimes, by thinking over what he considers his wrongs, easily make himself angry. The converse is equally true, though it is often forgotten. By thinking calmly and reasonably a man can prevent or dismiss anger or other undesirable emotions.

An example of the effect of a scientific and orderly habit of mind on the astral body is illustrated in Man Visible and Invisible on Plate XX, which portrays the astral body of a scientific type of man. The astral colours tend to fall into regular bands, and the lines of demarcation between them become clear and definite. In extreme cases the intellectual development leads to the entire elimination of devotional feeling, and considerably reduces sensuality.

The acquirement of concentration and, in general, the development of the mental body, also affects the dream life, and tends to make the dreams become vivid, well-sustained, rational, even instructive.

The astral body, in fact, ought to be, and in a developed man is, merely a reflection of the colours of the mental body, indicating that the man allows himself to feel only what his reason dictates.

Conversely, no emotion under any circumstances ought to affect the mental body in the least, for the mental body is the home, not of passions or emotions, but of thought.

[3] THE MENTAL LIFE

Although some little work in the building and evolution of a man's mind may be done from outside, yet most must result from the activity of his own consciousness, If, therefore a man would have a mental body strong, well-vitalised, active, able to grasp loftier thoughts presented to him, he must work steadily at right thinking.

Each man is the person who most constantly affects his own mental body. Others, such as speakers and writers, affect it occasionally, but he always. His own influence over the composition of his mental body is far stronger than that of anyone else, and he himself fixes the normal vibratory rate of his mind. Thoughts which do not harmonise with that rate will be flung aside when they touch his mind. if he thinks truth, a lie cannot make a lodgment in his mind; if he thinks love, hate cannot disturb him; if he thinks wisdom, ignorance cannot paralyse him.

The mind must not be allowed to lie as it were fallow, for then any thought-seed may take root in it and grow; it must not be allowed to vibrate as it pleases, for that means it will answer to any passing vibration. A man's mind is his own, and he should allow entrance only to such thoughts as he, the ego, chooses.

The majority of men do not know how to think at all, and even those who are a little more advanced rarely think definitely and strongly, except during the moments when they are actually engaged in some piece of work which demands their whole attention. Consequently large numbers of minds are always lying fallow, ready to receive what ever seed may be sown in them.

The vast majority of people, if they will watch their thoughts closely, will find that they are very largely made up of a casual stream of thoughts which are not their own thoughts at all, but simply the cast-off fragments of other people's. The ordinary man hardly ever knows exactly of what he is thinking at any particular moment, or why he is thinking of it. Instead of directing his mind to some definite point he allows it to run riot, or lets it lie fallow, so that any causal seed cast into it may germinate and come to fruition there.

A student who is earnestly trying to raise himself somewhat above the thought of the average man should bear in mind that a very large proportion of the insurgent thought which is so constantly pressing upon him is at a lower level than his own and, therefore, he needs to guard himself against its influence. There is a vast ocean of thought upon all sorts of utterly unimportant subjects that it is necessary to strive rigidly to exclude it. This is one reason why to "Tyle the Lodge" is the "constant care" of every Freemason.

If a man will take the trouble to form the habit of sustained and concentrated thought, he will find that his brain, trained to listen only to the promptings of the ego –the real Thinker –will remain quiescent when not in use, and will decline to receive and respond to casual currents from the surrounding ocean of thought, so that it will no longer be impervious to influences from the higher planes, where insight is keener and judgement truer than it ever can be down here.

It is only when the man can hold his mind steady, can reduce it to quietude, and keep it in that condition without thinking, that the higher consciousness can assert itself. Then is the man ready to enter on the practice of meditation and Yoga, as we shall see in due course.

That is the practical lesson in training the mental body. The man who practices it will discover that by thinking life can be made nobler and happier, and that it is true that by wisdom an end can be put to pain.

The wise man will watch his thought with the greatest care, realising that in it he possesses a powerful instrument, for the right use of which he is responsible. It is his duty to govern his thought lest it should run riot and do evil to himself and others. It is his duty to develop his thought-power because by means of it a vast amount of good can be done.

Reading does not build the mental body; thought alone builds it. Reading is valuable only as it furnishes materials for thought, and a man's mental growth will be in proportion to the amount of thought he expends in his reading. With regular and persistent –but not excessive –exercise, the power of thinking will grow just as muscle-power grows by exercise. Without such thinking the mental body remains loosely formed and unorganised; without gaining concentration –the power of fixing the thought on a definite point –thought-power cannot be exercise at all.

