THE MENTAL BODY , PART-5

THE MENTAL BODY , PART-5. THE AKASHIC RECORDS No description of the mental plane would be complete without an account of what are known as the Akashic Records. They constitute the only reliable history of the world, and are often spoken of as the memory of nature, also as the true Karmic Records,

GİZLİ ÖĞRETİLER

CHAPTER XXVIII

THE AKASHIC RECORDS

No description of the mental plane would be complete without an account of what are known as the Akashic Records. They constitute the only reliable history of the world, and are often spoken of as the memory of nature, also as the true Karmic Records, or the Book of the Lipika.

The word âkâshic is somewhat of a misnomer, for, though the records are read from the âkâsha, or matter of the mental plane, yet they do not really belong to that plane. A still worse name, which was often used in the earlier literature of the subject, was "records of the astral light", for they lie far beyond the astral plane, only broken glimpses of them being found on the astral plane, as we shall see presently. The word âkâshic is suitable only because it is on the mental plane that we first come definitely into contact with the records, and find it possible to do reliable work with them.

The student is already familiar with the fact that as a person develops, his causal body, which determines the limit of his aura, increases in size, as well as in luminosity and purity of colour. Pursuing this conception to an enormously higher level, we arrive at the idea that the Solar Logos comprehends within Himself the whole of our solar system. Hence anything that happens within our system is within the consciousness of the Logos. Thus we see that the true record is His memory. Furthermore, it is equally clear that on whatever plane that memory exists, it cannot but be far above anything that we know.

Consequently, whatever records we may find our selves able to read must be only a reflection of the great original, mirrored in the denser media of the lower planes. We know of these records on the buddhic, mental and astral planes, and we will describe them in the reverse order. On the astral plane the reflection is exceedingly imperfect; such records as can there be seen are fragmentary in the extreme, and often seriously distorted. The analogy of water, which is so often used as a symbol of the astral world is remarkably apt in this case. A clear reflection in still water is at best only a reflection, representing in two dimensions objects which are three-dimensional, and then showing only their shape and colour; also the objects are reversed. If the surface of the water be ruffled, the reflection is so broken and distorted as to be almost useless, and even misleading as a guide to the real shape and appearance of the objects reflected. Now on the astral plane we can never have anything approaching what corresponds to a still surface; on the contrary, we have to deal with one in rapid and bewildering motion. Hence we cannot depend upon getting a clear and definite reflection.

Thus a clairvoyant who possesses the faculty only of astral sight can never rely upon any picture of the past that comes before him as being accurate and perfect. Here and there some part of it may be so, but he has no means of knowing which it is. By long and careful training he may learn to distinguish between reliable and unreliable impressions, and to construct from broken reflections some kind of image of the object reflected. But usually long before he has mastered these difficulties he will have developed mental sight, which renders such labours unnecessary. On the mental plane, conditions are very different. There, the record is full and accurate; also it is impossible to make any mistake in reading.

That is to say, any number of clairvoyants, using mental sight, and examining a certain record, would see precisely the same reflection, and each would acquire a correct impression from reading it. With the faculties of the causal body the task of reading the records is still easier. It appears, in fact, that for perfection in reading-- [so far as that is possible on the mental plane]—the ego must be fully awakened, so that he can use the atomic matter of the mental plane. It is well known that if a number of persons witness a given event on the physical plane, their accounts afterwards will often vary considerably. This is because of faulty observation, each frequently seeing only those features of the event which most appealed to him.

This personal equation would not appreciably affect the impressions received in the case of an observation on the mental plane. For each observer would thoroughly grasp the entire subject, and so it would be impossible for him to see its parts out of due proportion. Error, however, may be easily occur in transferring the impressions received to the lower planes. The reasons for this we may group roughly as those due to the observer himself, and those due to the inherent difficulty, or rather impossibility, of performing the task perfectly. In the nature of things, only a small fraction of the experience on the mental plane could be expressed in physical worlds at all; hence, since all expression must be partial, there is obviously some possibility of choice in selecting the part expressed. For this reason, clairvoyant investigations by leading Theosophists are constantly checked and verified by more than one investigator, before they are published.

Apart from the personal equation, however, there are still the difficulties inherent in bringing impressions down from a higher to a lower plane. In order to understand this, the analogy of the art of painting is useful. A painter has to endeavour to reproduce a three-dimensional object on a flat surface, which of course has only two dimensions. Even the most perfect picture is in reality almost infinitely far from being a reproduction of the scene it represents: for hardly a single line or angle in it can ever be the same as those in the object copied.

It is simply a highly ingenious attempt to make upon one sense only, by means of lines and colours on a flat source, an impression similar to that which the actual scene depicted would make upon us. It can convey to us nothing, except by suggestion dependent on our own previous experience, of, for example, the roar of the sea, the scent of flowers, the taste of fruit, the hardness or softness of surfaces. Far greater are the difficulties experienced by a clairvoyant in endeavouring to express mental phenomena in physical plane language; for, as was mentioned in an earlier chapter, the mental world is five-dimensional. The appearance of the records varies to a certain extent, according to the conditions under which they are seen.

Upon the astral plane, the reflection is usually a simple picture, though occasionally the figure seen would be endowed with motion. In this case, instead of a mere snapshot, a rather longer and more perfect reflection has taken place. On the mental plane, they have two widely different aspects. First: if the observer is not thinking specially of them, the records simply form a background to whatever is going on. Under such conditions they are really merely reflections from the ceaseless activity of a great Consciousness upon a far higher plane, and have very much the appearance of cinematography pictures.

The action of the reflected figures constantly goes on, as though one were watching the actors on a distant stage. Second: if the trained observer turns his attention specially to any one scene, then, this being the plane of unhampered thought, it is instantly brought before him. Thus, if he wished to see the landing in Britain of Julius Caesar, in a moment he finds himself, not looking at a picture, but actually standing on the shore among the legionaries, with the whole scene being enacted around him, precisely as he would have seen it had he been there when it occurred in 55 BC. The actors are of course entirely unconscious of him, as they are but reflections, nor can any effort of his change the course of their action in any way.

But he has the power of controlling the rate at which the drama shall pass before him. He could thus have the events of a year take place before him in one hour. He could also stop the movement at any moment and hold any particular scene in view as long as he chooses. Not only does he see all that he would have seen physically, had he been present when the events occurred, but he hears and understands what the people say, and he is conscious of their thoughts and motives. There is one special case where an investigator can enter into an even closer sympathy with the records.

If he is observing a scene in which he himself took part in a previous life, there are two possibilities open to him.

[1] He may regard it in the usual manner, just as a spectator, though [as indicated above] a spectator whose insight and sympathy are perfect; or

[2] he may once more identify himself with that long-dead personality of his and experience over again the thought and emotions of that time.

He recovers, in fact, from the universal consciousness, that portion with which he has himself been associated.

The student will readily perceive the wonderful possibilities that open up before the man who is in full possession of the power to read the âkâshic records at will. He can review at leisure all history, correcting the many errors and misconceptions which have crept into the accounts handed down by historians. He can also watch, for example, the geological changes that have taken place, and the cataclysms which have altered the face of the earth many times. It is usually possible to determine the date of any record which may be examined, but it may require considerable pains and ingenuity.

There are many ways of doing this:

[1] The observer may look into the mind of an intelligent person present in the picture, and see what date he supposes it to be;

[2] he may observe the date, written in a letter or document. As soon as he has secured the date say according to the Roman or Grecian system of chronology, it is of course merely a matter of calculation to reduce it to the present accepted system.

[3] He may turn to some contemporary record, the date of which can easily be ascertained from ordinary historical sources. In comparatively recent times there is usually no great difficulty in ascertaining the date. But in much older times other methods have to be adopted. Even if the date can be read in the mind of someone living in the picture there may be difficulty in relating his system of dates to that of the observer. In such cases:

[4] the observer may run the records before him [which he can do at any speed, such as a year or a second, or faster if he chooses] and count the years from a date that is known. In such cases it is of course necessary to form some approximate idea, from the general appearance and surroundings, of the period, in order that he may not have too long a series of years to count.

[5] Where the years run into thousands, the above method would be too tedious to be practical. The observer, as an alternative, can notice the point in the heavens to which the axis of the earth is pointing, and calculate the date from the known data concerning that secondary rotation of the earth, known as the precession of the equinoxes.

