THE MENTAL BODY , PART-4

THE MENTAL BODY , PART-4. Meditation has many objects, of which the principal ones are as follows: [1] It ensures that at least once a day a man shall think of high and holy things, his thoughts being taken away from the petty round of daily life, from its frivolities and its troubles.

GİZLİ ÖĞRETİLER

THE MENTAL BODY,PART-4

CHAPTER XVI

MEDITATION

Concentration is, of course, not an end in itself, but a means to an end. Concentration fashions the mind into an instrument which can be used at the will of the owner. When a concentrated mind is steadily directed to any object, with a view to piercing the veil and reaching the life, and drawing that life into union with the life to which the mind belongs –then meditation is performed. Concentration is thus the shaping of the organ; meditation is its exercise.

As we have seen, concentration means the firm fixing of the mind on one single point without wandering, and without yielding to any distractions caused by external objects, by the activity of the senses or by that of the mind itself. It must be braced up to an unswerving steadiness and fixity, until gradually it will learn so to withdraw its attention from the outer world and from the body that the senses will remain quiet and still, while the mind is intensely alive and all its energies drawn inwards, to be launched at a single point of thought, the highest to which it can attain. When it is able to hold itself thus with comparative ease it is ready for a further step, and by a strong but calm effort of the will it can throw itself beyond the highest thought it can reach, while working in the physical brain, and in that effort will rise to, and unite itself with, the higher consciousness, and find itself free of the body.

Thus anyone who is able to pay attention, to think steadily on one subject for a little time without letting the mind wander, is ready to begin meditation.

We may define meditation as the sustained attention of the concentrated mind in face of an object of devotion of a problem that needs illumination to be intelligible, of anything, in fact, whereof the life is to be realised and absorbed, rather than the form. It is the art of considering a subject or turning it over in the mind in its various bearings and relationships.

Another definition of meditation is that it consists of the endeavour to bring into the waking consciousness, that is, into the mind in its normal state of activity, some realisation of the super-consciousness, to create by the power of aspiration a channel through which the influence of the divine or spiritual principle –the real man –may irradiate the lower personality.

It is the reaching out of the mind and feelings towards and ideal, and the opening of the doors of the imprisoned lower consciousness to the influence of the ideal. "Meditation", said H.P. Blavatsky, "is the inexpressible longing of the inner man for the Infinite". St. Alphonus de ‘ Liguori spoke of meditation as :"the blessed furnace in which souls are inflamed with Divine Love."

The ideal chosen may be abstract, such as a virtue; it may be the Divinity in man; it may be personified as a Master of Divine teacher. But in all cases it is essentially an uplifting of the soul towards its divine source, the desire of the individual self to become one with the Universal Self.

What food is to the physical life, so is meditation to the spiritual life. The man of meditation is ever the most effective man of the world. Lord Rosebery, speaking of Cromwell, described him as a "practical mystic", and declared that a practical mystic is the greatest force in the world.

The concentrated intellect, the power of withdrawing outside the turmoil, means immensely increased energy in work, more steadiness, self-control, serenity. The man of meditation is the man who wastes not time, scatters no energy, misses no opportunity. Such a man governs events, because within him is the power whereof events are only the outer expression; he shares the divine life, and therefore shares the divine power.

As was said before, when the mind is kept shaped to one image, and the Knower steadily contemplates it, he obtains a far fuller knowledge of the object than he could obtain by means of any verbal description of it.As concentration is performed, the picture is shaped in the mental body, and concentration on rough out-line, derived from, say, a verbal description, fills in more and more detail, as the consciousness comes more closely in touch with the things described.

All religions recommend meditation, and its desirability has been recognised by every school of philosophy. Just as a man who wishes to be strong uses prescribed exercises to develop his muscles, so the student of occultism uses definite and prescribed exercises to develop his astral and mental bodies.

There are, of course, many kinds of meditation, just as there are many types of men: it is clearly not possible that one method of meditation which is most suited to him.

Meditation has many objects, of which the principal ones are as follows:

[1] It ensures that at least once a day a man shall think of high and holy things, his thoughts being taken away from the petty round of daily life, from its frivolities and its troubles.

[2] it accustoms the man to think of such matter, so that after a time they form a background to his daily life, to which his mind returns with pleasure when it is released from the immediate demands of his business.

[3] It serves as a kind of astral and mental gymnastics, to preserve these higher bodies in health and to keep the stream of divine life flowing through them. For these purposes it should be remembered that the regularity of the exercises is of the first importance.

[4] it may be used to develop character, to build into it various qualities and virtues.

[5] It raises the consciousness to higher levels, so as to include the higher and subtler things; through it a man may rise to the presence of the Divine.

[6] it opens the nature and calls down blessings from higher planes.

[7] It is the way, even though it be only the first halting step upon the way, which leads to higher development and wider knowledge, to the attainment of clairvoyance, and eventually to the higher life beyond this physical world altogether.

Meditation is the readiest and safest method of developing the higher consciousness. It is unquestionably possible for any man in process of time, by meditation, say, upon the Logos or the Master, to raise himself first to the astral and then tot he mental levels; but of course, none can say how long it will take, as that depends entirely upon the past of the student and the efforts he makes.

A man occupied in the earnest study of higher things is for the time lifted entirely out of himself, and generates a powerful though-form in the mental world, which is immediately employed as a channel by the force hovering in the world nest above.

When a body of men join together in thought of this nature, the channel which they make is out of all proportion larger in its capacity than the sum of their separate channels. Such a body of men is, therefore, an inestimable blessing to the community amidst which it works.

In their intellectual studies they may be the cause of an outpouring into the lower mental world of force which is normally peculiar to the higher mental.

If their thought deals with ethics and soul-development in its higher aspects, they may make a channel of more elevated thought through which the force of the buddhic world may descend into the mental.

They are thus able to cause influence to be radiated out upon many a person who would not be in the least open to the action of that force if it had remained on its original level.

This, in fact, is the real and greatest function of, for example, a Lodge of the Theosophical Society –to furnish a channel for the distribution of the Divine Life. For every Lodge of the Theosophical Society is a centre of interest to the Masters of the Wisdom and Their pupils; consequently the thoughts of the members of the Lodge, when engaged in study, discussion, etc., may attract the attention of the Masters, a force being then poured out far more exalted than anything deriving from the members themselves.

Members of the Theosophical Society may be reminded that it has been stated by Dr. Besant that a Master has said that when a person joins the Society he is connected with Them by a tiny thread of life. This thread is the line of magnetic rapport with the Master, and the student may by arduous effort, by devotion and unselfish service, strengthen and enlarge the thread until it becomes a line of living light.

It is possible to call down a blessing from a still higher source. The Life and Light of the Deity flood the whole of His system, the force at each level or plane being normally strictly limited to it. If, however, a special channel be prepared for it, it can descend to, and illuminate a lower level.

Such a channel is always provided whenever any thought or feeling has an entirely unselfish aspect. Selfish feeling moves in a closed curve, and so brings it own response on its own level.

An utterly unselfish emotion is an outrush of energy which does not return, but in its upward movement provides a channel for a downpouring of divine Power from the level next above. This is the reality lying at the back of an idea of the answer to prayer. To a clairvoyant this channel is visible as a great vortex, a kind of gigantic cylinder or funnel.

This is the nearest explanation that can be given in the physical world, but it is inadequate, because as the force flows down through the channel it somehow makes itself one with the vortex, and issues from it coloured by it and bearing with it, distinctive characteristics which show through what channel is has come.

By meditation a man's astral and mental bodies gradually come out of chaos into order, slowly expand and gradually learn to respond to higher and higher vibrations. Each effort helps to thin the veil that divides him from the higher world and direct knowledge. His thought-forms grow day by day more definite, so that the life poured into them from above becomes fuller and fuller.

Meditation thus helps to build into the bodies the higher types of matter. It often leads to lofty emotions being experienced, these coming from the buddhic level and being reflected in the astral body. In addition, there is needed also development of the mental and causal bodies, in order to give steadiness and balance; otherwise fine emotions which sway the man in the right direction may very readily become a little twisted and sway him along other and less desirable lines. With feeling alone perfect balance or steadiness can never be obtained. The directing power of mind and will is needed as well as the motive force of emotion.

