THE RANKS!

THE RANKS!. They also record My proclamations to the universe, And send down the sūras from the “Book,” little by little. From these sevens emerge precisely “Twenty-Eight Saints”; These are the ones who “breathe spirit” and grant My-consciousness!

APOCALYPSE BOOK

THE RANKS

For a moment, the hidden eye within my heart opened and remained,

And my essence spoke thus on behalf of my being:

“The verse that says, ‘Allah raises degrees’—

It is the secret of you and me, and profoundly deep!

I am not an empty essence; I am filled with Myself—

That is, My creations are the family within Me.

Creation is not addition, but division! Why?

Because within the Infinite no other operation can be.

All My works are the distribution of the beings within Me;

Every Name you awaken in the heart is My reflection!

Through these Names I rule over all things,

And for this reason I call Myself ‘Rabb al-‘Alamīn’!

That is, each of My Names is itself an entire realm;

These exalted saints are My bodiless body.

Each of them is a pupil-point that beholds Me;

Freed from matter, and in their being, non-being.

From among them, first the initial seven awaken;

Clothing themselves in the purest substance, dyed in My form.

These first “Seven Saints” are the “Seven-Class Army”!

From each of them, the essence of a servant has become fluid.

One who ascends in Mi‘rāj beholds the Lord from whom his essence emerged;

He does not deny his mother and father as his own children.

Yet solely in gratitude he must prostrate;

He must not call that state “Allah,” even in ecstasy!

The first seven awaken the second sevens;

“It is the final boundary!”—only the soul may pass beyond.

Four among them record what everyone does;

Surely they will stand as witnesses in the Supreme Tribunal!

They also record My proclamations to the universe,

And send down the sūras from the “Book,” little by little.

From these sevens emerge precisely “Twenty-Eight Saints”;

These are the ones who “breathe spirit” and grant My-consciousness!

Since one possesses the Name “Allah knows all things,”

If the Unseen belongs to Allah alone—can it be said that Adam does not know?

Had this Adam not been granted the primordial nature by the Lord,

Man would remain like a pure angel or an animal!

In every human, this natural essence of Mine is concealed;

What turns him away from this qiblah is his own reason!

The angels that emerge from the Twenty-Eight,

Clothe the human in a simple, transparent garment.

These angels ultimately awaken the jinn;

“The verse says: Ifrit, Iblis, and Shaytan have bodily forms.”

Their souls are of fire, air, water, or earth;

They have neither consciousness nor emotion!

They execute the command given by the “Four Ifrits”;

Ruling your cell, they say: “Reap what you have sown!”

For in your cells dwells the home of every jinn;

Testing or forming the body is its task.

“We are those who stand rank upon rank in the presence of Rahman!”

You too enter the exalted line—purify your heart!

Master M.H. Ulug Kizilkecili

Türkiye/İzmir - 14 October 1998

IMPORTANT NOTE :The original text is poetic, and the author cannot be held responsible for any errors in the English translation! To read the original Turkish text, click HERE! The following section is not the author's work, and the author cannot be held responsible for any errors made!

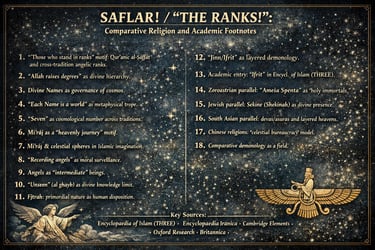

English Footnotes (Comparative / Academic)

“Those who stand in ranks” motif. The Qur’anic oath “By those ranged in ranks” (al-Ṣāffāt) is classically tied to angelic ordering and liturgical formation; modern reference works summarize angelic “ranks” as a widespread religious strategy for mapping the sacred into ordered hierarchies.

“Allah raises degrees / ranks.” The idea that Allah raises believers/learned persons in “degrees” (darajāt) underwrites a cosmology of graded proximity and authority; it is one of the Qur’anic bases for later “merit–rank” idioms in ethics, spirituality, and cosmological imagination.

Divine names as governance (Names → rule). The poem’s “Names govern everything” resonates with broader monotheist patterns where ineffable divinity is approached through mediating concepts (attributes, names, agencies). For a recent analytic treatment of how angelology mediates monotheist transcendence, see Angels and Monotheism (Cambridge Elements).

“Each Name is a world” as a metaphysical trope. The “world-per-name” move is best read as mystical-metaphysical poetics rather than standard dogmatic description; philosophically, it echoes the broader “metaphysics of being” tradition in Islam where reality is analyzed via structured intelligibility (not identical to, but comparable in method to, philosophical metaphysics).