The law of life, that growth results from exercise, thus applies to the mental body just as it does to the physical body. When the mental body is exercised and made to vibrate under the action of thought, fresh matter is drawn in from the mental atmosphere and is built into the body, which thus increases in size as well as in complexity of structure. The amount of the thought determines the growth of the body, the quality of the thought determines the kind of matter employed in that growth.

We may profitably consider the method of reading a little more in detail. In a book that is carefully written, each sentence or paragraph contains a clear statement of a definite idea, the idea being represented by the author's thought-form. That thought-form is usually surrounded with various subsidiary forms which are the expressions of corollaries of necessary deductions from the main idea.

In the mind of the reader there should be built up an exact duplicate of the author's thoughtform, perhaps immediately, perhaps by degrees. Whether the forms indicating corollaries also appear depends on the nature of the reader's mind, i.e.,, whether he is quick to see in a moment all that follows from a certain statement.

A mentally undeveloped person cannot make a clear reflection at all, but builds up a sort of amorphous incorrect mass, instead of a geometrical form. Others may make a recognisable form, but with blunted edges and angles, or with one part out of proportion to the rest.

Others may make a kind of skeleton of it, showing that they have grasped the outline of the idea, but not in any living way and without any details. Yet others may touch one side of the idea and not the other, thus building half the form; or seize upon one point and neglect the rest.

A good student will reproduce the image of the central idea accurately and at once, and the surrounding ideas will come into being one by one as he revolves the central idea in his mind.

One of the principal reasons for imperfect images is lack of attention. A clairvoyant can often see a reader's mind occupied with half-a-dozen subjects simultaneously. In his brain are seething household cares, business worries, memory and anticipation of pleasures, weariness at having to study, and so forth, these occupying nine-tenths of his mental body, leaving the remaining one-tenth to make a despairing effort to grasp the thought-form he is supposed to be assimilating from the book.

The result of such fragmentary and desultory reading is to fill the mental body with a mass of little, unconnected thought-forms like pebbles, instead of building up in it an orderly edifice.

It is clear, therefore, that in order to be able to use the mind and the mental body effectively, training in paying attention and concentration are essential, and the man must learn to clear his mind of all extraneous and irrelevant thoughts whilst he is studying.

A trained student may, through the thought-form of the author, get into touch with the mind of he author, and obtain from him additional information or light on difficult points, though, unless the student is highly developed he will imagine that the new thoughts which come to him are his own instead of those of the author.

Remembering that all mental work done on the physical plane must be done through the physical brain in order to succeed, the physical brain must be trained and ordered so that the mental body can work readily through it.

It is well known that certain parts of the brain are connected with certain qualities in the man, and with his power to think along certain lines: all these must be brought into order and duly correlated with the zones in the mental body.

A student of occultism of course trains himself deliberately in the art of thinking; consequently his thought is much more powerful than that of the untrained man, and is likely to influence a wider circle and to produce a much greater effect. This happens quite outside his own consciousness without his making any specific effort in the matter.

But because the occultist has learned the tremendous power of thought, his responsibility in the right use of it is proportionately the greater, and he will take pains to utilise it for the helping of others.

A warning may not be out of place to those who have a tendency to be argumentative. Those who are easily provoked to argument should recollect that when they rush out eagerly to verbal battle they throw open the doors of their mental fortress, leaving it undefended. At such times any thought- forces which may happen to be in their neighbourhood can enter and possess their mental bodies. While strength is being wasted over points which are often of no importance, the whole tone of their mental bodies is being steadily deteriorated by the influences which are flowing into it.The occult student should exercise great care in permitting himself to enter into arguments. It is a common experience that argument seldom tends to alter the opinion of either side; in most cases it confirms the opinions already held.

Every hour of life gives opportunity for consciousness to build up the mental vehicle. Waking or sleeping we are ever building our mental bodies. Every quiver of consciousness, though it be due only to a passing thought, draws into the mental body some particles of mental matter and shakes out other particles from it. If the mental body is made to vibrate by pure and lofty thoughts, the rapidity of the vibrations causes particles of the coarser matter to be shaken out and their place is taken by finer particles. In this way the mental body can be made steadily finer and purer. A mental body thus composed of finer materials, will give no response to coarse and evil thoughts; a mental body built of gross materials will be affected by evil passersby and will remain unresponsive to and unbenefited by the good.