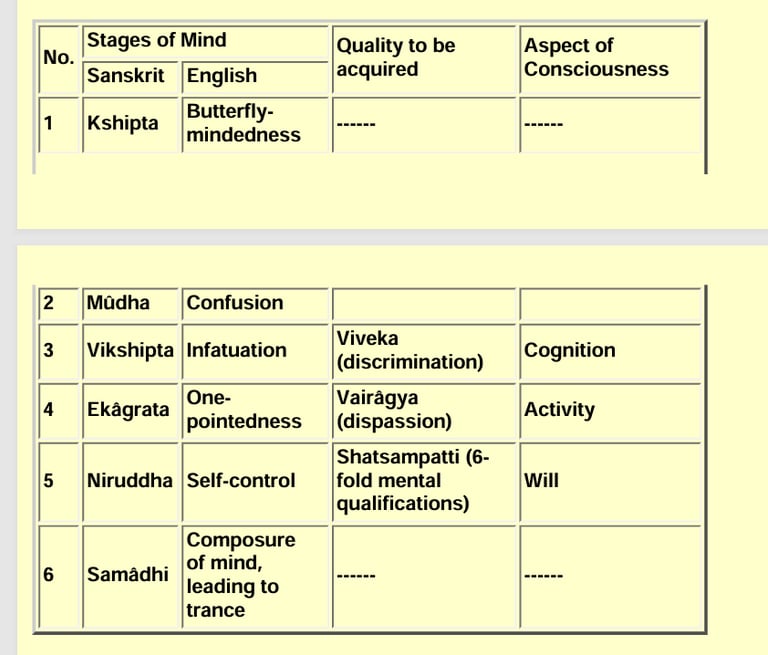

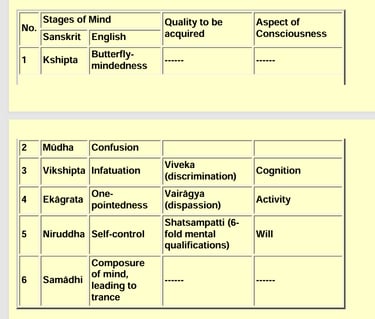

In practising meditation the student may find useful a knowledge of the five stages of mind as expounded by Patanjali. He should recollect, however, that these stages are not confined to the mental plane, but exist, in appropriate form, on every plane. They are:-

[1] Kshipta: the butterfly mind, which darts constantly from one object to another. It corresponds to activity on the physical plane.

[2] Mudha: the confused stage in which the man is swayed and bewildered by emotions; it corresponds to activity in the astral world.

[3] Vikshipta: the state of pre-occupation of infatuation by an idea; the man is possessed, we might say obsessed, by an idea. This corresponds to activity in the lower mental world. The man should learn Viveka [see p. 294], which has to do with the Cognitional aspect of consciousness.

[4] Ekagrata: one-pointedness; the state of possessing an idea, instead of being possessed by it. This corresponds to activity on the higher mental plane.

The man should here learn Vairagya [see p. 295], which has to do with the Activity aspect of consciousness.

[5] Niruddha: self-control; rising above all ideas, the man chooses as he wills according to his illumined Will. This corresponds to activity on the buddhic plane. The man should here learn Shatsampatti [see p. 294], which has to do with the Will aspect of consciousness.

When complete control has been acquired, so that the man can inhibit all motions of the mind, then he is ready for Samadhi, corresponding to Contemplation, with which we shall deal more fully in our next chapter. Meanwhile, for the sake of completeness, it is desirable to give here a preliminary idea of Samadhi.

Etymologically Samadhi means "fully placing together", and may therefore be rendered into English as "com-posing the mind", i.e.,, collecting it all together, checking all distractions.

"Yoga", says Vyasa, "is the composed mind". This is the original meaning of Samadhi, though it is more often used to denote the trance state, which is the natural result of perfect composure.

Samadhi is of two kinds:

[1] Samprajnata Samadhi, i.e.,, Samadhi with consciousness, with consciousness turned outwards towards objects;

[2] Asamprajnata Samadhi, i.e.,, Samadhi without consciousness, with consciousness turned inwards, withdrawn into itself so that it passes into the next higher vehicle.