“Seven” as a cosmological grammar. Across many cultures, “seven” operates as an organizing number for cosmic layering (e.g., “seven heavens”), sometimes in literalist, sometimes in symbolic registers; modern scholarship continues to document both modes of interpretation within Islamic cosmology.

Miʿrāj (ascension) as a comparative “heavenly journey.” In Islam, Miʿrāj is a paradigmatic ascent narrative; it also belongs to a wider Eurasian family of “heavenly journeys” used to legitimate revelation, authority, and cosmological knowledge. Britannica’s overview is a reliable starting reference.

Miʿrāj and the “celestial spheres” imagination. The Miʿrāj tradition is historically “malleable” in text and image; art-historical and literary scholarship shows how it becomes a generative template for mapping the heavens and their inhabitants.

Miʿrāj in Iranianate scholarship / terminology. Encyclopaedia Iranica’s entry on meʿrāj documents the term’s philology (“instrument of ascension”) and contextual usage, supporting a careful academic distinction between word-history and later narrative elaborations.

“Recording angels” (Kirāman Kātibīn) and moral surveillance. The poem’s “four record” motif intersects with the Qur’anic and post-Qur’anic discourse on angels who record deeds; reference literature often treats this as part of a broader “administration of judgment” constellation.

Angels as “intermediate worlds.” Comparative scholarship emphasizes angels as a middle register between transcendence and the human world, including in popular religion; this supports reading the poem’s angelic “offices” as a recognizable cross-tradition pattern, even when the poem’s specific numbers differ.

“Unseen” (al-ghayb) as a boundary category. The poem’s tension—“only Allah knows the unseen” vs. human access—matches a major theological boundary issue: how revelation, inspiration, and legitimate knowledge are delimited. (For a general cross-tradition framing of mediating beings/knowledge, see Britannica’s synthesis on angels/demons as mediators.)

Fiṭrah (primordial disposition) and anthropology. The poem’s “natural essence” tracks the Qur’anic idea of a created human orientation; academically, fiṭrah is discussed as a key hinge between ethics, theology, and the psychology of religion in Islamic thought.

Jinn/Ifrit as a graded demonology rather than one uniform “demon.” The poem’s “ifrit, Iblīs, shayṭān have bodies” belongs to a layered demonological lexicon. Britannica’s ifrit entry highlights definitional instability in early sources and later folkloric specification.

Ifrit in modern Islamic Studies reference work. For a high-grade scholarly treatment, the Encyclopaedia of Islam (THREE) entry (accessible via ISAM mirror) provides a research-level overview and bibliographic anchoring for “ʿIfrīt” usage and meanings.

Zoroastrian parallel: the “holy/bounteous immortals.” The poem’s “first seven awaken” can be compared (as a structural analogy, not an identity claim) to Zoroastrianism’s Ameša Spenta complex—beneficent divinities/archangel-like figures tied to creation and governance. Encyclopaedia Iranica is a gold-standard reference.

Zoroastrian parallel in general reference. Britannica’s amesha spenta overview reinforces the “governance of creation” framing and the archangel-like ministerial pattern.

Jewish parallel: Sekine (Shekinah) as “divine presence.” If you use the term Sekine (Shekinah) in your wider system, the closest comparative anchor is Jewish theology’s Shekhinah—God’s “dwelling/presence” immanent among people—especially as developed in Targums and rabbinic literature.

Why “presence” language matters cross-traditionally. “Presence” terms (Shekhinah, glory, indwelling) often arise to speak of immanence without collapsing transcendence—useful for framing the poem’s “heart-eye” epiphany as a recognizable mystical form.

South Asian parallel: devas/asuras and graded heavens. In Hindu traditions, devas are celestial beings and cosmology often uses tiered realms; Buddhism similarly articulates layered “planes” and higher celestial abodes. These provide a comparative vocabulary for the poem’s “classes/armies/ranks,” without asserting doctrinal equivalence.

Chinese religions: “celestial bureaucracy.” The poem’s “recording, proclamation, offices” can be fruitfully compared with the well-studied Chinese pattern of modeling the spirit world as an administrative order (officials, registers, jurisdiction), discussed in Oxford Research Encyclopedia treatments of Chinese religion.

Comparative demonology as a field (method note). Modern scholarship on demons in early Judaism/Christianity emphasizes that “demon” is a cross-cultural category with shifting boundaries; this supports reading “ifrit/Iblīs/shayṭān” as a historically textured taxonomy rather than a single stable essence.