The above applies more specifically to the "form-side" of the mental body. Turning to the "lifeside", the student should also bear in mind that the very essence of consciousness is constantly to identify itself with the Not-Self, and as constantly to re-assert itself by rejecting the Not-Self. Consciousness, in fact, consists of this alternating assertion and negation – "I am this" –"I am not this". Hence consciousness is, and causes in matter, the attracting and repelling that we call vibration. Thus the quality of the vibrations set up by the consciousness determines the fineness or coarseness of the matter which is drawn into the mental body.

As we saw in Chapter XI, the thought-vibrations of another, whose thoughts are lofty, playing on us tend to arouse vibrations in our mental bodies of such matter as is capable of responding, and these vibrations disturb and even shake out some of that which is too coarse to vibrate at his high rate of activity. Hence the benefit we receive from another is largely dependent upon our own past thinking because, to be beneficially affected, we must first have in our mental bodies some of the higher types of matter which his thought can affect.

The mental body is subject to the laws of habit just as are the other vehicles. Hence, if we accustom our mental bodies to a certain type of vibration, they learn to reproduce it easily and readily. Thus for example, if a man allows himself to think evil of others it soon becomes easier habitually to think evil of them than good. In such ways often arise prejudices which blind a man to the good points of others, and enormously magnify the evil in them.

Many persons, through ignorance, fall into habits of evil thought; it is, of course, equally possible to form habits of good thoughts. It is not a difficult matter to train oneself to look for the desirable rather than the undesirable qualities in the people whom we meet.

Hence will arise the habit of liking, rather than disliking people. By such practices, our minds begin to work more easily along the grooves of admiration and appreciation instead of along those of suspicion and disparagement. A systematic use of thought-power will thus be make life easier and pleasanter, and also build the right kind of matter into our mental bodies.

Many people do not exercise their mental abilities as much as they should do; their minds are receptacles rather than creators, constantly accepting other people's thoughts instead of forming their own from within.

A realisation of this fact should induce man to change the attitude of his consciousness in Daily life and to watch the working of his mind. At first considerable distress may be felt when a man perceives that much of his own thinking is not his own at all; that thoughts come to him he knows not whence, and take themselves off again he knows not whither; that his mind is little more than a place through which thoughts are passing.

Having reached this preliminary stage of mental self-consciousness, a man should next observe what difference there is between the condition of thoughts when they come into his mind and when they go out of it –i.e.,, what it is that he himself has added to them during their stay with him. In this way his mind will rapidly become really active and develop its creative powers.

Next the man should choose with the utmost deliberation what he will allow to remain in his mind. When he finds there a thought that is good he will dwell upon it and strengthen it, and send it out again as a beneficent agent. When he finds in his mind a thought that is evil he will promptly eject it.

The careless play of thought on undesirable ideas and qualities is an active danger, creating a tendency towards such undesirable things, and leading to actions embodying them. A man who dallies in thought with the idea of an evil action may find himself performing it before he realises what he is doing. When the gate of opportunity swings open the mental action rushes out and precipitates action.For all action springs from thought; even when action is performed –as we say –without thought, it is nevertheless the instinctive expression of the thoughts, desires and feelings which the man has allowed to grow within himself in earlier days.

After pursuing steadily for some time this practice of choosing what thoughts he will harbour, the man will find that fewer and fewer evil thoughts flow into his mind; that such thoughts, in fact, will be thrown back by the automatic action of the mind itself. His mind also will begin to act as a magnet for all the similar thoughts that are around him. Thus the man will gather into his mental body a mass of good material and his mental body will grow richer in its content every year.

Thus we see that the great danger to be avoided is that of allowing the creation of thoughtimages to be incited from without, of allowing stimuli from the outer world to call up images in the mental body, to throw the creative mental matter into thought-forms, charged with energy, which will necessarily seek to discharge and thus realise themselves. In this ungoverned activity of the mental body lies the source of practically all our inner struggle and spiritual difficulties. It is ignorance which permits this undisciplined functioning of the mental body; that ignorance should be replaced by knowledge, and we should learn to control our mental bodies, so that they are not roused from without to making images, but are ours to use as we will.

An immense amount of suffering is caused by undisciplined imagination. The failure to control the lower passions [especially sex-desire] is the result of an undisciplined imagination, not of a weak will. Even though strong desire is felt, it is creative thought which brings about action.