[6] In extremely early records of events which took place millions of years ago, the period of the precession of the equinoxes [approximately 26,000 years] can be used as a unit. In these instances absolute accuracy is not required, hence the date in round numbers is sufficient for all practical purposes in dealing with such remote epochs. The accurate numbering of the records is possible only after careful training. As we have seen, mental sight is necessary before any reliable reading can be done.

In fact, to minimise the possibility of error, mental sight ought to be fully at the command of the investigator while awake in the physical body; and to obtain this years of labour and rigid self-discipline are necessary. Moreover, as the true records lie on a plane at present far beyond our ken, to comprehend them perfectly demands faculties of a far higher order than any which humanity has yet evolved. Hence our present view of the whole subject must necessarily be imperfect, because we are looking at it from below instead of from above.

The âkâshic records must not be confused with mere man-made thought-forms, which exist in such abundance on both the mental and astral planes. Thus for example, as we saw in Chapter VIII, any great historical event, having been constantly thought of, and vividly imaged by large numbers of people, exists as a definite thought-form on the mental plane. The same applies to characters in drama, fiction, etc. Such products of thought [ often be it noted, of quite ignorant or inaccurate thought] are much easier to see than the true âkâshic record, for, as we have said, to read the records requires training, whilst to see thought-forms needs nothing but a glimpse of the mental plane. Hence many visions of saints, seer, etc., are not of the true records but merely of thought-forms. One method of reading the records is by means of psychometry. It appears that there is a sort of magnetic attachment or affinity between any particle of matter and the record which contains history. Every particle, in fact, bears within it forever the impress of everything that has occurred in its neighbourhood. This affinity enables it to act as a kind of conductor between the record and the faculties of anyone who can read it.

The untrained clairvoyant usually cannot read the records without some such physical link to put him en rapport with the subject required. Such a method of exercising clairvoyance is psychometry. Thus, if a fragment of stone belonging, say, to Stonehenge, is given to a psychometer, he will see, and be able to describe, the ruins and the country surrounding them; in addition, he will probably also be able to see some of the past events with which Stonehenge was associated, such as Druidical ceremonies, for example. It is quite probable that ordinary memory is but another expression of the same principle. The scenes through which we pass in the course of our lives seem to act upon the cells of the brain in such a way as to establish a connection between those cells and the portion of the records with which we have been associated, and so we "remember" what we have seen.

Even a trained clairvoyant needs a link to enable him to find the record of an event of which he has no previous knowledge.

There are several way in which this may be done. Thus :

[1] if he has visited the scene of the event, he may call up the image of the spot, and then run through the records until he reaches the period desired.

[2] If he has not seen the place in question, he may run back in time to the date of the event and then search for what he wants;

[3] he may examine the records of the period, when he will have no difficulty in identifying any prominent person connected with the event; then he can run through the records of that person till he comes to the event for which he was looking.

We thus see that the power to read the memory of nature exists in men in many degrees; there are the few trained clairvoyants who can consult the records for themselves at will; the psychometer who needs an object connected with the past in order to bring him into touch with the past; the person who gets occasional, spasmodic glimpses of the past; the crystal-gazer who can sometimes direct his less certain astral telescope [see The Astral Body, p. 235] to some scene of long ago. Many of the lower manifestations of these powers are exercised unconsciously. Thus many a crystal-gazer watches scenes from the past, without being able to distinguish them from visions of the present; other vaguely psychic persons find pictures constantly arising before their eyes, without ever realising that they are actually psychometrising the various objects which happen to be around them.

A variant of this class of psychic is the man who is able to psychometrise persons only, instead of inanimate objects, as is more usual. In most cases this faculty shows itself erratically. Such psychics will sometimes, when they meet a stranger, see in a flash some prominent event in that stranger's life; on other occasions they will receive no special impression. More rarely are found persons who get detailed visions of the past life of everyone they encounter. One of the best examples of this class is probably that of the German Zschokke, who describes his remarkable faculty circumstantially in his autobiography. Although it is outside the scope of this book to treat of the buddhic plane, yet for the sake of completeness, and in this once instance, it may be well briefly to refer to the records as they exist on the buddhic plane.

The records, referred to as the memory of nature, are on the plane of buddhi very much more than a memory in the ordinary sense of the word. On this plane time and space are no longer limitations. The observer no longer needs to pass a series of events in review, for past and present, as well as future, are all alike and simultaneously present to him, for he is in what is called the "Eternal Now" –meaningless as such a phrase may sound on the physical plane. Infinitely below the consciousness of the Logos as even the buddhic plane is, it is abundantly clear that the "record: is not merely a memory; for all that has happened in the past, or that will happen in the future, is happening now before His eyes, just as much as are the events of what we call the present. Incredible as this may sound, it is nevertheless true. A simple and purely physical analogy may help to a partial understanding, not indeed of the future, but of the past and present being visible simultaneously.

Let the following two premises only be granted:

[1] That physical light can travel, at its usual speed, indefinitely into space without loss.

[2] That the Logos, being omnipresent, must be at every point in space, not successively, but simultaneously.

Granting these premises, it necessarily follows that everything which has ever happened, from the very beginning of the world, must at this very moment be taking place before the eyes of the Logos –not a mere memory of it, but the actual occurrence itself being now under His observation. Further, by a simple movement of consciousness through space, He would not only be continuously conscious of every event that had ever happened, but would also be conscious of every event happening, at any speed He chooses, either forwards [as we reckon time], or backwards. The illustration, however as stated, does not appear to throw any light on the problem of seeing the future, which for the present must remained unexplained, based, apart from metaphysical considerations, solely on the statements of those who have themselves been able to exercise, in some degree, the faculty of seeing future events.

The future cannot be seen as clearly as the past, for the faculty to see the future belongs to a still higher plane. Moreover, although prevision is to a great extent possible on the mental plane, yet it is not perfect, because wherever in the web of destiny the hand of the developed man comes in, his powerful will may introduce new threads, and change the pattern of the life to come. The course of the ordinary undeveloped man, who has practically no will of his own worth speaking of, may often be foreseen enough, but when the ego boldly takes his future into his own hands, exact prevision becomes impossible. A man who can use his atmic body can contact the Universal Memory beyond the limits even of his own Chain. On p.88 we mentioned one possible cause of plagiarism. Another cause, which sometimes occurs, is that two writers happening to see the same âkâshic record at the same time. In this case, they not only apparently plagiarise each other, but also, though each thinks himself the creator of a plot, a situation, etc., both are actually plagiarising the world's true history.

CHAPTER XXIX

MENTAL PLANE INHABITANTS

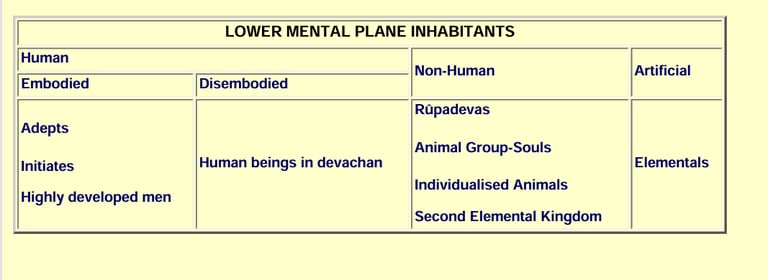

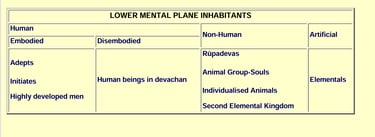

In classifying the inhabitants of the mental plane, we will adopt the classification chosen for the inhabitants of the astral plane [see The Astral Body, p. 168] viz. :

[1] Human,

[2] Non-Human,

[3] Artificial.

Since the products of man's evil passions, which bulk so largely the astral world, cannot exist on the mental plane, the sub-divisions we shall have to consider will naturally be far fewer than in the case of astral entities. The following table sets out the main classes:

It will be seen that Human entities are divided, for convenience, into embodied, i.e., those who are still attached to a physical body, "alive" as we say, and those who are "dead", who have no physical body. HUMAN : EMBODIED –Human beings who, while still attached to a physical body, are able to move in full consciousness and activity on the mental plane, are either Adepts or Their initiated pupils, for until a student has been taught by his Master how to use his mental body he will be unable to move with freedom upon even its lower levels. Adepts and Initiates appear as splendid globes of living colour, driving away all evil influence wherever they go, shedding around them a feeling of restfulness and happiness, of which even those who do not see them are often conscious.