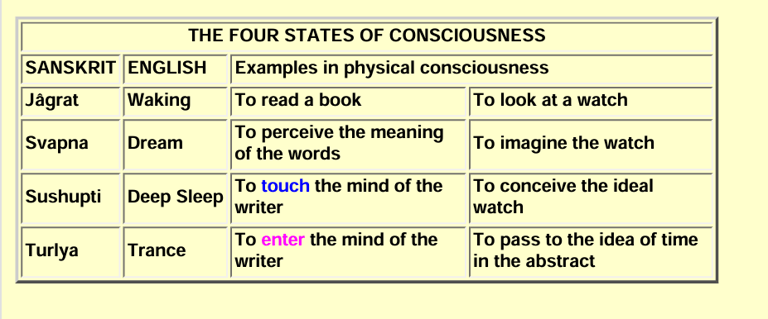

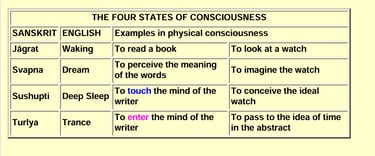

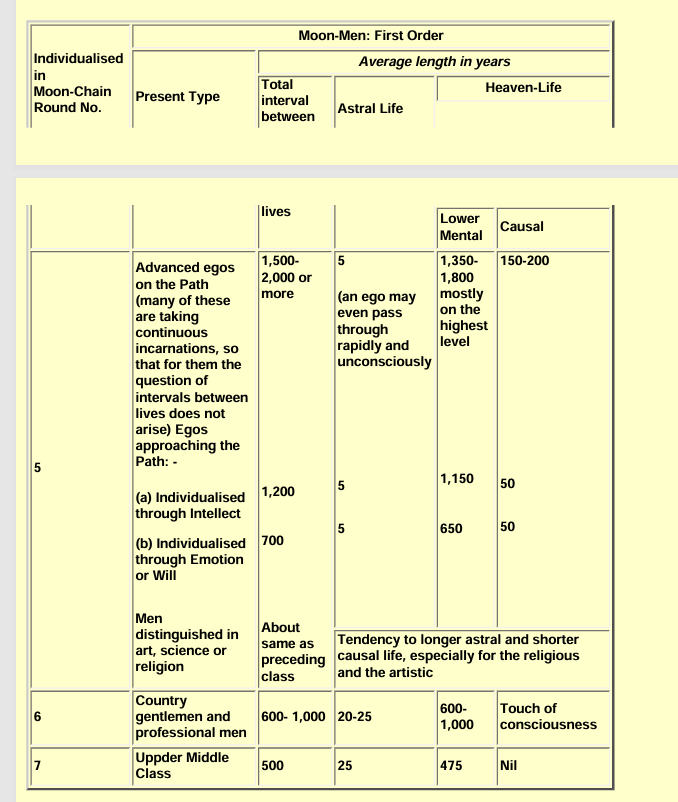

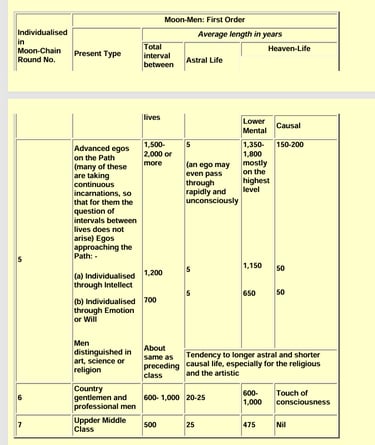

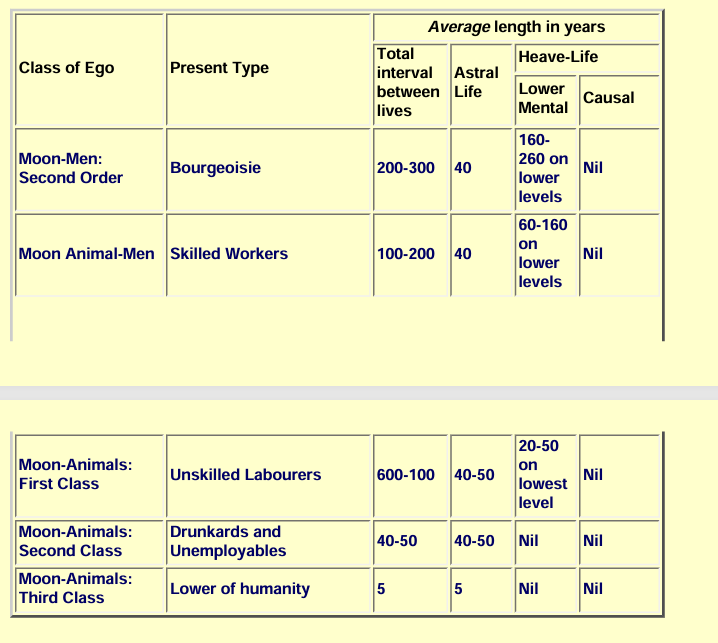

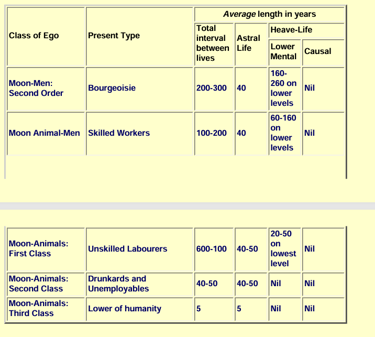

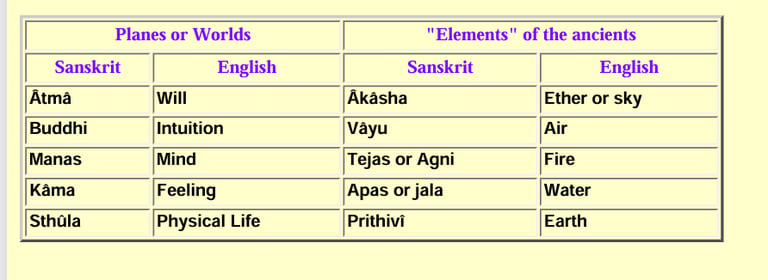

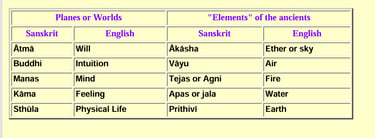

For convenience of reference these facts are set out in tabular form on page 146. The student may also like to have a brief enumeration of the Four States of Mind spoken of in Yoga. They are:

[1] Jagrat : waking consciousness

[2] Svapna : dream consciousness; consciousness working in the astral body and able to impress its experiences upon the brain.

[3] Sushupti : deep-sleep consciousness, working in the mental body, and not able to impress its experiences on the physical brain.

[4] Turiya : trance consciousness, so far separated from the brain that it cannot readily be recalled by outer means.

It is important to note, however, that these four states of consciousness exist on every plane. The following gives examples of the four states in physical consciousness, and is arranged in tabular form for the sake of compactness and clarity:

It should also be noted that the terms are relative; thus, for most people, Jagrat, or waking consciousness, is that part of the total consciousness which is functioning in the brain and nervous system, and which is definitely self-conscious. We may think of consciousness as a great egg of light, of which one end only is inserted into the brain; that end is the waking consciousness.

But, as self-consciousness is developed in the astral world, and the brain develops sufficiently to answer to its vibrations, astral consciousness becomes a part of the waking consciousness; the mental consciousness would then be the svapna, or dream-consciousness.

Similarly, when mental self-consciousness is developed, and the brain answers to it, the waking consciousness includes the mental. And so on, until all the consciousness on the five planes is included in the waking consciousness.

This enlarging of waking-consciousness involves development in the atoms of the brain as well as the development of certain organs in the brain, and of the connections between the cells.

For the inclusion of astral self-consciousness the pituitary body must be developed, and the fourth set of spirillae in the atoms must be perfected.

For the inclusion of mental self-consciousness the pineal gland must be active, and the fifth set of spirillae in thorough working order.

If these physical developments are not achieved, then the astral and mental consciousness remain super-consciousness, and are not expressed through the brain.

Again, if a man possesses no physical body, then his jagrat or waking consciousness is his astral consciousness. Thus a wider definition of jagrat would be that it is that part of the total consciousness which is working through its outermost vehicle.

We may also reconsider, from the point of view of the above analysis, Samadhi. Samadhi is a state of consciousness in which the body is insensible, but the mind is fully self-conscious, and from which the mind returns to the physical brain with the memory of its super-physical experiences.

If a man throws himself into a trance, and is active on the astral plane, then his Samadhi is on the astral. If he functions on the mental plane, then his Samadhi is on that plane.

The man who can practise Samadhi can thus withdraw from the physical body so as to leave it insensitive while his mind is fully conscious.

Samadhi is therefore a relative term. Thus a master begins His Samadhi on the plane of atma, and rises thence to the higher cosmic planes.

The word Samadhi is also sometimes used to denote the condition just beyond the level where a man can retain consciousness. Thus, for a savage whose consciousness is clear only on the physical plane, the astral plane would be Samadhi. It means that when the man comes back to his lower vehicles he would bring with him no definite additional knowledge and no new power of doing anything of use. This kind of Samadhi, is not encouraged in the highest schools of occultism.

Going to sleep and going into Samadhi are largely the same process ; but while one is due to ordinary conditions and has no significance, the other is due to the action of the trained will and is a priceless power.

Physical means of inducing trance, such as hypnotism, drugs, staring at a black spot on a white ground, or at the point of the nose, and other similar practices, belong to the method of Hatha Yoga, and are never employed in Raja Yoga.

To a clairvoyant, the difference between a mesmerised subject and the self-induced trance of a Yogi is at once apparent. In the mesmerised or hypnotised subject all the "principles" are present, the higher manas paralysed, buddhi severed from it through that paralysis, and the astral body entirely subjected to lower manas and kama.

In the yogi on the other hand, the "principles" of the lower quaternary disappear entirely, except for hardly perceptible vibrations of the golden-hued prana and a violet flame streaked with gold rushing upwards from the head and culminating in a point.

The mesmerised or hypnotised person recollects in his brain nothing of his experiences; the yogi remembers everything that has happened to him.

A few practical examples will perhaps best illustrate some of the methods employed in meditation.

The student will do well to commence by cultivating the thought, until it becomes habitual, that the physical body is an instrument of the spirit. He should think of the physical body, how it is possible to control and direct it, and then should separate himself in thought from it, repudiate it, in fact.

Next, perceiving that he can control his emotions and desires, he should repudiate the astral body, with its desires and emotions; then, picturing himself as in the mental body, and again reflecting that he can control and direct his thoughts, he should repudiate his mind, and should then let himself soar into the free atmosphere of the spirit where is eternal peace; resting there for a moment, let him strive with great intensity to realise that That is the real Self.

Descending again in consciousness, he should endeavour to carry with him the peace of the spirit into his different bodies.

Another exercise would be to direct the meditation to character-building, selecting for the purpose a virtue, let us say harmlessness. The attention having been concentrated, the subject is thought about in its many aspect; eg., harmlessness is act, in speech, in thought, in desire; how harmlessness would be expressed in the life of the ideal man; how it would affect his Daily life; how he would treat people if he had fully acquired the virtue, and so forth.

Having thus meditated upon harmlessness, he would carry with him into the daily life a state of mind that would soon express itself in all his action and thoughts. Other qualities could, of course, be similarly treated. A few months of earnest effort along these lines would produce wonderful changes in a man's life, as described in the memorable words of Plotinus. "Withdraw into yourself and look. And if you do not find yourself beautiful as yet, do as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful; he cuts away here, he smoothes there, he makes the line lighter, this other purer, until he has shown a beautiful face upon the statue. So do you also; cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is shadowed, labour to make all glow with beauty, and do not cease chiseling your statue until there shall shine out on you the godlike splendour of virtue, until you shall see the final goodness surely established in the stainless shrine". [Plotinus on the Beautiful, translated by Stephen Mackenna].

Meditation upon a virtue thus causes a man gradually to grow into the possession of that virtue ; as finely said in the Hindu Scriptures : "What a man thinks on, that he becomes; therefore think on the Eternal". And again : "Man is the creation of thought".

An excellent example of what may be done in this manner by meditation is that of a certain man who for forty years meditated daily upon truth; the effect was that he so tuned himself to the mode of truth that he always knew when a man was lying by the jar that he felt in himself. It so happened that the man was a judge, so that his faculty must have stood him in good stead.

In this work a man is employing his imagination – the great tool used in Yoga. If a man imagines in his thought that he has a certain quality, he is half way to possessing that quality; if he imagines himself free from a certain failing, he is half way to being free from that failing. So powerful a weapon is a trained imagination that a man may by its use rid himself of half his troubles and his faults.

It is not wise to brood over faults, as it tends to encourage morbidness and depression which act as a wall, shutting out spiritual influences. In practice it is better to ignore faults of disposition so far as may be done, and to concentrate on building the opposite virtues.