There is no danger in merely seeing or thinking about the object of desire, but when a man imagines himself as giving way to his desires, and allows the desires to strengthen the image he has made, then his danger begins. It is important to realise that there is no power in objects of desire as such, unless and until we indulge in imaginations which are creative.Once having done this, struggle is certain to ensue.

In this struggle we may call upon what we think is our will, and try to escape from the results of our own imaginings by frantic resistance. Few have learnt that anxious resistance inspired by fear are very different from will. The will should rather be employed to control the imagination in the first instance, thus eradicating the cause of our troubles at its source and origin.

As we shall see in a later chapter, the materials which we gather during the present life are, in the after-death life, worked up into mental powers and faculties which will find further expression in our future lives. The mental body of the next incarnation depends on the work we are doing in our present mental body. Karma brings the harvest according to our sowing; we cannot isolate one life from another, nor miraculously create something out of nothing.

As it is written in the Chandogyopanishat, "Man is a creature of reflection; that which he reflects on in this life he becomes the same hereafter."

To combat and change habits of thought, a process which involves ejecting from the mental body one set of mental particles and replacing them by others of a higher type, is naturally difficult at first, just as it is usually difficult at first to break physical habits. But it can be done and, as the old form changes, right thinking becomes increasingly easy, and finally spontaneous.

There is hardly any limit to the degree to which a man may re-create himself by concentrated mental activity. As we have seen, schools of healing –such as Christian Science, Mental Science, and others –utilise this powerful agency in obtaining their results, and their utility largely depends upon the knowledge of the practitioner as to the forces which he is employing. Innumerable successes prove the existence of the force; failures show that the manipulation of it was not skilful or could not evoke sufficient for the task in hand.

Expressed in general terms, thought is the manifestation of Creativeness, the Third Aspect of the human triplicity. In Christian terminology will is the manifestation of God the Father; love of God the Son; and thought, or creative activity, of God the Holy Ghost. For it is thought in us which acts, which creates, and carries out the decrees of the will. If the will is the King, thought is the Prime Minister.

The occultist applies this creative power to quicken human evolution. Eastern Yoga is the application of the general laws of the evolution of mind to this quickening of the evolution of a particular consciousness. It has been proved, and can ever be re-proved, that thought, concentrating itself attentively on any idea, builds that idea into the character of the thinker, and a man may thus create in himself ant desired quality by sustained and attentive thinking –by meditation.

Knowing this law, a man can build his own mental body as he wishes it to be as certainly as a bricklayer can build a wall. The process of building character is as scientific as that of developing muscular power. Even death does not stop the work, as we shall see in later chapters. In this work prayer may be used with great effect, perhaps the most striking instance being found in the life of the Brahman. The whole of that life is practically one continuous prayer.

Though much more elaborate and detailed, it is somewhat similar to the form used is some Catholic convents where the novice is instructed to pray every time that he eats, that his soul may be nourished by the bread of life; every time he washes that his soul may be kept püre and clean; every time he enters a church, that his life may be one long service; and so on. The life of the Brahman is similar, except that his devotion is on a larger scale and is carried into much greater detail. No one can doubt that he who really and honestly obeys all these directions must be deeply and constantly affected by such action.

As we saw in Chapter IV, the mental body has this peculiarity, that it increases in size as well, of course, as in activity, as the man himself grows and develops. The physical body, as we know, has remained substantially the same size for long ages; the astral body grows to some extent; but the mental body [as well as the causal body] expands enormously in the later stages of evolution, manifesting the most gorgeous radiance of many-coloured lights glowing with intense splendour when at rest, and sending forth dazzling coruscations when in high activity.

In a very undeveloped person the mental body is even difficult to distinguish; it is so little evolved that some care is needed to see it at all. Large numbers of people are as yet incapable of clear thought, especially in the West with regard to religious matters. Everything is vague and nebulous. For occult development, vagueness and nebulosity will not do. Our conceptions must be clear-cut and our thought-images definite. These apart from other characteristics, are essentials in the life of the occultist.

The student should realise also that each man necessarily views the external world through the medium of his own mind. The result may be aptly compared to looking at a landscape through coloured glass. A man who has never seen except through red or blue glasses would be unconscious of the changes which these made on the true colours of the landscape.