It is in the mental world that much of their most important work is done, more especially upon the higher levels, where the individuality or ego can be acted upon directly. It is from this plane that they shower the grandest spiritual influences upon the world of thought. From it also they impel great and beneficent movements of all kinds.

Here also much of the spiritual force poured out by the self-sacrifice of the Nirmanakayas [see The Astral Body, p. 57] is distributed; here also direct teaching is given to those pupils who are sufficiently advanced to receive it in this way, since it can be imparted far more readily and completely here than on the astral plane. In addition, they have a great field of work in connection with those whom we call the "dead". Adepts or Masters for the most part reside on the highest or atomic level of the mental plane. But in the majority of cases, those who attain to the Asekha level, no longer retain either physical, astral, mental or causal bodies, but live permanently at Their highest level.

When They need to deal with a lower plane, They draw round Themselves a temporary vehicle of the matter belonging to that plane. In order the better to understand the conditions of the mental plane and its inhabitants, it is necessary to mention also those who are not present on the plane. The characteristics of the mental world being unselfishness and spirituality, it follows that the black magician and his pupils can find no place there. In spite of the fact that in many of them the intellect is very highly developed, and consequently the matter of their mental bodies is extremely active and sensitive along certain lines, yet in every case those lines are connected with personal desire of some sort.

They can find expression only through that lower part of the mental body, which is inextricably entangled with astral matter. As a necessary consequence of this limitation, their activities are practically confined to the astral and physical planes. A man whose whole life is evil and selfish, may indeed have periods of purely abstract thought during which he may utilise his mental body, provided he has learnt how to do so. But the moment that the personal element comes in, and the effort is made to produce some evil result, the thought is no longer abstract, and the man finds himself working in connection with the familiar astral matter once more.

One might therefore say that a black magician could function on the mental plane only while he forgot that he was a black magician. But even while he forgot it, he could be visible on the mental plane only to men functioning there consciously, never by any possibility to people in devachan, who are entirely secluded in a world of their own thoughts, into which nothing of an unpleasant or evil character can intrude from without. For ordinary people during sleep, or for psychically developed persons in trance, to penetrate to the mental plane, is just possible, though extremely rare. Purity of life and purpose would be an absolutely pre-requisite, and even when the plane was reached there would be nothing that could be called real consciousness, but simply a capacity for receiving certain impressions.

An example of this was given in the chapter on Sleep-Life, p. 166. HUMAN: DISEMBODIED –This class comprises all those in devachan, who have already been described in the chapters dealing with that condition. NON-HUMAN : -It was mentioned in The Astral Body, p. 169, that there are occasionally found on the astral plane certain cosmic entities, visitors from other planets and systems. Such visitors are very much more frequent on the mental plane. The difficulties of describing such entities in human language are almost insuperable, and the task will therefore not be attempted.

They are very lofty beings and are concerned, not with individuals, but with great cosmic processes. Those in touch with our world are the immediate agents for the carrying out of the law of karma, especially in connection with changes of land and sea brought about by earthquakes, tidal waves, and all other seismic causes. Rûpadevas :-The beings known to the Hindus and Buddhists as Devas, to Zoroastrians as the Lords of the heavenly and the earthly, to the Christians and Mohammedans as angels, and elsewhere as Sons of God, etc., are a kingdom of spirits belonging to an evolution distinct from that of humanity, an evolution in which they may be regarded as a kingdom next above humanity, much as humanity is next above the animal kingdom.

There is here however, an important difference; for, whilst an animal can pass only into the human kingdom, a human being, when he attains the Asekha level, has several choices, of which the deva line is one. Although connected with the earth, devas are by no means confined to it, for the whole of our chain of seven worlds is as one world to them, their evolution being through a grand system of seven chains. Their hosts have hitherto been recruited chiefly form other humanities in the solar system, some lower and some higher than ours, since but a very small portion of our own is sufficiently advanced to be able to join them. It seems certain that some of their very numerous classes have not passed through any humanity at al comparable with ours.

It is at present not possible for us to understand very much about them, but it is clear that the aim of their evolution is considerably higher than ours; that is to say, while the level of the Asekha Adept is that at which we are aiming at the end of the seventh round, the level attained by the deva evolution in the corresponding period will be a very much higher one. For them, as for us, there is a steeper, but shorter path leading to still more sublime heights.

There are at least as many types of angels or devas as there are races of men, and in each type there are many grades of power, of intellect, and of general development, so that altogether there are hundreds of varieties. Angels have been divided into nine Orders, the names used in the Christian Church being Angels, Archangels, Thrones, Dominations, Princedoms, Virtues, Powers, Cherubim and Seraphim. Of these, seven belong to the great Rays of which the solar system is composed, and two may be called cosmic, as they are common to some other systems. In each Order there are many types; in each there are some who work; some who assist those in trouble and sorrow; others who work among the vast hosts of the dead; some who guard, some who meditate, while others are at the stage where they are mainly concerned with their own development.

There are also angels of music, who express themselves in music as we express ourselves in words; to them an arpeggio is a greeting, a fugue a conversation, an oratorio an oration. There are angels of colour, who express themselves by kaleidoscopic changes of glowing hues. There are also angels who live in and express themselves by perfumes and fragrances. A sub-division of this type includes the angels of incense, who are drawn by its vibrations and find pleasure in utilising its possibilities. There is still another kind, belonging to the kingdom of nature-spirits or elves, who do not express themselves by means of perfumes, but who live by and on such emanations and so are always found where fragrance is disseminated.

There are may varieties, some feeding upon coarse and loathsome odours, and others only upon those which are delicate and refined. Amongst these are a few types who are especially attracted by the smell of incense, and who are therefore to be found in churches where incense is used. Those who have been taught to know and respond to the ancient call at the preface of the Christian Eucharist and who are charged with the distribution of the force, are often called the apostolic or messenger angels. Some of these are thoroughly conversant with this class of work, from long practice, others are novices, eagerly learning what has to be done, and how to do it.

The method of angelic evolution being largely by service, a ceremony such as the Eucharist offers them a remarkably good opportunity, of which they readily avail themselves. At a Low celebration, the Directing Angel first responds to the call sent out by the priest, and he seems to assemble the rest; at a High Celebration or Missa Cantata, the ancient melody attracts the notice of all immediately that it rings out, and they stand ready to attend at the appropriate time for each. The service rendered by the angels is of very many kinds, only a few bringing them into contact with human beings, mainly in connection with religious ceremonies. The angels invoked in the Christian services are far above men in spiritual development.

In Freemasonry also angelic aid is invoked, but those called upon are nearer to the level of men in development and intelligence, and each of them brings with him a number of subordinates, who carry out his directions. Every regularly constituted Masonic Lodge is in charge of a seventh-ray Angel, who directs its affairs. None of the devas have physical bodies such as we have. The lowest kind are called Kâmadevas, who have as their lowest body the astral; the next class is that of the Rûpadevas, who have bodies of lower mental matter, and who have their habitat on the four lower, or rûpa levels of the mental plane; the third class is that of the arûpadevas, who live in bodies of higher mental or causal matter. Above these there are four other great classes, inhabiting respectively the four higher planes of our solar system.

Above and beyond the deva kingdom altogether stand the great hosts of planetary spirits. In this book we are concerned, of course principally with the Rûpadevas. The relationship of devas to nature –spirits somewhat resembles, at a higher level, that of men to animals. Just as an animal can attain individualisation only by association with man, so it seems that a nature-spirit can normally acquire a permanent reincarnating individuality only by an attachment of a somewhat similar character to devas. Devas will never be human, most of them already byond that stage, but there are some who have been human beings in the past. The bodies of devas are more fluidic than those of men, being capable of far greater expansion and contraction. They have also a certain fiery quality which clearly distinguishes them from human beings.