Success in the spiritual life is gained less by fierce wrestling with the lower nature than by growing into the knowledge and appreciation of higher things. For once we have sufficiently experienced the bliss and joyousness of the higher life, by contrast the lower desires pale and lose their attractiveness. It was said by a great Teacher that the best form of repentance for a transgression was to look ahead with hopeful courage, coupled with the firm resolve not to commit the transgression again.

Next, suppose the purpose of the meditation is to be intellectual understanding of an object, and the relation of it to other objects.

It is important for the student to recollect that the first work of the Knower is to observe –accurately, for on the accuracy of the observation depends the thought; if the observation is inaccurate, then out of that initial error will spring a number of consequent errors that nothing can put right save going back to the very beginning.

The object having thus been carefully observed, the stream of thought is played upon it so as to grasp it in all its natural, super-physical and metaphysical aspects, an effort being made to make quite clear and definite that level of the consciousness which is still nebular. Let the subject be, for example, harmony. Consider it in relation to the various senses; consider it in music, in colour, in phenomena of many different kinds; seek to discover the principal features of harmony, and how it differs from other similar and contrasting ideas; what part it plays in the succession of events; what is its use; what results from its absence. Having answered all these, and many other questions, an endeavour should be made to drop all concrete images or thoughts, and to hold in thought the abstract idea of harmony.

The student must bear in mind that mental sight is quite as real and satisfying as is physical sight. Thus it is possible to train the mind to see, say, the idea of harmony, or the square root of two, as clearly and as certainly as one sees a tree or a table with physical vision.

For our third example let us take a devotional meditation. Think of the ideal man, the Master, or, if preferred, the deity, or any manifestation of the deity. Allow the thought to play upon the subject from different aspects, so that it constantly awakens admiration, gratitude, reverence, worship. Ponder upon all the qualities manifested in the subject and take each quality in all its aspects and relationships.

From a general standpoint, an abstract ideal and a personality are equally good for purposes of meditation. A person of intellectual temperament will usually find the abstract ideal the more satisfactory; one of the emotional temperament will demand a concrete embodiment of his thought. The disadvantage of the abstract ideal is that it is apt to fail in compelling aspiration; the disadvantage of the concrete embodiment is that the embodiment is apt to fall below the ideal.

We may here take especial notice of the result of meditating on the Master, this makes a definite link with the Master ,which shows itself to the clairvoyant vision as a kind of line of light. The Master always subconsciously feels the impinging of such a line and sends out along it in response a steady stream of magnetism which continues to play long after the meditation is over.

If a picture is used for purposes of meditation, it may often be observed to change in expression. This is because the will can be trained to act directly upon physical matter, the actual physical particles being unquestionably affected by the power of strong sustained thought.

One other form of meditation may be given, viz., that of mantric meditation. A mantram is a definite succession of sounds arranged by an occultist in order to bring about certain definite results. Those sounds, repeated rhythmically over and over again in succession, synchronise the vibrations of the vehicles into unity with themselves. A mantram is thus a mechanical way of checking vibrations, or inducing the vibrations that are desired. Its efficacy depends upon what is known as sympathetic vibration [vide The Astral Body, pp. 157-8].

The more a mantram is repeated, the more powerful the result. Hence the value of repetition in Church formulae, and of the rosary, which enables the consciousness to be fully concentrated on what is being said and thought, undistracted by the task of keeping count.

In this method of meditation, practised largely in India, the devotee directs his mind, say, to Shri Krishna, the incarnate God, the Spirit of Love and Knowledge in the world. A sentence is taken and chanted over and over again as a mantram, while its deep and varied meaning is intently pondered upon. Thus the devotee brings himself in touch with the Great Lord Himself.

The above constitutes the briefest outline of certain forms of meditation. For further description and detail the student is referred to that excellent manual Concentration by Ernest Wood, to

Meditation For Beginners by J.I. Wedgwood, and to the admirable chapters on ThoughtControl and on Building of Character in The Outer Court, by Dr. Besant.

An excellent "Ego Meditation" is given in Gods In Exile, by J.J. van der Leeuw, LL.D., in the Afterword at the end of that admirable little book.

Many people meditate daily alone, with success; but there are even greater possibilities when a group of people concentrate their minds on the one thing. That sets up a strain in the physical ether as well as in the astral and mental worlds, and it is a twist in the direction which we desire. Thus, instead of having to fight against our surroundings, as is usually the case, we find them actually helpful, provided of course, that all present succeed in holding their minds from wandering. A wandering mind in such a group constitutes a break in the current, so that instead of there being a huge mass of thought moving in one mighty flood, there would be eddies in it, like rocks which deflect the water in a river.

A striking example of the tremendous power of collective meditation and thought was that of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. C.W.Leadbeater describes that occasion as one of the most wonderful manifestations of occult force that he ever saw. The crowd became so exalted that people were lifted right out of themselves by their emotions, thus experiencing a tremendous uplift of soul. A similar effect, on a small scale, can be produced by group meditation.

We will now consider the physical adjuncts of meditation. In meditation, posture is not unimportant. The body should be put into a comfortable position, and then forgotten. If it is uncomfortable, it cannot be forgotten, as it would constantly call attention to itself.

Furthermore, just as certain thoughts and emotions tend to express themselves in characteristic movements and gestures of the body, so, by a reversal of the process, positions of the body may tend to induce states of mind and feeling, and so assist the student in dwelling on them.

The majority of Western people will find it most comfortable to sit in an armchair, the back of which does not slope unduly; the hands may be clasped and rest on the legs, or be laid lightly on the knees. The feet may be placed together or crossed with the right over the left. This locking of the extremities of the body helps to prevent the outflow of magnetism from the fingertips, feet, etc. The position should be easy and relaxed, the head not sunken upon the chest but lightly balanced; the eyes and mouth closed, the spinal column [along which there is much magnetic flow] erect.

Eastern people usually sit cross-legged on the floor or a low stool, a position which is said to be slightly more effectual since any magnetism liberated tends to rise around the body in a protective shell.

Another factor to be considered in determining the posture for meditation is the possibility of losing physical consciousness. The Indian who is sitting on the floor simply falls backwards without hurting the body; those who meditate in a chair will do well to make use of an armchair so that, in the event of the body losing consciousness, they may not fall out of it.

Except in very rare cases the lying-down position should not be adopted, on account of its natural tendency towards sleep.

A cold bath or a brisk walk beforehand is useful in order to overcome any tendency to sluggish circulation of the blood, which is obviously detrimental to brain activity.

There is an intimate connection between profound meditation and breathing. It is found in practice that as the body becomes harmonised in meditation the breathing grows deeper, regular and rhythmic, until by degrees it becomes so slow and quiet as to be almost imperceptible. Hatha Yoga reverses the process, and by deliberate regulation of the breathing seeks to harmonise the functions of the body, and finally, the workings of the mind.

The student, however, should be warned against the indiscriminate practice of breathing exercises; he will be far better advised to learn to control of thought along the lines of Raja Yoga , leaving his efforts at meditation to work their natural effect on the physical body.

Whilst some breathing exercises are exceedingly dangerous, there is no objection to simple, deep breathing provided undue strain is not placed upon the heart and lungs, and no attempt is made to concentrate the thought on the various centres, or chakrams, of the body. Good incense is also helpful, as it tends to purify the "atmosphere" from the occult standpoint. The student may also gain assistance from beautiful colours, flowers and pictures in his surroundings, and other means of uplifting the mind and feelings.

He will also find it useful to observe certain dietetic restrictions [vide The Astral Body. p. 65] and, if it can be done without detriment to health, to abstain from flesh-food and alcohol.

If alcohol is taken, meditation is apt to set up inflammatory symptoms in the brain affecting particularly the pituitary body [vide The Astral Body, p. 66].

Early morning is probably the most suitable time for meditation because desires and emotions are usually more tranquil after sleep and before the man plunges into the bustle of the world.

But whatever time is chosen it should be when there is assurance of being undisturbed.

Moreover, as already pointed out, it should always be at the same time, for regularity is of the essence of the prescription.

The times selected by ancient devotees were sunrise, noon and sunset, these being magnetically the most suitable. It is well to cultivate the habit of turning the mind for a moment at the stroke of every hour during the day to the realisation of oneself as the Spiritual Man.

This practice leads to what Christian Mystics called "self-recollectedness", and helps the student to train his mind to revert automatically to spiritual thoughts.

It is not well to meditate immediately after a meal, for the obvious reason that it tends to draw blood away from the digestive organs; neither is meditation at night good, because the bodies are tired and the etheric double is more readily displaceable; in addition, the negative influence of the moon is then operative, so that undesirable results are more liable to occur.