Similarly, a man is usually entirely unconscious of the distorting effect due to his seeing everything through the medium of his own mind. It is in this somewhat obvious sense that the mind has been called the "creator of illusion." The student of occultism clearly has the duty of so purifying and developing his mental body, eliminating "warts" [see p.31] and prejudices, so that his mental body reflects the truth with a minimum of distortion due to the defects of the mental body.

The effect of a man on animals is a matter which we should deal briefly in order to make complete our study of the mental body, its actions and reactions.

If a man turns affectionate thought upon an animal, or makes a distinct effort to teach him something, there is a direct and intentional action passing from the astral or mental body of the man to the corresponding vehicle of the animal. This is comparatively rare, the greater portion of the work done being without any direct volition on either side, simply by the incessant and inevitable action due to the proximity of the two entities concerned.

The character and type of the man will have a great influence on the destiny of the animal. If the interaction between them is mainly emotional, the probability is that the animal will develop mainly through his astral body, and that the final breaking of the link with the group-soul will be due to a sudden rush of affection which will reach the buddhic aspect of the monad floating above it, and thus cause the formation of the ego.

If the interaction is mainly mental, the nascent mental body of the animal will be stimulated, and the animal will probably individualise through the mind.

If a man is intensely spiritual or of strong will, the animal will probably individualise through the stimulation of his will. Individualisation through affection, intellect, and will are the three normal methods. It is also possible to individualise by less desirable means, eg., through pride, fear, hate, or lust for power.

Thus for example, a group of about two million egos individualised in the Seventh Round of the Moon Chain entirely through pride, possessing but little of any quality other than a certain cleverness, their causal bodies consequently showing almost no colour but orange.

The arrogance and unruliness of this group caused all through history constant trouble to themselves and to others. Some of them became the "Lords of the Dark Face" in Atlantis, others became world-devastating conquerors or unscrupulous millionaires, well called "Napoleons of finance".

Some of those who individualised through fear, engendered by cruelty, became the inquisitors of the –[page 110]—Middle Ages, and those who torture children at the present day.

Further details on the mechanisms of individualisation will be found in A Study of Consciousness, by Dr. Besant, pp. 172-3. It will also be dealt with in The Causal Body.

CHAPTER XIV

FACULTIES

The mental body, like the astral body, can in process of time be aroused into activity, and will learn to respond to the vibrations of the matter of its own plane, thus opening up before the ego an entirely new and far wider world of knowledge and power.

The full development of consciousness in the mental body must not however, be confounded with merely learning to use the mental body to some extent. A man uses his mental body whenever he thinks, but that is very far from being able to utilise it as an independent vehicle through which consciousness can be fully expressed.

As we saw before [p. 20], the mental body of the average man is much less evolved than is his astral body. In the majority of men the higher portions of the mental body are as yet quite dormant, even when the lower portions are in vigorous activity. The mental body of an average man, in fact, is not yet in any true sense a vehicle at all, for the man cannot travel about in it nor can he employ its senses for the reception of impressions in the ordinary way.

Among the scientific men of our time, although the mental body will be very highly developed, yet this will be chiefly for use in the waking consciousness and very imperfectly as yet for direct reception on the higher planes.

Very few, apart from those who have been definitely trained by teachers belonging to the Great

Brotherhood of Initiates, consciously work in the mental body; to be able to do so means years of practice in meditation and special effort.

Up to the time of the First Initiation, a man works at night in his astral body, but as soon as it is perfectly under control and he is able to use it fully, work in the mental world is begun. When the mental body is completely organised, it is a far more flexible vehicle than the astral body, and much that is impossible on the astral plane can be accomplished therein.

The power to function freely in the mental world must be acquired by the candidate for the Second Initiation because that Initiation takes place on the lower mental plane.

Just as the vision of the astral plane is different from that of physical plane, so is the vision of the mental plane totally different from either. In the case of mental vision, we can no longer speak of separate senses such as sight and hearing, but rather have to postulate one general sense which responds so fully to the vibrations reaching it that when any object comes within its cognition it at once comprehends it fully, and, as it were, sees it, hears it, feels it, and knows all there is to know about it, its cause, its effects, its possibilities, so far at least as the mental and lower planes are concerned, by the one instantaneous operation. There is never any doubt, hesitation, or delay about this direct action of the higher sense.

If he thinks of a place he is there; if of a friend, that friend is before him. No longer can misunderstandings arise, no longer can he be deceived or misled by any outward appearances, for every thought and feeling of his friend lies open as a book before him on that plane.