The fluctuations in the aura of a deva are so great that, for example, the aura of one which was normally about 150 yards in diameter has been observed to expand to about two miles in diameter. The colours in the aura of a deva are more of the nature of flame than of cloud. A man looks like an exceedingly brilliant, yet delicate cloud of glowing gas, but a deva looks like a mass of fire. Devas live far more in the circumference, more all over their auras than a man does. Whilst 99 percent of the matter of a man's aura is within the periphery of his physical body, the proportion is far less in the case of a deva. They usually appear as human beings of gigantic size. They possess vast knowledge, great power, and are most splendid in appearance; they are described as radiant, flashing creatures, myriad-hued, like rainbows of changing supernal colours, of stateliest imperial mien, calm energy incarnate, embodiments of resistless strength. In Revelation [x. 1] one of them is described as having "a rainbow upon his head, and his face was as it were the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire".

"As the sound of many waters" are their voices. They guide natural order, their cohorts carrying on ceaselessly the process of nature with regularity and accuracy. Devas produce thought-forms as we do, but theirs are usually not so concrete as ours, until they reach a high level. They have a wide generalising nature, and are constantly making gorgeous plans. They have a colour language, which is probably not as definite as our speech, though in certain ways it may express more.

The Initiations which we take are not taken by devas; their kingdom and ours converge at a point higher than the Adept. There are ways in which a man can enter the deva evolution, even at our stage, or lower. The acceptance of this line of evolution is sometimes spoken of, in comparison with the sublime renunciation of the Nirmanakayas, as "yielding to the temptation to become a god". But it imust not be inferred from this expression that any shadow of blame attaches to the man who makes this choice.

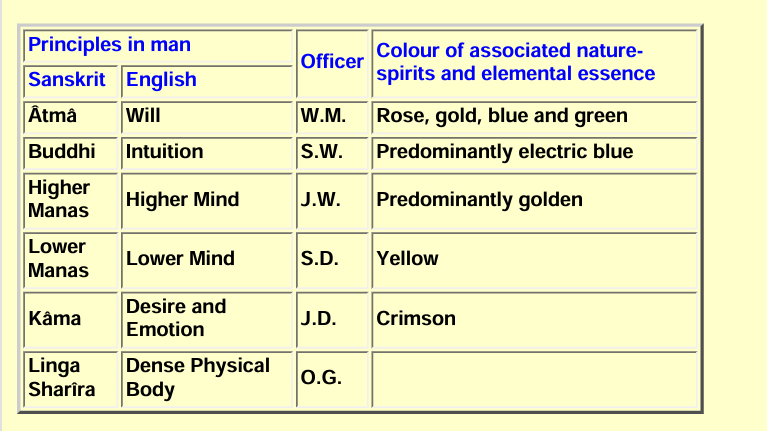

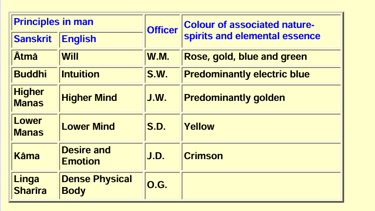

The Path which he selects is not the shortest, but it is a very noble one, and if his developed intuition impels him toward it, it is certainly the one best suited to his capacities. In Freemasonry the deva captain associated with the S.D. is a rûpadeva, and he employs nature-spirits and elemental essence at his own level. The deva captains corresponding to the three Principal Officers are arûpadevas, who possess the consciousness and wield the forces of the planes which they respectively represent. The deva of the J.W. takes charge of the 1st degree, the deva of the S.W. of the 2nd degree, and the deva of W. M. of the 3rd degree. Nothing is known of any rule or limit for the work of the devas.

They have more lines of activity than we can imagine. They are usually quite willing to expound and exemplify subjects along their own line to any human being who is sufficiently developed to appreciate them. Much instruction is given in this way, but few are able to profit by it as yet. Whilst devas are exceedingly beautiful, the lower orders of them have the vaguest and cloudiest conceptions of things, being inaccurate so far as facts are concerned. Hence, while a deva friend may be an exceedingly interesting person, yet, having no relation to the facts amidst which humanity is evolving, the greatest care should be exercised in following advice he may give as to physical actions.

In general, the higher order of devas unreservedly co-operate with the great Plan of the universe; hence the perfect "order" that we find in nature. In the lower ranks, this perfect obedience is instinctive and automatic, rather than conscious; they do their work, feeling impelled in the direction of the One Will which runs through everything. In the case of National devas, whilst the one at the head of each nation is a being of lofty intelligence, who always co-operates with the Plan, the lower national devas are found fighting, for example, for their own nation on a battlefield.

As their intelligence develops, they co-operate more and more with the Plan. The Spirit of the Earth, that obscure being who has the earth for his body, is not of the highest order of devas. Little is known of him; he may be said to belong more to the Rûpa Devas, because he has the earth for his body. Devas who are beyond the level of the Asekha Adept, i.e., that of the Fifth Initiation, normally live in what is called in Sanskrit the Jñânadeha, or the body of knowledge. The lowest part of that body is an atom of the nirvanic plane, serving them as our physical body serves us.

For a description of the four Devarâjas, or Regents of the Earth, the student is referred to The Astral Body, p. 187. In Freemasonry, the four tassels which appear in the corners of the "Indented Border" symbolise the Devarâjas, the Rulers of the elements of earth, water, air and fire, and the agents of the law of Karma. Animal Group-Souls . The group-souls, to which the vast majority of animals are attached, are found on the lower mental plane. It would take us too far afield to describe the nature of these group-souls, so we confine ourselves merely to mentioning them here. Individualised Animals. These, together with their state of consciousness on the mental plane, have already been described on p. 204

Second Elemental Kingdom. We have already, in Chapter II, described the genesis of the Mental Elemental Essence; we have also dealt with this essence in its function as part of man's mental body, and also as used in thought-forms. Little more, therefore, need be said about it here. There are three Elemental Kingdoms: the First ensouls matter of the higher mental or causal sub-planes; the Second, the matter of the four lower levels of the mental plane; the Third, astral matter. In the Second Kingdom, the highest subdivision exists on the fourth sub-plane, whilst there are two classes on each of the three lower sub planes, thus making in all seven subdivisions on these four sub-planes.

We have already seen [p.5] that the mental essence is on the downward arc of evolution, and therefore is less evolved than astral essence or, of course, than any of the later kingdoms, such as the mineral; and we have also emphasised the importance of this fact, which the student should bear constantly in mind. Mental Essence is, if possible, even more instantaneously sensitive to thought-action than is the astral Essence, the wonderful delicacy with which it responds to the faintest action of the mind being constantly and prominently brought to the notice of investigators.

It is, of course, in this response that its very life consists, its progress being helped by the use of it by thinking entities. If it could be imagined as entirely free for a moment from the action of thought, it would appear as a formless conglomeration of dancing infinitesimal atoms, instinct with marvellous intensity of life, but probably making but little progress on the downward path of evolution into matter. But when thought seizes upon it, and stirs it into activity, throwing it on the rûpa levels into all kinds of lovely forms [and on the arûpa levels into flashing streams], it receives a distinct additional impulse which, often repeated, helps it forward on its way.

For when a thought is directed from higher levels to the affairs of earth, it sweeps downwards and takes upon itself the matter of the lower planes. In doing this, it brings the elemental essence, of which the first veil was formed, into contact with that lower matter; thus by degrees the essence becomes accustomed to answer to lower vibrations, and so progresses in its downward evolution into matter. The Essence is also very noticeably affected by music, poured forth by great musicians in devachan [see p. 197]. It should be clearly recognised that there is a vast difference between the grandeur and power of thought on its own plane and the comparatively feeble effort we know as thought on the physical plane.

Ordinary thought originates in the mental body and, as it descends, clothes itself in astral essence. A man who can use his causal body generates his thoughts at that level; these thoughts clothe themselves in lower mental essence, and are consequently infinitely finer, more penetrating, and in every way more effective. If the thought be directed exclusively to higher objects, its vibrations may be too fine to find expression in astral matter; but when they do affect this lower matter they have far greater effect than those generated so much nearer to the level of that lower matter.

Following the idea further, the thought of an Initiate takes rise on the buddhic plane, and clothes itself in causal matter; the thought of a Master takes its rise on the plane of âtmâ, wielding the incalculable powers of regions of matter beyond our ordinary ken. ARTIFICIAL. Elementals. Mental elementals, or thought-forms, having already been fully described, little further need be said about them. The mental plane is even more fully peopled by artificial elementals than is the astral plane, and they play a large part among the living creatures that function on the mental plane. They are, of course, more radiant and more brilliantly coloured than are astral elementals, are stronger, more lasting, and more fully vitalised.