Sometimes meditation may be less successful than usual because of unfavourable astral or mental influences.

It is stated also by some people that at certain times the planetary influences are more favourable than at others. Thus an astrologer has said that when Jupiter had certain relations with the moon this had the effect of expanding the etheric atmosphere and making meditation appear more successful. Certain aspects with Saturn, on the other hand, were said to congest the etheric atmosphere, making meditation difficult.

The system of meditation briefly outlined above has as its object spiritual, mental and ethical development, and control of the mind and feelings. It does not aim at developing psychic faculties "from below upwards"; but its natural result may be to open up a form of intuitive psychism in persons of sufficiently sensitive organisation, which will show itself in increasing sensitiveness to the influence of people and places, in the recalling of fragmentary memories of astral plane experiences in sleep, in greater susceptibility to direct guidance from the ego, in the power to recognise the influence of the Masters and spiritually developed people, and so forth.

Meditation may result in illumination, which may be one of three quite different things:

[1] By intense and careful thinking over a subject a man may himself arrive at some conclusion with respect to it;

[2] he may obtain illumination from his higher self, discovering what his ego really thinks on his own plane about the question;

[3] he may, if highly developed, come into touch with Masters or devas. It is in [1] only that his conclusions would be likely to be vitiated by his own thought-forms; the higher self would be able to transcend these, and so would a Master or a deva.

What we can do in meditation depends upon what we are doing all day long. If we have prejudices, for example, in ordinary life, we cannot escape from them in meditation.

Physical meditation is, of course, for the training of the lower vehicles, not for the ego. During meditation the ego regards the personality much as at any other time –he is usually slightly contemptuous.

If the ego is at all developed he will meditate upon his own level, but that meditation need not, of course, synchronise with that of the personality.

Meditation is one means of acquiring the art of leaving the body in full consciousness. The consciousness being braced up to an unswerving steadiness and fixity, the attention is gradually withdrawn from the outer world and the body, the senses remaining quiet –[page 158]—while the mind is intensely alive, but with all its energies drawn inwards ready to be launched at a single point of thought, the highest to which it can attain. When it is able to hold itself thus with comparative ease by a strong but calm effort of will, it can throw itself beyond the highest thought it can reach while working in the physical brain, and in that effort will rise to, and unite itself with, the higher consciousness and find itself free from the body. When this is done there is no sense of sleep or dream nor any loss of consciousness; the man finds himself outside his body, as though he had slipped off a weighty encumbrance, not as though he had lost any part of himself.

There are other ways of obtaining freedom from the body; for example, by the rapt intensity of devotion, or by special methods that may be imparted by a great teacher to his pupil.

The man can return to his body and re-enter it at will; also, under these circumstances he can impress on the brain, and thus retain while in the physical body, the memory of the experiences he has undergone.

Real meditation means a strenuous effort, not the sensation of happiness which arises from a state of semi-somnolence and bodily luxury. It has, therefore, nothing to do with, and, in fact, is quite different from, the kind of passive mediumship developed in spiritualism.

The student need not be puzzled by the injunction that he should open himself to spiritual influences and at the same time be positive. Positive effort is needed as a preliminary; this uplifts the consciousness the higher levels so that the higher influences can play down; then, and only then, is it safe to relax the upward striving in the realisation of the peace thus attained. The phrase "opening oneself to spiritual influences" may be taken to mean maintaining an attitude of intense stillness at a high spiritual level, much as a bird, though seemingly passive and immobile, poises itself against the gale by a powerful effort continuously maintained in wing and pinion.

CHAPTER XVII

CONTEMPLATION

CONTEMPLATION is the third of the three stages, of which we have already considered two.

The three are :

[1] Concentration –The riveting of the attention on an object.

[2] Meditation –The stirring of the consciousness into activity with reference to that object alone; looking at the object in every possible light, and trying to penetrate its meaning, to reach a new and deep thought or receive some intuitional light upon it.

[3] Contemplation –The active centring of the consciousness on the object, while the lower activities of the consciousness are successfully repressed; the fixation of the attention for a time on the light received. It has been defined as concentration at the top of the line of thought or meditation.

In the Hindu terminology the stages are amplified and named as follows:

[1] Prâtyâhara : the preliminary stage, embracing entire control of the senses.

[2] Dhâranâ : concentration.

[3] Dhyâna : meditation.

[4] Samadhi : contemplation.

Dhâranâ, Dhyâna and Samadhi are known collectively as Sannyama. In meditation we discover what the object is as compared with other things, and in relation to them. We go on with this process of reasoning and argument until we can reason and argue no more about a object: then we suppress the process, stopping all comparing and arguing, with the attention fixed actively upon the object, trying to penetrate the indefiniteness which for us appears to surround it. That is contemplation.

The beginner should bear in mind that meditation is a science of a lifetime, so that he should not expect to attain to the stage of pure contemplation in his earlier efforts.

Contemplation may be described also as keeping the consciousness on one thing and drawing it into oneself so that the thinker and it become one.

When a well-trained mind can maintain its one-pointedness or concentration for some time, and can then drop the object, maintaining the fixed attention, but without the attention being directed to anything, then the stage of contemplation is reached.

In this stage the mental body shows no image; its own materials are held steady and firm, receiving no impressions, perfectly calm, like still water. This state cannot last for more than a very brief period, being like the "critical" state of the chemist, the point between two states of matter.

Expressed in another way, as the mental body is stilled, the consciousness escapes from it and passes into and out of the "laya centre", the neutral points of contact between the mental and the causal body.

This passage is accompanied by a momentary swoon, or loss of consciousness, the inevitable result of the disappearance of objects of consciousness, followed by consciousness in the higher body. The dropping out of objects of consciousness belonging to the lower worlds is thus followed by the appearance of objects of consciousness in the higher world.

Then the ego can shape the mental body according to his own lofty thoughts, and permeate it with his own vibrations. He can mould it after the visions he has obtained of planes even higher than his own, and can thus convey to the lower consciousness ideas to which the mental body would otherwise be unable to respond.

These are the inspirations of genius, that flash down into the mind with dazzling light and illuminate a world. The very man himself who gives them to the world can scarcely tell, in his ordinary mental state, how they have reached him ; but he knows that in some strange way----- "the power within me pealing Lives on my lip and beckons with my hand ".

Of this nature also are the ecstasy and visions of Saints, of all creeds and in all ages; in these cases, prolonged and absorbing prayer, or contemplation, has produced the necessary braincondition. The avenues of the senses have become closed by the intensity of the inner concentration, and the same state is reached, spasmodically and involuntarily, which the Raja Yogi seeks deliberately to attain.

The transition from meditation to contemplation has been described as passing from meditation "with seed" to meditation "without seed". Having steadied the mind, it is held poised on the highest point of the reasoning, the last link in the chain of argument, or on the central thought or figure of the whole process; that is meditation with seed.

Then the student should let everything go, but still keeping the mind in the position gained, the highest point reached, vigorous and alert. That is meditation without seed. Remaining poised, waiting in the silence and the void, the man is in the "cloud". Then suddenly there will be a change, a change unmistakable, stupendous, incredible. This is contemplation leading to illumination.

Thus, for example, practising contemplation on the ideal man, on a Master, having formed an image of the Master, the student contemplates it with ecstasy, filling himself with its glory and its beauty, and then straining upwards towards Him, he endeavours to raise his consciousness to the ideal, to merge himself in it, to become one with it.

The momentary swoon mentioned above is called in Sanskrit the Dharma-Megha, the cloud of righteousness ; Western mystics speak of it as the "Cloud on the Mount", the "Cloud on the Sanctuary", the "Cloud on the Mercy-Seat". The man feels as though surrounded by a dense mist, conscious that he is not alone, but unable to see. Presently the cloud thins, and the consciousness of the higher plane dawns. But before it does so it seems to the man that his very life is draining away, that he is hanging in the void of great darkness unspeakably lonely.

But "Be still, and know that I am God". In that silence and stillness the Voice of the Self shall be heard, the glory of the Self shall be seen. The cloud vanishes and the Self is made manifest.

Before it is possible to pass from meditation to contemplation, wishing and hoping must be entirely given up, at least during the period of practice : in other words, Kâma must be perfectly under control. The mind can never be single while wishes occupy it; every wish is a seed from which may spring anger, untruthfulness, impurity, resentment, greed, carelessness, discontent, sloth, ignorance etc. While one wish of hope remains, these violations of the law are possible.