If the man is with a friend whose higher sense is also opened their intercourse is perfect beyond all earthly conception. For them distance and separation do not exist; their feelings are no longer hidden, or at best but half expressed by clumsy words; question and answer are unnecessary, for the thought-pictures are read as they are formed, and the interchange of ideas is as rapid as is their flashing into existence in the mind. Yet even this wonderful faculty differs in degree only and not in kind from those which are at our command at the present time. For on the mental plane, just as –[page 113]—on the physical , impressions are still conveyed by means of vibrations travelling from the object seen to the seer. This condition does not apply on the buddhic plane; but with that we are not concerned in this book.

There is not very much that can or should be said regarding mental clairvoyance, because it is highly improbable that any example of it will be met with except among pupils properly trained in some of the highest schools of occultism. For them it opens up a new world in which all that we can imagine of utmost glory and splendour is the commonplace of existence.

All that it has to give –all of it at least that he can assimilate –is within the reach of the trained pupil, but for the untrained clairvoyant to touch it is hardly more than a bare possibility.

Probably not one in a thousand among ordinary clairvoyants ever reach it at all. It has been reached in mesmeric trance when the subject has slipped from the control of the operator, but the occurrence is exceedingly rare, as it needs almost superhuman qualifications in the way of lofty spiritual aspiration and absolute purity of thought and intention upon the part both of the subject and the operator. Even in such cases the subject has rarely brought back more than a faint recollection of an intense but indescribable bliss, generally deeply coloured by his personal religious convictions.

Not only is all knowledge –all, that is, which does not transcend the mental plane –available to those functioning on the mental plane, but the past of the world is as open to them as the present, for they have access to the indelible memory of nature [see Chapter XXVIII].

Thus for example, for one who can function freely in the mental body there are methods of getting at the meaning of a book quite apart from the process of reading it. The simplest is to read from the mind of one who has studied it; but this, of course, is open to the objection that one reaches only the student's conception of the book.

A second plan is to examine the aura of the book. Each book is surrounded by a thought – aura built up by the thoughts of all who have read and studied it. Thus the psychometrisation of a book generally yields a fairly full comprehension of its contents; though of course, there may be a considerable fringe of opinions held by the various readers but not expressed in the book itself.

As mentioned in Chapter VIII, in view of the fact that few readers at the present day seem to study so thoughtfully and thoroughly as did the men of old, the thought-forms connected with a modern book are rarely so precise and clear-cut as those which surround the manuscripts of the past.

A third plan is to go behind the book or manuscript altogether and touch the mind of the author, as described in Chapter X. Yet a fourth method, requiring higher powers, is to psychometrise the subject of the book and visit mentally the thought-centre of that subject where all the streams of thought about the subject converge. This matter has been dealt with in Chapter XII on Thought-Centres.

In order to be able to make observations on the mental plane, it is necessary for a man very carefully to suspend his thought for a time, so that its creations may not influence the readily impressible matter around him, and thus alter entirely the conditions so far as he is concerned.

This holding the mind in suspense must not be confounded with the blankness of mind, towards the attainment of which so many Hatha Yoga practices are directed. In the latter case the mind is dulled down into absolute passivity, the condition closely approaching mediumship.

In the former the mind is keenly alert and positive as it can be, holding its thought is suspense for the moment merely to prevent the intrusion of a personal equation into the observation which it wishes to make. Chakrams, or Force-Centres, exist in the mental body just as they do in all the other vehicles.

They are points of connection at which force flows from one vehicle to another. The chakrams in the etheric body have been described in the Etheric Body, p. 22, etc., and those in the astral body in The Astral Body, p. 31, etc. At present there is very little information available regarding the chakrams in the mental body.

One item of information is the following: In one type of person the chakram at the top of the head is bent or slanted until its vortex coincides with the atrophied organ known as the pineal gland, which is by people of this type vivified and made into a line of communication directly with the lower mental, without apparently passing through the intermediate astral plane in the ordinary way. It was for this type that Madame Blavatsky was writing when she laid such emphasis upon the awakening of that organ.

Another fact is that the faculty of magnification, called by the Hindus anima, belongs to the chakram between the eyebrows. From the centre portion of that chakram is projected what we may call a tiny microscope, having for its lens only one atom, thus providing an organ commensurate in size with the minute objects to be observed.

The atom employed may be either physical, astral or mental, but whichever it is it needs a special preparation. All its spirillae must be opened up and brought into full working order so that it is just as it will be in the seventh round of our chain.