When it is also remembered how much grander and more powerful thought is on the mental plane, and that its forces are being wielded not only by human entities, but by devas, and by visitors from higher planes, it will be realised that the importance and influence of such artificial entities can scarcely be exaggerated. Great use is made of these mental elementals by Masters and Initiates, the elementals which they create having, of course, a much longer existence and proportionately greater power than any of those which were described in dealing with the astral plane, in The Astral Body, p. 190.

CHAPTER XXX

DEATH OF THE MENTAL BODY

Life in devachan, the heaven-world, being, as we have seen, finite, must come to an end. This takes place when the ego has assimilated all the essence of the experiences which were gathered in the preceding physical and astral lives. All the mental faculties, which were expressed through the mental body, are then withdrawn within the higher mental or causal body. Together with them, the mental unit, which performs a function similar to that performed by the physical and astral permanent atoms, also is withdrawn within the causal body, and remains there in a latent condition until called forth into renewed activity, when the time comes for re-birth.

The mental unit, together with the astral and physical permanent atoms, are enwrapped in the buddhic life-web [see p. 285], and stored up as a radiant nucleus-like particle in the causal body, being all that remains to the ego of his bodies in the lower worlds. The mental body itself, the last of the temporary vestures of the true man, the ego, is left behind as a mental corpse, just as the physical and astral bodies were left behind. Its materials disintegrate, and return to the general matter of the mental plane. We are not, strictly, concerned in this volume with the life of the man on the higher mental or causal plane, but, in order not to leave the story of man's life between one incarnation and the next too incomplete, we may mention very briefly the portion of that life spent on the higher mental plane. Every human being, on his completion of his life on the astral and lower mental planes, obtains at least a flash of consciousness of the ego, in the causal body. The more developed, of course, have a definitely conscious period, living as the ego on its own plane.

In the momentary flash of ego-consciousness, the man sees his last life as a whole, and gathers from it the impression of success or failure in the work which it was meant to do. Together with this, he also has a forecast of the life before him, with the knowledge of the general lesson which that is to teach, or the specific progress which he is intended to make in it. Only very slowly does the ego awaken to the value of these glimpses; but when he comes to understand them, he naturally begins to make use of them. Eventually he arrives at a stage when this glimpse is no longer momentary, when he is able to consider the question much more fully, and to devote some time to his plans for the life which lies before him. Further description of the life of the ego on his own plane must now be deferred for the fourth volume of this series, which will deal with The Causal Body.

CHAPTER XXXI

THE PERSONALITY AND EGO

We now come to consider the relationship between the personality and the ego. As, however, we have not yet studied the ego [this, of course, having to be reserved for our next volume on the Causal Body], it will not be possible for us to investigate the relationship between personality and ego quite fully. Furthermore, we must in this volume examine the question mainly from the point of view of the personality, rather than from that of the ego.

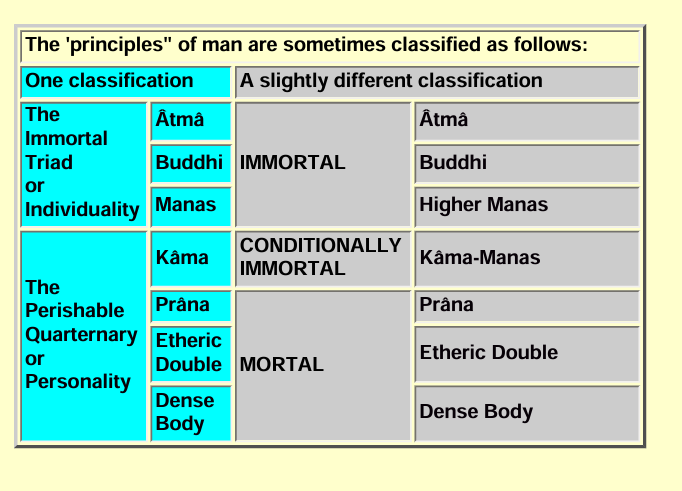

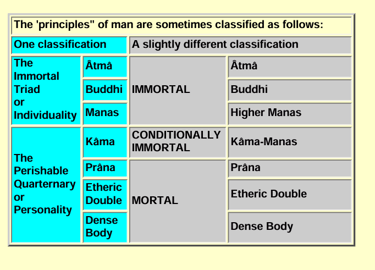

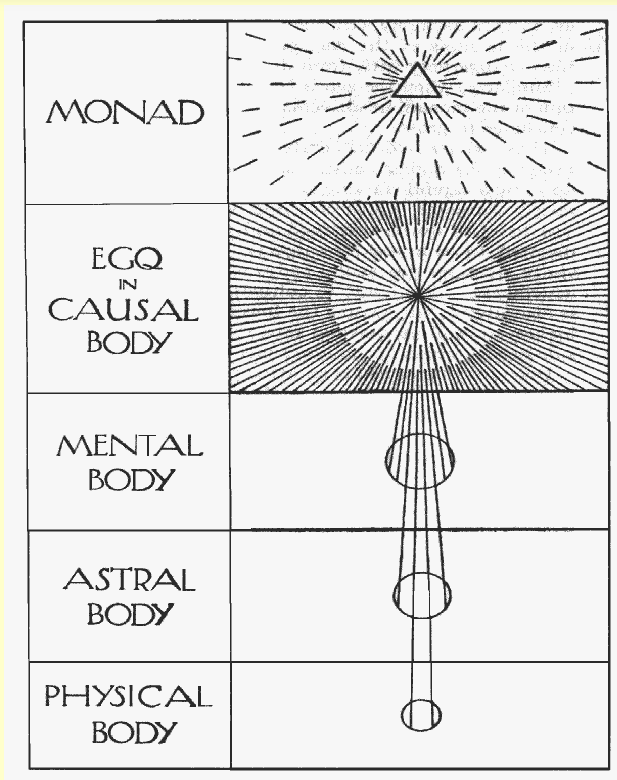

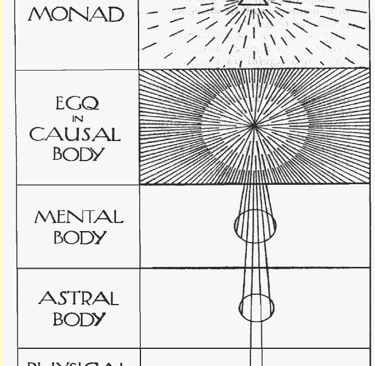

In The Causal Body we must again take up the subject, which is one of very great importance, but then, of course, principally from the point of view of the ego. The personality consists of the transitory vehicles through which the true man, the Thinker, expresses himself in the physical, astral and lower mental worlds; i.e., the physical, astral and lower mental bodies, and of all the activities connected with these vehicles. The individuality consists of the Thinker himself, the Self in the causal body. As a tree puts out leaves, to last through spring, summer and autumn, so does the individuality put out personalities to last through the life-periods spent on the physical, astral and lower mental planes.

Just as the leaves take in, assimilate, and pass on nutriment to the sap, which is eventually withdrawn into the parent trunk, and then fall and perish, so does the personality gather experience and pass it on to the parent individuality, eventually, when its task is completed, falling and perishing. The ego incarnates in a personality for the sake of acquiring definiteness. The ego on his own plane is magnificent, but vague in his magnificence, except in the case of men far advanced on the road of evolution.

A classification used by H.P. Blavatsky is as follows. She speaks of four divisions of the mind:

[1] Manas-taijasi, the resplendent or illuminated manas, which is really buddhi, or at least that state of man when his manas has become merged in buddhi, having no separate wil of its own.

[2] Manas proper, the higher manas, the abstract thinking mind.

[3] Antahkarana; the link or bridge between higher manas and kâma-manas during incarnation.

[4] Kâma-Manas, which on this theory is the personality. Sometimes she calls manas the deva-ego, or the divine as distinguished from the personal self. Higher manas is divine because it has positive thought, which is kriyashakti, the power of doing things, all work being in reality done by thought-power. The word divine comes from div to shine, and refers to the divine quality of its own life which shines from within manas.

The lower mind is merely a reflector, having no light of its own; it is something through which the light comes, or through which the sound comes –merely persona, a mask.