So long as there are wishes, non-satisfactions, they will call one aside ; the stream of thought is ever seeking to flow aside into little gullies and channels left open by unsatisfied desires and indecisive thought.

Every unsatisfied desire, every un-thought-out problem, will present a hungry mouth ever calling aside the attention ; when the train of thought meets a difficulty it will swing aside to attend to these calls. Tracing out interrupted chains of thought, it will be found that they have their source in unsatisfied desires and unsettled problems.

The process of contemplation commences when the conscious activity begins to run, as it were, at right angles to the usual activity, which endeavours to understand a thing in reference to other things of its own nature and plane ; such movement cuts across the planes of its existence and penetrates into its subtler inner nature. When the attention is no longer divided into parts by the activities of comparing, the mind will move as a whole, and will seem quite still, just as a spinning top may appear to stand still when it is in most rapid motion.

In contemplation one no longer thinks about the object, it is better even not to start with any idea of the self and the object as two different things in relation to one another, because to do so will tend to colour the idea with feeling. The endeavour should be made to reach such a point of self-detachment that the contemplation can start from inside the object itself, the mental enthusiasm and energy being at the same time kept up all along the line of thought.

The consciousness is to be held, poised like a bird on the wing, looking forward and never thinking of turning back.

In contemplation the thought is carried inwards until it can go no further ; it is held in that position without going back or turning aside, knowing that there is something there, although it is unable to grasp clearly what it is. In this contemplation there is, of course nothing in the nature of sleep or mental activity, but an intense search, a prolonged effort to see in the indefiniteness something definite, without descending to the ordinary lower regions of conscious activity in which the vision is normally clear and precise.

A devotee would practise contemplation in a similar manner, but in his case the activity would be mainly feeling rather than thought.

In contemplation on his own nature, the student repudiates his identity with the outer bodies and with the mind. In this process he is not divesting himself of attributes, but of limitations.

The mind is swifter and freer than the body, and beyond the mind is spirit, which is freer and swifter still. Love is more possible in the quietude of the heart than in any outer expression, but in the spirit beyond the mind it is divinely certain. Reason and judgement ever correct the halting evidence of the senses ; the vision of the spirit discerns the truth without organs and without mind.

The key to success at every step of these practices may be stated thus: obstruct the lower activities, while maintaining the full flow of conscious energy. First, the lower mind must be made vigorous and alert; then its activity must be obstructed while the impetus gained is used to exercise and develop the higher faculties within.

An ancient science of Yoga teaches, when the processes of the thinking mind are repressed by the active will, the man finds himself in a new state of consciousness which transcends the ordinary thinking and governs it, just as thought transcends and selects among desires, and just as desires prompt to particular actions and efforts. Such a superior state of consciousness cannot be described in terms of the lower mind, but its attainment means that the man is conscious that he is something above mind and thought even though mental activity may be going on, just as all cultured people recognise that they are not the physical body, even when that body may be acting.

There is thus another state of existence, or rather another living conception of life, beyond the mind with its laboured processes of discernment, of comparisons and causal relations between things. That higher state is to be realised only when the activities of consciousness are carried, in all their earthly fervour and vigour, beyond the groping cave-life in which they normally dwell.

That higher consciousness will come to all men sooner or later; and when it comes all life will suddenly appear changed.

As the student by his meditation grows richer in spiritual experience, he will thus find new phases of consciousness gradually opening up within him. Fixed in aspiration upon his ideal, he will presently become aware of the influence of that ideal raying down upon him, and as he makes a desperate effort to reach the object of his devotion, for a brief moment the floodgates of heaven itself will be opened and he will find himself made one with his ideal and suffused with the glory of its realisation. Having transcended the more formal figures of the mind, an intense effort is made to reach upwards. Then will come the attainment of that state of ecstasy of spirit, when the limits of the personality have fallen away and all shadow of separateness has vanished in the perfect union of object and seeker.

As said in The Voice of The Silence : "Thou canst not travel on the Path before thou hast become that Path itself…Behold ! thou hast become the light, thou hast become the sound, thou art thy Master and thy God. Thou art thyself the object of thy search; the voice unbroken, that resounds throughout eternities, exempt from change, from sin exempt, the seven sounds in one."

It were idle to attempt further description of such experiences, for they are beyond the reach of formulated utterance. Words serve but as signposts pointing out the way to that which is ineffably glorious, so that the pilgrim may know whither to direct his steps.

CHAPTER XVIII

SLEEP-LIFE

Many people find themselves troubled with streams of wandering thought when they are trying to fall asleep. In such cases a mental shell will deliver them from such of these thoughts as come from without. Such a shell need only be temporary, since all that is required is peace for an interval sufficient to allow the man to fall asleep.

The man will carry away with him this mental shell when he leaves his physical body, but its work will then be accomplished, its sole object being to enable him to leave his body.

Whilst he was in the physical body, the mental action on the brain particles may easily have prevented him quitting the body; but when once he is away from the body the same worry or wandering thought will not bring him back to it.

When the shell breaks up, the stream of idle thoughts or mental worry will probably re-assert itself, but as the man will be away from his physical brain this will not interfere with the repose of the body.

It is an extremely rare occurrence for either an ordinary person during sleep, or a psychically developed person in trance condition, to penetrate to the mental plane. Purity of life and purpose would be an absolute pre-requisite, and even when the mental plane was reached there would be nothing that could be called real consciousness, but simply a capacity for receiving impressions.

An example showing the possibility of entering the mental plane during sleep may be given. A person of pure mind and considerable though untrained psychic capacity was approached during sleep, and a thought-picture was presented to her mind. So intense was the feeling of reverent joy, so lofty and so spiritual were the thoughts evoked by the contemplation of the glorious scene that the consciousness of the sleeper passed into the mental body, i.e.,, she rose" to the mental plane. Although she was floating in the sea of light and colour, nevertheless she was entirely absorbed in her own thought, and conscious of nothing beyond it. She remained in that condition for several hours, though apparently unconscious of the passage of time. It is clear in this case, that although the sleeper was conscious on the mental plane, yet she was by no means conscious of it.

It seems probable that a result such as this would be possible only in the case of a person having already some amount of psychic development; the same condition is even more definitely necessary in order that a mesmerised subject could touch the mental plane in trance.

The reason for this, as previously stated, is that in the average man the mental body is not sufficiently developed to be employed as a separate vehicle of consciousness. It can, in fact, be employed as a vehicle only by those who have been specially trained in its use by teachers belonging to the Great Brotherhood of Initiates.

We may repeat here what was said in Chapter XVI, viz., that up to the time of the First Initiation, a man works at night in his astral body; but as soon as it is perfectly under control, and he is able to use it fully, work in the mental body is begun. When this body in turn is completely organised, it is a far more flexible vehicle than the astral body, and much that is impossible on the astral plane can be accomplished therein.

Although a man after death may live in the heaven world, i.e., on the mental plane [as we shall see in later chapters], yet he is shut up in a shell of his own thoughts; this cannot be called functioning on the mental plane, for that involves the ability to move about freely on that plane, and to observe what exists there.

A man who is able to function freely in the mental body has the capacity of entering upon all the glory and beauty of the mental plane, and possesses, even when working on the astral plane, the far more comprehensive mental sense, which opens up to him such marvellous vistas of knowledge, and practically renders error all but impossible.

When functioning in the mental body, a man leaves his astral body behind him along with the physical body; if he wishes to show himself upon the astral plane for any reason, he does not send for his own astral vehicle, but by a single action of his will materialises one for his temporary need. Such an astral materialisation is called a mâyâvirûpa, and to form it for the first time usually needs the assistance of a qualified master. [This subject will be dealt with in our next chapter].

There is another way in which the sleep-life can be usefully employed, viz., for solving problems. The method is, of course, practised by many people, though for the most part unconsciously; it is expressed in the proverb that "The night brings counsel". The problem to be solved should be quietly held in the mind when going to sleep; it should not be debated or argued, or sleep may be prevented; it should be merely stated to the mind and left. Then, when during sleep the Thinker is freed from the physical body and brain, he will take up the problem and deal with it. Usually the thinker will impress the solution on the brain so that it will be in the consciousness on awakening. It is a good plan to keep paper and pencil by the bed in order to note down the solution immediately on waking, because a thought thus obtained is very readily erased by the thronging stimuli from the physical world, and is not easily recovered.