The power belongs to the causal body, so if an atom of lower level be used as an eye-piece, a system of reflecting counterparts must be introduced. The atom can be adjusted to any subplane, so that any required degree of magnification can be applied in order to suit the object which is being examined.

A further extension of the power enables the operator to focus his consciousness in the lens, and then to project it to distant points.

The same power also, by a different arrangement, can be used for diminishing purposes when one wishes to view as a whole something far too large to be taken in at once by ordinary vision. This is known to the Hindus as Mahima.

There is no spatial limit to mental clairvoyance beyond that of the mental plane itself, which, as we shall see in Chapter XXVII, does not extend to the mental planes of other planets.

Nevertheless, it is possible by mental clairvoyance to obtain a good deal of information about other planets.

By passing outside of the constant disturbances of the earth's atmosphere, it is possible to make sight enormously clearer. It is also not difficult to learn how to put on an exceedingly high magnifying power, by means of which very interesting astronomical information may be gained.

Prana or Vitality exists on the mental plane, as it does on all planes of which we know anything. The same is true with regard to Kundalini or the Serpent-Fire, and also with regard to

Fohat or electricity, and to the life-force referred to as The Etheric Double as the Primary Force.

Of Prana and Kundalini on the mental plane scarcely anything appears at present to be known.

We know, however, that Kundalini vivifies all the various vehicles.

The Primary Force, mentioned above, is one of the expressions of the Second Outpouring from the Second Aspect of the Logos. On the Buddhic level it manifests itself as the Christprinciple in man; in the mental and astral bodies it vivifies various layers of matter, appearing in the higher part of the astral as a noble emotion, and in the lower part as a mere rush of lifeforce energising the matter of that body. In its lowest embodiment it is clothed in etheric matter, and rushes from the astral body into the chakrams in the surface of the etheric body, where it meets the kundalini which wells up from the interior of the human body.

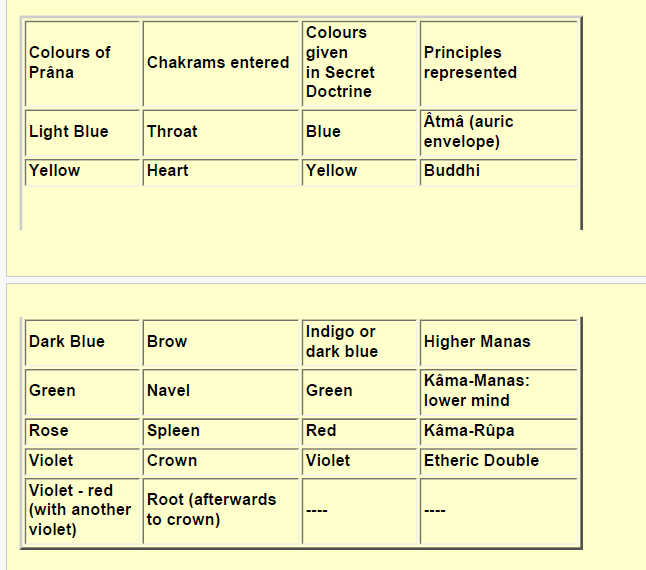

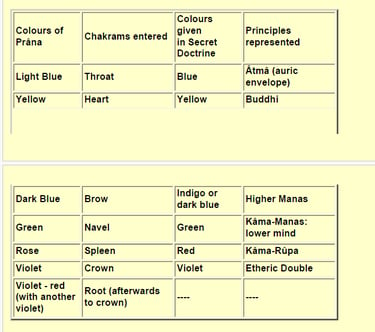

The student will recollect [vide The Etheric Double p.44] that the stream of violet prana stimulates thought and emotion of a high spiritual type, ordinary thought being stimulated by the action of the blue stream mingled with part of the yellow; also that in some kinds of idiocy the flow of vitality to the brain, both yellow and blue-violet, is almost entirely inhibited.