Among the Vedantins, or in Shri Shankarâchârya's school, the term antakarana [see p. 271] is used to indicate the mind in its fullest sense, meaning the entire internal organ or instrument between the innermost Self and the outer world, and is always described as of four parts:

[1] Ahamkâra------------The "I maker"

[2] Buddhi ----------------Insight, intuition, or pure reason

[3] Manas ----------------Thought

[4] Chitta -----------------Discrimination of objects

What the Western man usually calls his mind, with its powers of concrete and abstract thought, is the last two in the above classification, viz., Manas and Chitta. The Theosophist should recognise in the Vedantic divisions his own familiar âtmâ, buddhi, manas, and the lower mind. In the symbolism of Freemasonry, the lower mind and the mental body are represented by the S.D. The following table sets out the principles of man in the system of Freemasonry:

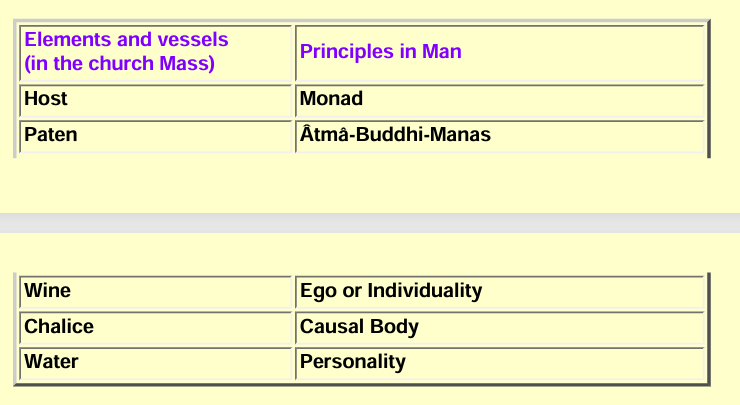

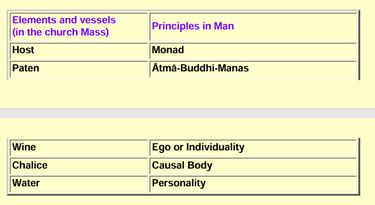

Thus the Higher Triad or Spiritual Trinity, both in God and man, are represented in Freemasonry by the three Principal Officers, while the lower self, personality, or quaternary, is represented by the three Assistant Officers and the Tyler. In Christianity we find the following symbolism:

The taking on of a personality by the ego has also been likened to the projection of a spark from the Flame of Mind. The flame fires the material upon which it has fallen, and from that a new flame will arise, identical in its essence with that which generated it, but separated for purposes of manifestation. Hence it is said that you may light a thousand candles from a single flame, but the flame is never diminished, although a thousand flames are visible where only one was visible before. The Thinker, the individuality, alone endures; he is the man for whom "the hour never strikes", the eternal youth who, as the Bhagavad Gitâ expresses it, puts on and casts off bodies as a man puts on new garments and throws off the old.

Each personality is a new part for the immortal Actor, and he treads the stage of human life over and over again; but in the life-drama each character he assumes is the child of the preceding ones, and the father of those to come, so that the life-history is a continuous one. The elements of which the personality is composed are bound together by the links of memory caused by the impressions made on the three lower vehicles, and also by the self-identification of the Thinker with his vehicles, which sets up the personal " I " consciousness known as Ahamkâra, derived from Aham meaning " I ", and kâra meaning "making"; Ahamkara thus means the " I –maker". In the lower stages of evolution, this " I " consciousness is in the physical and astral vehicles, the greatest activity being in these bodies; later it passes to the lower mental body, which then assumes predominance.

The personality, with its transient feelings, desires, passions, thoughts, thus forms a quasi-independent entity; yet all the time it draws its energies from the Thinker it enwraps. Moreover, as its qualifications, which belong to the lower worlds, are often in direct antagonism to the permanent interests of the individuality, the "Dweller in the body", conflict is set up, victory sometimes inclining to the temporary pleasure, sometimes to the permanent gain. In dealing with the personality, the obstacle to be overcome is asmitâ, the notion that "I am this", or what a Master once called "self-personality". The personality, as we have seen, develops through life into quite a definite thing, with decided physical, astral and mental form, occupation and habits. And there is no objection to that, if it be a good specimen. But if the indwelling life can be persuaded that he is that personality, he will begin to serve its interests, instead of using it merely as a tool for his spiritual purposes. Hence, in consequence of this error we find men seeking inordinate wealth, power, fame, etc.

"Self-personality" is the greatest obstacle to the use of the personality by the higher self, and so to spiritual progress. The life of a personality, of course, begins when the Thinker forms a new mental body [see Chapter XXXII] and it endures until that mental body disintegrates at the close of the period spent in devachan. The objective of the ego is to unfold his latent powers, and this he does by putting himself down into successive personalities. Men who do not understand this –and they are, of course, at the present time the great majority of humanity –look upon the personality as the real self, and consequently live for it alone, regulating their lives for what appears to be its temporary advantage.

The man, however, who understands, realises that the only important thing is the life of the ego, and that its progress is the object for which the temporary personality must be used. Thus, when he has to decide between tow possible courses of action, he does not, as most men do, consider which will bring him the greater pleasure or profit as a personality, but which will bring greater progress to him as an ego.

Experience soon teaches him that nothing which is not good for all can ever be good for him, or for anyone. Thus he learns to forget himself altogether, and to consider only what is best for humanity as a whole. Intensification of the personality, at the expense of the ego, is an error against which the student should ever be on his guard. Consider, for example, the probable result of the very commonest of failings –selfishness. This is primarily a mental attitude or condition, so that its result must be looked for in the mental realm. As it is an intensification of the personality, at the expense of the individuality, one of its results will undoubtedly be the accentuation of the lower personality, so that the selfishness tends to reproduce itself in aggravated form, and to grow steadily stronger. This, of course, is part of the general workings of karmic law, and emphasises how fatal a bar to progress is persistence in the fault of selfishness. For nature's severest penalty is always deprivation of the opportunity for progress, just as her highest reward is the offering of such opportunity.

When a man rise to a level somewhat higher than that of the ordinary man, and his principal activity becomes mental, there is danger lest he should identify himself with the mind. He should therefore strive to identify himself with the ego, and make the ego the strongest point of his consciousness, thus merging the personality in the individuality. The student should strive to realise that the mind is not the knower, but the instrument that the Knower uses to obtain knowledge. To identify the mind with the Knower is similar to identifying the chisel with the sculptor who wields it. The mind limits the Knower, who, as self-consciousness develops, finds himself hampered by it on every side. As a man may put on thick gloves and find that he thereby loses a great deal in delicacy of touch, so it is with the Knower when he puts on the mind.

The hand is within the glove, but its capacities are greatly lessened; so the Knower is present within the mind, but his powers are limited in their expression. As we saw in a previous chapter, the mental body possesses the characteristic of actually shaping a portion of itself into a likeness of the object presented to it. When it is thus modified, the man is said to know the object. What he knows, however, is not the object itself, but the image produced by the object in his own mental body. This image, moreover, for reasons which we have already discussed [see p. 56] is not a perfect reproduction of the object, but is liable to be coloured and distorted by the characteristics of the particular mind in which it is formed.

These considerations bring home to us that, in our minds or mental bodies, we do not know "things in themselves", but only the images of them which are produced in our consciousness. Meditation on these ideas will help the student to realise ever more and more fully that he himself, the true individuality, is not the personality which he, as the ego, has temporarily assumed for this one earth-life. The existence of an evil quality in the personality implies a lack of the corresponding good quality in the ego or individuality. An ego may be imperfect, but he cannot be evil; nor, in any ordinary circumstances, can evil of any kind manifest through the causal body. The mechanical reason for this has been explained previously.

Evil qualities can be expressed only in the four lower subdivisions of astral matter. These reflect their influence in the mental plane only on its four lower sub divisions; hence they cannot affect the ego at all. The only emotions that can appear in the three higher astral sub planes are good ones, such as love, sympathy and devotion. These affect the ego in the causal body, since he resides on the corresponding sub-planes of the mental world. The utmost result that is brought about in the causal body by long continued lives of a low type is a certain incapacity to receive the opposite good impression for a very considerable period afterwards, a kind of numbness or paralysis of the causal matter; an unconsciousness which resists impressions of the good of the opposite kind. The qualities which the ego develops thus cannot be other than good qualities. When they are well-defined, they show themselves in each of his numerous personalities, and consequently those personalities can never be guilty of the vices opposite to such qualities.