CHAPTER XIX

THE MÂYÂVIRÛPA

MÂYÂVIRÛPA means literally "body of illusion". It is a temporary astral body made by one who is able to function in the mental body. It may, or may not, resemble the physical body, the form given to it being suitable to the purpose for which it is projected. It may be made, at will, visible or invisible on the physical plane; it can be made indistinguishable from a physical body, warm and firm to the touch, as well as visible, able to carry on a conversation, at all points like a physical being.

The advantage of using the MÂYÂVIRÛPA is that it is not subject to glamour on the astral plane, as is the astral body; no astral glamour can overpower the MÂYÂVIRÛPA, or astral illusion deceive it.

With the power to form the mayavirupa, a man is able to pass instantly from the mental plane to the astral and back, and to use at all times the greater power and keener sense on the mental plane; it is necessary to form the astral materialisation only when the man wishes to become visible to people in the astral world. When he has finished his work on the astral plane he withdraws to the mental plane again, and the mayavirupa vanishes, its materials returning to the general circulation of astral matter, whence they had been drawn by the pupil's will.

When in the MÂYÂVIRÛPA, a man may use the mental plane method of thought-transference so far as understanding another man is concerned; but, of course, the power of conveying the thought in that way to another is limited by the degree of development of that other man's astral body.

It is necessary that the Master shall first show His pupil how to make the MÂYÂVIRÛPA, after which, although it is not at first an easy matter, he can do it for himself.

After the Second Initiation, rapid progress is made with the development of the mental body, and it is at or near this point that the pupil learns to use the MÂYÂVIRÛPA.

CHAPTER XX

DEVACHAN : PRINCIPLES

The first portion of the life after death, spent on the astral plane, has already been fully described in The Astral Body. We therefore now take up our study from the moment when the astral body is left behind on its own plane, and the man withdraws his consciousness into the mental body, ie., "rises" to the mental plane, and in so doing enters what is known as the heaven-world. This is usually called by Theosophists Devachan, which means literally the Shining Land; it is also termed in Sanskrit Devasthân, the land of the Gods; it is the Svarga of the Hindus, the Sukhavati of the Buddhists, the Heaven of the Zoroastrian, Christian and Mohammedan; it has been called also the "Nirvana " of the common people." The basic principle of devachan is that it is a world of thought.

A man in devachan is described as a devachanî. [The word Devachan is etymologically inaccurate, and therefore misleading. It has, however, become so firmly embedded in the Theosophical terminology that the present compiler has retained it throughout this volume. At

least it has the merit of being less clumsy than "heaven-world" –A. E. Powell.]

In the older books devachan is described as a specially guarded part of the mental plane, where all sorrow and evil are excluded by the action of the great spiritual Intelligences who superintend human evolution. It is the blissful resting-place of man where he peacefully assimilates the fruits of his physical life.

In reality, however, devachan is not a reserved part of the mental plane. It is rather that each man, as we shall see presently, shuts himself up in his own shell, and therefore takes no part in the life of the mental plane at all; he does not move about freely and deal with people as he does on the astral plane.

Another way of regarding what has been called the artificial guardianship of devachan, the gulf that surrounds each individual there, arises from the fact that the whole of the kâmic, or astral, matter has, of course been swept away, and is no longer there. The man therefore has no vehicle, no medium of communication which can respond to anything in the lower worlds. For practical purposes these are in consequence non-existent for him.

The final separation of the mental body from the astral does not involve any pain or suffering; in fact, it is impossible that the ordinary man should in any way realise its nature; he would simply feel himself sinking gently into a delightful repose.

There is however, usually a period of blank unconsciousness, analogous to that which usually follows physical death; the period may vary within wide limits, and from it the man awakens gradually.

It appears that this period of unconsciousness is one of gestation, corresponding to the pre-natal physical life, and being necessary for the building up of the devachanic ego for the life in devachan. Part of it appears to be occupied in the absorption by the astral permanent atom of everything that has to be carried forward for the future, and part of it in vivifying the matter of the mental body for its coming separate independent life.

When the man awakens again, after the second death, his first sense is one of indescribable bliss and vitality, a feeling of such other joy in living that he needs for the time nothing but just to live. Such bliss is of the essence of life in all the higher worlds of the system. Even astral life has possibilities of happiness far greater than anything that we can know in the physical life, but the heaven-life is out of all proportion more blissful than the astral. In each higher world the same experience is repeated, each far surpassing the preceding one. This is true not only of the feeling of bliss, but also of wisdom and breadth of view. The heaven life is so much fuller and wider than the astral that no comparison between them is possible.

As the sleeper awakens in devachan the most delicate hues greet his opening eyes, the very air seems music and colour, the whole being is suffused with light and harmony. Then through the golden haze appear the faces of those he has loved on earth, etherealised into the beauty which expresses their noblest, loveliest emotions, unmarred by the troubles and the passions of the lower worlds. No man may describe adequately the bliss of the awakening into the heaven-world.

This intensity of bliss is the main characteristic of the heaven-life. It is not merely that evil and sorrow are in the nature of things impossible in that world, or even that every creature is happy there. It is a world in which every being must, from the very fact of his presence there, be enjoying the highest spiritual bliss of which he is capable, a world where power of response to his aspirations is limited only by his capacity to aspire.

This sense of the overwhelming presence of universal joy never leaves a man in devachan; nothing on earth is like it, nothing can image it; the tremendous spiritual vitality of this celestial world is indescribable.

Various attempts have been made to describe the heaven-world, but all of them fail because it is by its nature indescribable in physical language. Thus Buddhist and Hindu seers speak of trees of gold and silver with jewelled fruits; the Jewish scribe, having lived in a great and magnificent city, spoke of the streets of gold and silver; more modern Theosophical writers draw their similes from the colours of the sunset and the glories of the sea and sky.

Each alike tries to paint the truth, too grand for words, by employing such similes as are familiar to his mind.

The man's position in the mental world differs widely from that in the astral. In the astral he was using a body to which he was thoroughly accustomed, having been in the habit of using it during sleep. The mental vehicle however, he has never used before, and it is far from being fully developed. It thus shuts him out to a great extent from the world about him, instead of enabling him to see it.

During his purgatorial life on the astral plane the lower part of his nature burnt itself away; now there remain to him only his higher and more refined thoughts, the noble and unselfish aspirations which he entertained during his earth-life.

In the astral world he may have a comparatively pleasant life, though distinctly limited; on the other hand, he may suffer considerably in that purgatorial existence. But in devachan he reaps the results only of such of his thoughts and feelings as have been entirely unselfish; hence the devachanic life cannot be other than blissful.

As a Master has said, devachan "is the land where there are no tears, no sighs, where there is neither marrying nor giving in marriage, and where the just realise their full perfection."

The thoughts which cluster round the devachani make a sort of shell, through the medium of which he is able to respond to certain types of vibration in this refined matter. These thoughts are the powers by which he draws on the infinite wealth of the heaven-world. They serve as windows through which he can look out upon the glory and beauty of the heaven-world, and through which also response may come to him from forces without.

Every man who is above the lowest savage must have had some touch of pure unselfish feeling, even if it were but once in all his life; and that will be a window for him now.

It would be an error to regard this shell of thought as a limitation. Its function is not to shut a man off from the vibrations of the plane, but rather to enable him to respond to such influences as are within his capacity to cognise.

The mental plane [as we shall see in Chapter XXVII] is a reflection of the Divine Mind, a storehouse of infinite extent, from which the person enjoying heaven is able to draw just according to the power of his own thoughts and aspirations generated during his physical and astral life.

In the heaven-world these limitations –if we may call them that for the moment –no longer exist; but with that higher world we are not concerned in this volume.

Each man is able to draw upon the heaven-world, and to cognise only so much of it as he has by previous effort prepared himself to take. As the Eastern simile has it, each man brings his own cup; some of the cups are large, and some are small. But, large or small, every cup is filled to its uttermost capacity; the sea of bliss is far more than enough for all.

The ordinary man is not capable of any great activity in this mental world; his condition is chiefly receptive, and his vision of anything outside his own shell of thought is of the most limited character. His thoughts and aspirations being only along certain lines, he cannot suddenly form new ones; hence he perforce can profit little from the living forces which surround him, or from the mighty angelic inhabitants of the mental world, even though many of these readily respond to certain of man's aspirations.

Thus a man who, during earth-life, has chiefly regarded physical things, has made for himself but few Windows through which he may contact the world in which he finds himself. A man, however, whose interests lay in art, music or philosophy will find measureless enjoyment and unlimited instruction awaiting him, the extent to which he can benefit depending solely upon his own power of perception.