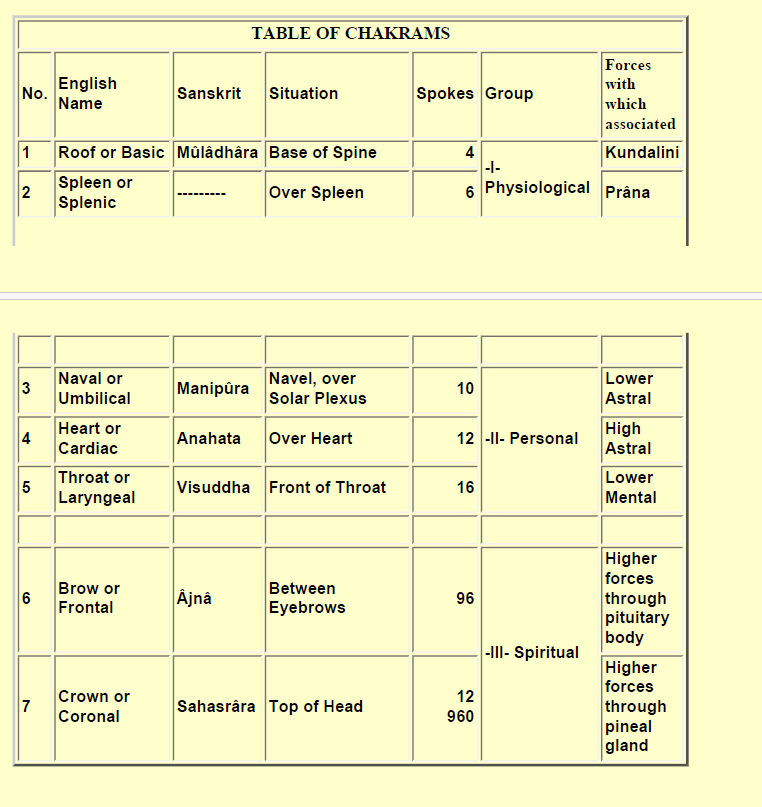

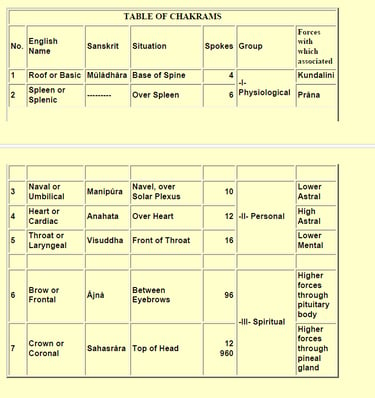

Since The Etheric Double was published, C.W.Leadbeater's book The Chakras has appeared, containing some new and valuable information regarding the chakras, and particularly regarding the connection between the various centres or chakrams and the planes. The student therefore, may find the following tables useful:

From the above it appears that the Primary Force, Prana and Kundalini, are not directly connected with man's mental and emotional life, but only with his bodily well being. There are, however, also other forces entering the chakrams which may be described as psychic and spiritual. The basal and splenic chakrams exhibit none of these, but the navel and higher chakrams are ports of entry for forces which affect human consciousness.

There seems to be a certain correspondence between the colours of the streams of prana which flow to the several chakrams and the colours assigned by H.P. Blavatsky to the principles of man in the diagram in The Secret Doctrine, Vol. III, p. 452, as shown in the following table.

Kundalini belongs to the First Outpouring, coming from the Third Aspect. In the centre of the earth it operates in a vast globe, only the outer layers of which can be approached; these are in sympathetic relationship with the layers of Kundalini in the human body. Thus the Kundalini in the human body comes from what has been called the "laboratory of the Holy Ghost" deep down in the earth. It belongs to the fire of prana and vitality. Prana belongs to air and light and open spaces; the fire from below is much more material, like the fire in a red-hot iron. There is a rather terrible side to this tremendous force; it gives the impression of descending deeper and deeper into matter, of moving slowly but irresistibly onwards, with relentless certainty.

It should be noted that Kundalini is the power of the First Outpouring on its path of return and it works in intimate contact with the Primary Force already mentioned, and the two together bringing an evolving creature to the point where it can receive the Outpouring of the First Logos and become a human ego.

The premature unfoldment of Kundalini has many unpleasant possibilities. It intensifies everything in the man's nature, and it reaches the lower and evil qualities more readily than the good. In the mental body, for example, ambition is very readily aroused, and soon swells to an incredibly inordinate degree. It would be likely to bring with it a great intensification of the power of intellect, but at the same time it would produce abnormal and satanic pride, such as is quite inconceivable to the ordinary man. No uninstructed man should ever try to arouse it, and if such an one finds that it has been aroused by accident, he should at once consult someone who fully understands these matters.It has been said in the Hathayogapradipika [III. 107] : "It gives liberation to Yogis, and bondage to fools".