But where there is a gap in the ego, there is nothing inherent in the personality to check the growth of the opposite vice; and since others in the world about him already possess that vice, and since man is an imitative animal, it is quite probable that the vice will speedily manifest in him. The vice, however, as we have seen, belongs to the vehicles of the personality, not to the man inside them. In these vehicles its repetition may set up a momentum which is difficult to conquer; but if the ego bestirs himself to create in himself the opposite virtue, then the vice is cut off at its root, and can no longer exist, neither in this life nor in all the lives to come. In other words, the principle to be applied in practical life is, that to rid oneself of an evil quality in such a way that it can never reappear, is to fill the gap in the ego by developing the opposite virtue. Many modern schools of psychology and education now advocate this method rather than that attacking an evil quality in a more direct fashion. " Nerve us with constant affirmatives, " said Emerson, with great insight.

The personality is a mere fragment of the ego, the ego projecting but a minute portion of himself into the mental, astral, and physical bodies. This tiny fragment of consciousness can be seen by clairvoyants moving about within man. Sometimes it is seen as "the golden man the size of a thumb," who dwells in the heart. Others see it as a brilliant star of light . A man may keep this Star of Consciousness where he will, i.e., in any one of the seven Chakrams of the body. Which of these chakrams is most natural depends largely upon the type or "ray" of the man, and also, it seems, upon his race and sub-race. Thus men of the fifth sub-race of the Fifth Root-Race nearly always keep that consciousness in the brain, in the chakram dependent upon the pituitary body. There are however, men of other races who keep it habitually in the heart, the throat, or the solar plexus.

The Star of Consciousness is the representative of the ego in the lower planes, is in fact, what we know as the personality. But although, as we have seen, that personality is part of the ego, its only life and power being that of the ego, it nevertheless often forgets those facts and comes to regard itself as an entirely separate entity, and works for its own ends. In the case of ordinary people who have never studied these matters, the personality is to all intents and purposes the man, the ego manifesting himself only very rarely and partially. There is always a line of communication between the personality and the ego; this is called antahkarana. Most people make no effort to use this line.

In its earlier stages evolution consists in the opening up of this line of communication, so that the ego may be able increasingly to assert himself through it and finally to dominate the personality. When this is achieved, the personality has no separate thought or will, but becomes [as it should be] merely an expression of the ego on the lower planes. The hold that the ego has over his lower vehicles is only very partial, and the antahkarana may be regarded as the arm stretched out between the little piece of the ego that is awakened, and the hand that is put down.

When the two are perfectly joined, this attenuated thread ceases to exist. In Sanskrit, antahkarana means the inner organ or instrument, and its destruction would imply that the ego would no longer need an instrument, but would work directly on the personality. Thus the antahkarana, being the link between the higher and lower self, disappears when one will operates the two. It must however, be understood that the ego, belonging as he does to an altogether higher plane, can never fully express himself in the lower planes. The most that can be expected is that the personality will contain nothing which is not intended by the ego, that it will express as much of him as can be expressed in the lower world.

A man completely untrained has practically no communication with the ego; the Initiate has full communication. [ NOTE –It would appear here that, as every other "step" on the occult path, Initiation confers the possibility of full communication with the ego rather than its complete realisation; the Initiate must by his own efforts convert the possibility into an actuality. –A. E. Powell ] Between these two extremes there are, of course, men at all stages. It must be born in mind that the ego himself is in process of development, and we therefore have to deal with egos in very different stages of advancement. In any case an ego is in many ways something enormously bigger than a personality can ever be.

Although the ego himself is but a fragment of the Monad, he is yet complete as an ego in his causal body even when his powers are undeveloped; whereas in the personality there is but a touch of the life of the ego. It is obviously of great importance that the earnest student should do all in his power to make and keep active the connection between his personality and his ego. In order to do this he must pay attention to life, for the paying attention is the descent of the ego in order to look through his vehicles. Many men have fine mental bodies and good brains, but they make little use of them, because they do not pay attention to life. Thus the ego puts but little of himself down into the lower planes, and so the vehicles are left to run riot at their own will.

The cure for this, very briefly, is as follows: The ego should be given the conditions he desires; if this is done, he will promptly put himself down more fully and avail himself of the conditions offered. Thus, if he desires to develop affection, the personality must provide the opportunity for developing affection to the fullest extent on the lower planes. If he desires wisdom, then the personality must by study endeavour to make itself wise on the physical plane. Pains should be taken to find out what the ego desires; then, if the necessary conditions are provided, he will appreciate the effort and be delighted to respond. The personality will have no cause to complain of the response which the ego will make. In other words, if the personality pays attention to the ego, the ego will pay attention to the personality. The ego puts down a personality much as a fisherman makes a cast.

He does not expect that every cast will be successful, and he is not deeply troubles if one proves a failure. To look after a personality is only one of his activities, so he may very well console himself with successes in other lines of activity. In any case, failure represents the loss of a day, and he can hope to do better with another day. Often the personality would like more attention from the ego, and he may be sure he will receive it as soon as he deserves it, as soon as the ego finds it worth while.

In the Christian Church, the sacrament of Confirmation is intended to widen and strengthen the link between the ego and the personality. After the preliminary widening of this channel, the divine power rushes through the ego of the bishop into the higher manas of the candidate. At the signing of the cross, it pushes upwards into the buddhic principle, and from there into the âtmâ or spirit. The effect upon âtmâ is reflected in the etheric double, that upon the buddhi is reproduced in the astral body, and what is done to the higher manas should be similarly mirrored in the lower mind. This result is not merely temporary, for the opening up of the connections made a wider channel through which a constant flow can be kept going.

The general effect, as said, is to make it easier for the ego to act on and through his vehicles. The various vehicles of man, looked at from below, give the impression of being one above the other, although they are not, of course, really separated in space, and also of being joined by innumerable fine wires or lines of fire. Every action which works against evolution puts an unequal strain upon these, twisting and entangling them. When a man goes badly wrong in any way, the confusion between the higher and lower bodies is seriously impeded; he is no longer his real self, and only the lower side of his character is able to manifest itself fully. The Christian Church provides a method of assisting man more rapidly to regain uniformity. For one of the powers specially conferred upon a priest at ordination is that of straightening out this triangle in higher matter; this is the truth behind "absolution", the co-operation of the man having been first obtained by "confession". A break in the connection between the ego and his vehicles results in insanity. If we imagine each physical particle in the brain is to be joined to its corresponding astral particle by a small tube, each astral particle being similarly joined to its corresponding mental particle, and each mental particle to its corresponding causal particle, then so long as all these tubes are in perfect alignment there will be a clear communication between the ego and his brain. But if any of the sets of tubes be bent, closed, or knocked partially aside, it is obvious that the communication might be wholly or partially interrupted. From the occult standpoint, the insane may be divided into four main classes, as follows:

[1] Those who are insane from a defect in the physical brain. The brain may be too small, injured by some accident, pressed upon by a growth, or have its tissues softened. [2] Those whose defect is in the etheric brain, so that the etheric particles do not correspond with the denser physical particles. [3] Those in whom the astral body is defective, the tubes being out of alignment with either the etheric or mental particles. [4] Those in whom the mental body is out of order.

Classes [1] and [2] are quite sane when out of the body in sleep, and of course after death. Class [3] do not recover sanity until the heaven-world is reached. Class [4] do not become sane until the causal body is reached, so that for this class the incarnation is a failure. More than 90 percent of the insane belong to classes [1] and [2]. Obsession is caused by the ousting of the ego by some other entity. Only an ego who had a weak hold on his vehicles would permit obsession. Although the hold of the ego upon his vehicles is less strong in childhood, yet adults are more likely to be obsessed than children, because the adult is far more likely to have in him qualities which attract undesirable entities and make obsession easy.

Briefly, the best way to prevent obsession is by the use of the will. If the lawful possessor of the body will confidently assert himself and use his will-power, no obsession can take place. When obsession occurs, it is almost always because the victim has in the first place voluntarily yielded himself to the invading influence, and his first step, therefore, is to reverse the act of submission and determine strongly to resume control over his own property. The relationship between the personality and the ego is so important that we may perhaps be pardoned for a little repetition, or recapitulation. A study of the inner vehicles of man should at least help us to understand that it is the higher presentation which is the real man, not the aggregation of physical matter in the midst of it, to which men are apt to attach such undue importance. The divine trinity within we may not yet see; but we can at least attain some idea of the causal body, which is perhaps the nearest to a conception of the true man as sight at the higher mental level can give us.