There is a large number of people whose only higher thoughts are those connected with affection and devotion. A man who loves another deeply, or feels strong devotion to a personal deity, makes a strong mental image of that friend, or of the deity, and inevitably takes that mental image with him into the mental world, because it is to that level of matter that it naturally belongs.

Now follows an important and interesting result. The love which forms and retains the image is a very powerful force, strong enough in fact to reach and to act upon the ego of the friend, which exists on the higher mental plane; for it is of course, the ego that is the real man loved, not the physical body which is so partial a representation of him. The ego of the friend, feeling the vibration, at once and eagerly responds to it, and pours himself into the thought-form which has been made for him. The man's friend is therefore truly present with him more vividly than ever before.

It makes no difference whatever whether the friend is what we call living or dead; this is because the appeal is made, not to the fragment of the friend which is sometimes imprisoned in a physical body, but to the man himself on his own true level. The ego always responds; so that one who has a hundred friends can simultaneously and fully respond to the affection of every one of them, for no number of representations of a lower level can exhaust the infinity of the ego. Hence a man can express himself in the "heavens" of an indefinite number of people.

Each man in his heaven-life thus has around him the vivified thought-forms of all the friends for whose company he wishes. Moreover, they are for him always their best, because he has himself made the thought-images through which they manifest.

In the limited physical world we are accustomed to thinking of our friend as only the limited manifestation which we know on the physical plane. In the heaven world, on the other hand, we are clearly much nearer to the reality in our friends than we ever were on earth, as we are two stages, or planes, nearer the home of the ego himself.

There is an important difference between life after death on the mental plane and life on the astral plane. For on the astral plane we meet our friends [during sleep of their physical bodies] in their astral bodies; i.e., we are still dealing with their personalities. On the mental plane, however, we do not meet our friends in the mental bodies which they use on earth. On the contrary, their egos build for themselves entirely new and separate mental vehicles and, instead of the consciousness of the personalities, the consciousness of the egos work through the mental vehicles. The mental plane activities of our friends are thus entirely separate in every way from the personalities of their physical lives.

Hence any sorrow or trouble which may fall upon the personality of the living man cannot in the least affect the thought-form of him which his ego is using as an additional mental body. If in that manifestation he did know of the sorrow or trouble of the personality, it would not be a trouble to him, because he would regard it from the point of view of the ego in the causal body, viz., as a lesson to be learned, or some karma to be worked out. In this view of is there is no delusion; on the contrary, it is the view of the lower personality which is the deluded one; for what the personality sees as troubles or sorrows are to the real man in the causal body merely steps on the upward path of evolution.

We also see that a man in devachan is not conscious of the personal lives of his friends on the physical plane.

What we may call the mechanical reason for this has already been fully explained. There are also other reasons, equally cogent, for this arrangement. For it would obviously be impossible for a man in devachan to be happy if he looked back and saw those whom he loved in sorrow and suffering, or in the commission of sin.

In devachan there is thus no separation due to space or time; nor can any misunderstanding of word or thought arise; on the contrary, there is a far closer communion, soul with soul, than ever was the case in earth-life. On the mental plane there is no barrier between soul and soul; exactly in proportion to the reality of soul-life in us is the reality of soul-communion in devachan. The soul of our friend lives in the form of him which we have created just to the extent that his soul and ours can throb in sympathetic vibration.

We can have no touch with those with whom on earth the ties were only of the physical and astral bodies, or if they and we were discordant in the inner life. Hence, in devachan no enemy can enter, for only sympathetic accord of mind and heart can draw men together in the heaven-world.

With those who are beyond us in evolution, we come into contact just so far as we can respond to them; with those who are less advanced than we are, we commune to the limit of their capacity.

The student will recollect that the Desire-Elemental re-arranges the astral body after death in concentric layers of matter, the densest outermost, thus confining the man to that sub-plane of the astral world to which belongs the matter in the outermost layer of his astral body. On the mental plane there is nothing to correspond to this, the mental elemental not acting in the manner adopted by the Desire-Elemental.

There is also another important difference between the astral and mental life. On the mental plane the man does not pass through the various levels in turn, but is drawn direct to the level which best corresponds to his degree of development. On that level he spends the whole of his life in the mental body. The varieties of that life are infinite, as each man makes his own for himself.

In devachan, the heaven world, all that was valuable in the moral and mental experiences of the Thinker during the life just ended is worked out, meditated over, and gradually transmuted into definite moral and mental faculty, into powers which he will take with him to his next incarnation. He does not work into the mental body, the actual memory of the past, for the mental body will, as we shall see in due course, disintegrate. The memory of the past abides only in the Thinker himself, who has lived through it and who endures. But the facts of past experience are worked into capacity, so that, if a man has studied deeply, the effects of that study will be the creation of a special faculty to acquire and master that subject when it is first presented to him in another incarnation. He will be born with a special aptitude for that line of study, and will absorb it with great facility.

Everything thought upon earth is thus utilised in devachan; every aspiration is worked up into power; all frustrated efforts become faculties and abilities; struggles and defeats re-appear as materials to be wrought into instruments of victory; sorrows and errors shine luminous as precious metals to be worked up into wise and well-directed volitions. Schemes of beneficence, for which power and skill to accomplish were lacking in the past, are in devachan worked out in thought, acted out, as it were, stage by stage, and the necessary power and skill are developed as faculties of mind to be put into use in a future life on earth.

In devachan, as a Master has said, the ego collects "only the nectar of moral qualities and consciousness from every terrestrial personality".

During the devachanic period the ego reviews his store of experiences, the harvest of the earth-life just closed, separating and classifying them, assimilating what is capable of assimilation, rejecting what is effete and useless.

The ego can no more be always busied in the whirl of earth-life than a workman can always be gathering store of materials, and never fabricating from them goods; or than a man can always be eating food and never digesting and assimilating it to build up the tissues of his body. Thus devachan, except for the very few, as we shall see later, is an absolute necessity in the scheme of things.

An imperfect understanding of the true nature of devachan has sometimes led people to think that the life of the ordinary person in the lower heaven-world is nothing but a dream and an illusion; that when he imagines himself happy amidst his family and friends, or carrying out his plans with such fullness of joy and success, he is really only a victim of a cruel delusion.

This idea results from misconception of what constitutes reality [so far as we can ever know it], and from a faulty point of view. The student should recollect that most people realise so little of their mental life, even as led in the body, that when they are presented with a picture of mental life out of the body, they lose all sense of reality, and feel as though they had passed into a world of dream. The truth is, however, that physical life compares unfavourably, as regards reality, with life in the mental world.

During ordinary earth-life it is obvious that that average person's conception of everything around him is imperfect and inaccurate in very many ways. He knows, for example, nothing of the etheric, astral and mental forces which lie behind everything he sees, and form in fact by far the most important part of it.

His whole outlook is limited to that small portion of things which his senses, his intellect, his education, his experience, enable him to take in. Thus he lives in a world very largely of his own creation. He does not realise that this is so, because he knows no better. Thus, from this point of view, ordinary physical life is at least as illusory as is life in devachan, and careful thought will show that it is really far more so.

For, when a man in devachan takes his thoughts to be real things, he is perfectly right; they are real things on the mental plane, because in that world nothing but thought can be real. The difference is that on the mental plane we recognise this great fact in nature, whereas on the physical plane we do not. Hence we are justified in saying that, of the two, the delusion is greater on the physical plane. Mental life, in fact, is far more intense, vivid, and nearer to reality than the life of the senses.

Hence, in the words of a Master: "we call the posthumous life the only reality, and the terrestrial one, including the personality itself, only imaginary." "To call the devachan existence a ‘dream' in any other sense than that of a conventional term, is to renounce for ever the knowledge of the Esoteric Doctrine, the sole custodian of truth".

One reason for the feeling of reality in earth-life, and of unreality when we hear of devachan, is that we look at earth-life from within, under the full sway of its illusions, while we contemplate devachan from outside free for the time from its particular grade of mâyâ or illusion.

In devachan itself the process is reversed; for its inhabitants feel their own life to be the real one, and look on earthlife as full of the most patent illusions and misconceptions. On the whole, those in devachan are nearer the truth than their physical critics in earth-life, but of course the illusions of earth, though lessened, are not wholly escaped from in the lower heavens, in spite of the fact that contact there is more real and more immediate.

In more general terms, the truth is that the higher we rise through the planes of being, the nearer we draw to reality; for spiritual things are relatively real and enduring, material things illusory and transitory.