Looking at the man from the lower mental level, we can see only so much of him as can be expressed in his mental body; on the astral level we find that an additional veil has descended, whilst on the physical plane there is yet another barrier, so that the true man is more effectively hidden than ever. Such knowledge should lead us to form a somewhat higher opinion of our fellows, since we realise that they are so much more than they seem to the physical eye. In the background, there is always the higher possibility, and often an appeal to the better nature will arouse it from latency and bring it down into manifestation where we can see it. Having thus studied man as he is, it becomes easier for us to pierce through the dense physical veil and image the reality which is behind. That which is behind all men is the divine nature; hence, grasping this principle, we should be able so to modify and readjust our attitude that we are able to help other men better than we could do without this knowledge.

We have already seen, in the chapter on Contemplation, that the consciousness of the ego may be reached by maintaining the mind in an attitude of attention, without the attention being directed to anything, the lower mind being stilled in order that consciousness of the higher mind may be experienced. By this means, ideas from the ego flash down into the lower mind with dazzling light, these being the inspirations of genius. "Behold in every manifestation of genius, when combined with virtue, the undeniable presence of the celestial exile, the divine Ego whose jailor thou art, O man of matter". Genius is thus the momentary grasping of the brain by the larger consciousness of the ego, who is the real man; it is the putting down of the larger consciousness into an organism capable of vibrating in answer to its thrills.

Flashes of genius are the voice of the living Spirit in man; they are the voice of the inner God, speaking in the body of man. The phenomena included in the term "conscience" appear to be of two distinct kinds. Conscience is sometimes used to describe the voice of the ego, and at other times it is spoken of as the will in the domain of morality. Where it is the voice of the ego it should be recognised that it is not always infallible, but may often decide wrongly. For the ego cannot speak with certainty on problems with which it is unfamiliar, being dependent upon experience before he can judge correctly. That form of conscience, however, which comes from the will does not ell us what to do, but rather commands us to follow that which we already know to be best, usually when the mind is trying to invent some excuse to do otherwise. It speaks with the authority of the spiritual will, determining our path in life.

But the will, which is undoubtedly a quality of the ego, must not be confused with the desires of the personality in the lower vehicles. Desire is the outgoing energy of the Thinker, determined in direction by the attraction of external objects; will is the outgoing energy of the thinker, determined in direction by conclusions drawn by reason from past experiences, or by the direct intuition of the Thinker himself. In other words: desire is guided from without; will from within.

In the early stages of evolution desire has complete sovereignty, and hurries a man hither and thither; the man is ruled by his astral body; in the middle stages of evolution there is continual conflict between desire and will; the man struggles with kâma-manas; in the later stages of evolution desire dies, and will rules unopposed; the ego is in command.

Summarising, we may say that the voice of the ego or higher self speaking [1] from âtmâ, is true conscience; [2] from buddhi, is intuitive knowledge between right and wrong; [3] from higher manas, is inspiration; when inspiration becomes continuous enough to be normal, it is genius. As was briefly mentioned in Chapter VI, genius which is of the ego, sees instead of arguing; true intuition is one of its faculties, as reason is the method of the lower mind.

Intuition is simply insight; it may be described as the exercise of the eyes of the intelligence, the unerring recognition of a truth presented on the mental plane. It sees with certainty; but no reasoned proof of its certitude can be had, because it is beyond and above reason. But before the voice of the ego, speaking through intuition, can be recognised with certainty, careful and prolonged self training are necessary. It would appear, however, that the word intuition is used with significations that vary somewhat. Thus it has also been said that the attainment of reliable intuition in daily life means the opening of a direct channel between the buddhic and the astral bodies. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that it works rather through the heart-centre or chakram, than through the mind. The consecration of a bishop has special reference to this centre and to the stimulation of the intuition. We thus distinguish two distinct modes for the transmission of "intuition" from the higher to the lower consciousness. The one comes from the higher to the lower mental plane, the other direct from the buddhi to the astral body.

The intuition of the causal body has been described as the intuition which recognises the outer; that which comes from buddhi is intuition which recognises the inner. With buddhic intuition, one sees things from inside; with intellectual intuition, one recognises something outside oneself. Which of these lines is the easier depends upon the method of individualisation. Those who individualised through deep understanding will receive their intuition as a conviction, requiring no reasoning to establish its truth at present, though it must have been understood in previous lives or out of the body in the lower mental plane.

Those who attained individualisation through a rush of devotion, will receive their intuition from the buddhic plane to the astral body. In both cases, of course, the condition of receptivity to intuition is a steadiness of the lower vehicles. We need not shrink from the fact that there is frequently a psychological instability associated with genius, as expressed in the saying that madness is akin to genius, and in the statement of Lombroso and others that many of the saints were neuropaths. Very often the saint and the visionary may have overstrained their brains, so that the physical mechanism is distorted and rendered unstable. Furthermore, it is sometimes true that the instability is the condition of the inspiration.

As Professor William James has said: "If there were such a thing as inspiration from a higher realm, it might well be that the neurotic temperament would furnish the chief condition of the requisite receptivity" [Varieties of Religious Experience, p. 19]. Genius may thus have an unstable brain because the higher consciousness is pressing upon it in order to improve the mechanism; so the brain is kept in a state of tension, and under such circumstances it may easily go too far until the structure breaks down under the strain. But the abnormality is on the right, not on the wrong side, being on the very front of the crest of human evolution. It is the instability of growth, not of disease. An attempt to stimulate the heart-centre is also made in the Christian Church at the time of the reading of the Gospel, the sign of the cross being made by the thumb over the heart-centre, as well as over those between the eyebrows and the throat.

This use of the thumb corresponds to a pugnal pass in mesmerism, and seems to be employed when a small but powerful stream of force is required, as for the opening of centres. The heart is the centre in the body for the higher triad, âtmâ-buddhi-manas. The head is the seat of the psycho intellectual man, its various functions being in seven cavities, including the pituitary body and the pineal gland. A man who can take his consciousness from the brain to the heart should be able to unite kâma-manas to higher manas, through lower manas, which, when pure, is the antahkarana; he will then be in a position to catch some of the promptings of the higher triad. In the Indian methods of Yoga, steps are taken to prevent the dangers of hysteria in those who are coming into touch with the higher planes, insistence being made upon discipline and purification of the body, and control and training of the mind.

The ego frequently puts ideas into the lower consciousness in the form of symbols; each ego has his own system of symbols, though some forms seem general in dreams. Thus for example, it is said that to dream of water signifies trouble of some sort. Now while there may be no real connection between water and troubles, yet if the ego knew that the personality held that particular belief with regard to water, he might very likely choose such a form of symbolism in order to warn the personality of some impending misfortune. In some cases the ego may manifest himself in a curious external way.

Thus, for example, Dr. Annie Besant has said that while she is speaking one sentence of a lecture she habitually sees the next sentence actually materialise in the air before her, in three different forms, from which she consciously selects that one which she thinks best. This must be the work of the ego, though it is a little difficult to understand why he takes this particular method of communication instead of impressing his ideas direct on the physical brain. The relationship between the personality and the ego is graphically described in The Voice of The Silence: "Have perseverance as one who doth for evermore endure. Thy shadows [ie., personalities] live and vanish; that which in thee shall live forever, that which in thee knows, for it is knowledge, is not of fleeting fleeting life; it is the man that was, and will be, for whom the hour shall never strike."

A vivid description of the ego is given also by H. P. Blavatsky in The Key To Theosophy : "try to imagine a ‘Spirit', a celestial being, whether we call it by one name or another, divine in its essential nature, yet not pure enough to be one with the ALL, and having, in order to achieve this, so to purify its nature as finally to gain that goal. It can do so only by passing, individually and personally, i.e., spiritually and physically, through every experience and feeling that exists in the manifold or differentiated universe. It has, therefore, after having gained such experience in the lower kingdoms, and having ascended higher and still higher with every rung of the ladder of being, to pass through every experience on the human planes.